July 1, 2015

Chicano Art, Imagery of Social Movements and José Guadalupe Posada

Written by Jim Nikas

Organizations of Mexican – Americans involving social movements have been active for many decades. In fact the roots of such organizations as they relate to Mexican influence and history extend well beyond the formation of the United States. But where Mexican artist/engraver José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913) is concerned there is a perception that he was a champion of human rights and that the imagery he created supported a revolutionary perspective. Not unexpectedly this understanding of Posada's role has inspired artists in many artist collectives dedicated to producing art to effect social change. The Taller de Grafica Popular (Mexico City); the ASARO (Asambleadelos Artistas Revolucionarios de Oaxaca, Mexico), Consejo Grafico, The Royal Chicano Airforce (both United States); and collectively the Chicano Art movement (United States) are but a few examples.

However, this interpretation of Posada as a revolutionary is not supported by study of his catalogue raisonné. Yet when considering the collective spirit of his labor combined with his re-discovery and re-purposing of his work in post-revolution Mexico (Figure 1) and decades later in the United States, a very different picture emerges. It gives us a revolutionary Posada and an artist of the people whose imagery is very much a part of artistic expression in today’s social movements and a significant part of the art represented in the Chicano Movement.

In tracing the history of Posada’s reputation as a revolutionary and artist of the people it is necessary to examine a variety of interconnecting elements of Mexico’s post-revolution period in the 1920’s and 1930s while at the same time giving consideration to certain global events that contributed significant foundational components to Posada’s legacy.

The following numerical listing attempts to place chronological events and interconnections into context, it might be likened to a "connect the dots" exercise because it is only by re-constructing the various events over time with their interconnections in this way that the origin of Posada's influence emerges.

1) Initially and perhaps most important was Posada’s main publisher, Antonio Vanegas Arroyo (b. Puebla 1852 – d. Mexico City 1917). Their relationship spanned approximately twenty-two years. Due to the success and continuity enjoyed by the Mexico City based Vanegas Arroyo printing house, a large body of Posada’s work continued to be seen well after the death of Posada in 1913.

2) Printing house founder Antonio Vanegas Arroyo passed away in 1917. In the years that followed, Antonio’s widow Carmen Rubi, brother Blas, Antonio’s son Blas and lastly grandson Arsacio all contributed to running the business of the printing house. Eventually, Arsacio was left solely in charge. He promoted the legacy of Posada by organizing exhibitions and by continuing to issue publications and editions of prints utilizing the printing blocks that his grandfather had commissioned from Posada. From this perspective there was a clear advantage to promoting Posada for the Vanegas Arroyo family as it was good for business.

But is was not just business, Arsacio would later help support the Castro brothers in the late 1950s as they planned the Cuban Revolution; this revolutionary association certainly did not distract from the spirit of Posada as it reflected a very dynamic activism regarding social movements. It may have extended back to his grandfather's interests in Cuban music or perhaps his grandfather's interest in Cuban Independence from Spain. Nevertheless, two additional key elements combined to pave the way for Arsacio's continued effort to develop business and to promote Posada's legacy.

3) The first element begins in 1920-21 at the end of the Mexican Revolution. At that time Mexico was beginning to recover from the devastating affects of the Revolution and into that period stepped a number of leaders and artists who helped form what would become the new vision and identity of Mexico. General Alvaro Obregon (1880-1928) was president (1920-1924) and he named José Vasconcelos (1882-1959) as Rector of the National University of Mexico (1920-21) and later as Minister of Education (1921-24). President Obregon and Vascocelos saw the need for improvement in the educational system within Mexico. Accordingly, Vasconcelos oversaw the construction of ultimately thousands of schools and libraries throughout Mexico. At the same time, to foster a sense of national pride and identity, support was given to development of the arts, ultimately proving foundational to the muralist movement thus helping support the work of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, David Siqueros and Jean Charlot among others.

It is during this time that the first significant mention of Posada is made. This first note is in the catalogue text of the 1921-22 publication(s) Arte Populares de Mexico by Gerardo Murillo (aka Dr. Atl). The publication was a review of Mexican art including ceramics, textiles and plastic arts. The publication accompanied a major exhibition of Mexican folk art organized and designed to showcase and promote things Mexican. The exhibition was shown first in Mexico and then in Los Angeles in 1922. The text written by Dr. Atl mentions engraver Guadalupe Posadas, spelling his name incorrectly with an "s" and includes some examples of his prints, but no more.

4) The second key element referred to above is the first significant writing about Posada. It is made by French-Mexican artist Jean Charlot who first encounters Posada's work in 1920 while exploring little shops in Mexico City's Zocolo behind the main Cathedral. Five years later he writes a small article in one of Mexico City's weeklies Revista de Revistas. The article is entitled “Un Precursor del Movimiento del Arte Moderno, El Grabador Posadas,” and again Posada's name is misspelled.

Yet Jean Charlot does more than just write an article about Posada. He begins to promote Posada. Over fifty years later, in a 1978 interview with Ron Tyler and Peter Morse, Charlot describes showing a printing block to Diego Rivera (in the 1920s) and although Rivera is aware of Posada, it is the first time he has seen one of the printing blocks. Rivera eventually promotes Posada through his art and in written word. At the time of introduction to Rivera, Charlot is making frescos just as Rivera and other muralists including José Clemente Orozco (who later writes of Posada as inspiring his art). Most significantly here is the relationship that Charlot and Rivera have with the publisher of a new periodical Mexican Folkways, Frances Toor.

5) In 1925, Frances Toor started Mexican Folkways as a bilingual periodical communicating within its editions: "art, music, archaeology, and the Indian himself as part of the new social trends, thus presenting him as a complete human being." There were many contributors to the periodical including: Jean Charlot, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and Anita Brenner. Charlot and Rivera both served as artistic directors.

In 1928, an edition was dedicated exclusively to the work of José Guadalupe Posada. The edition is written by Toor and in it she describes Posada as, "the greatest artist produced by the Revolution.” and in referring to Posada's relationship to the Porfirio Diaz presidency and first years of the Mexican Revolution she writes, "his engravings crystallize all the stirring events of those days: ---the inevitable struggle of the middle class against feudalism and the reaction of the masses to politics, sports, miracles, crime, the parasitic church and budding imperialism." But this is just a teaser, she announces that a monograph of Posada's work is to be published shortly with "five hundred cuts" loaned by Blas Vanegas Arroyo. In the meantime, an article praising Posada, written by Anita Brenner appears in the periodical in The Arts in July of 1928. The article is entitled, A Mexican Prophet. The article is an excerpt from her book Idols Behind Altars which is released in 1929. Again, Posada is lauded as champion of the underclass and artist of the people.

Then in 1930, as promised, the monograph on Posada is published. It lists Frances Toor, Blas Vanegas Arroyo and Pablo O'Higgins as the editors with a forward by Diego Rivera. The key players have now been identified and Posada is on his way to fame some seventeen years after his death.

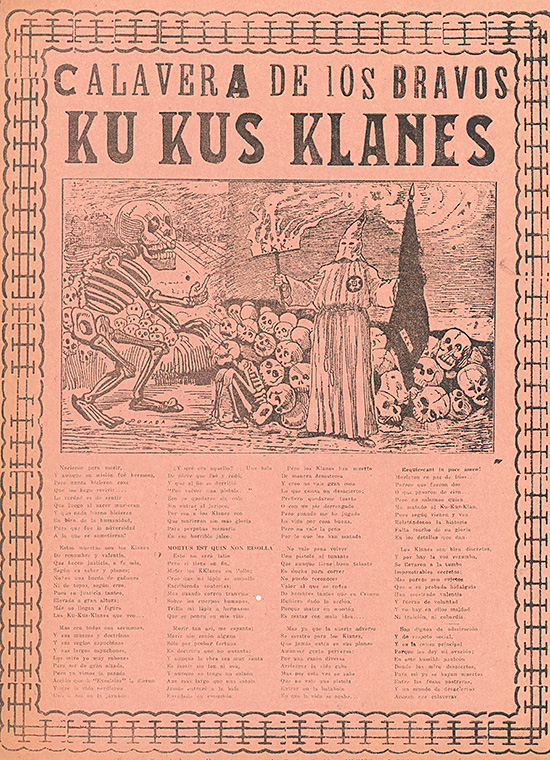

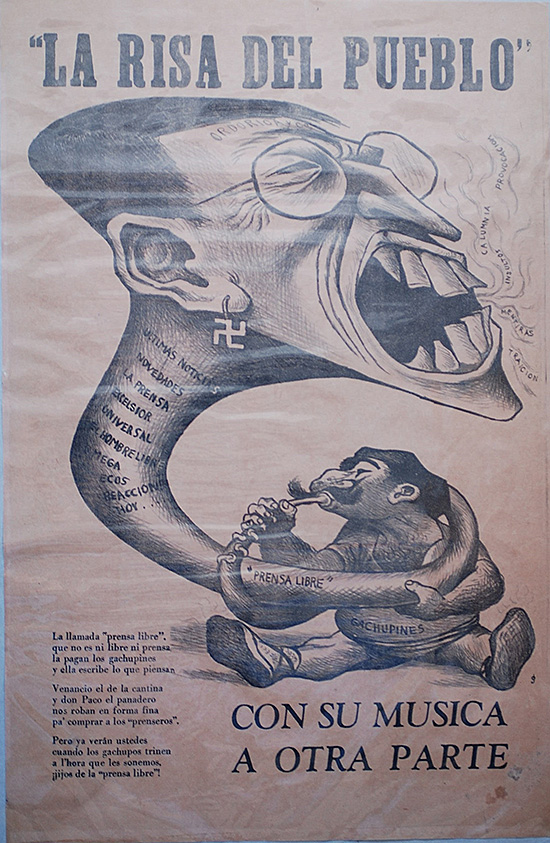

6) In response to the needs of the times the Taller de Grafica (Peoples' Workshop) forms in Mexico City in 1937. Its founders are Pablo O’Higgins, Leopoldo Mendez and Luis Arenal. Its members believed that art could be used to influence social causes. Some of the Taller de Grafica members were revolutionary, many were members of the Communist Party but regardless they had political agendas, with their focus centering around producing art that communicated the sentiments of anti-war, pro-labor, anti-corruption and in the 1940s anti-Nazi/fascist themes (Figure 2)

Co-founder Pablo O'Higgins was originally from the United States and came to Mexico in 1922. Like many ex-Patriots, Edward Weston, Frances Toor and Tina Modotti to name a few, O'Higgins began to build associations. One was with Diego Rivera and many of the artists working in Mexico City in the post-revolution time of the 1920s and 1930s. As was somewhat popular at the time, he joined the Communist party and won a scholarship to study at the Academy of Art in the Soviet Union. His past association with the work of Posada (O'Higgins had pulled the prints for the Posada Monograph that Frances Toor had published) together with his political beliefs, influenced his work. Other artists, many from Europe and the United States that worked at the Taller de Grafica shared similar views. As they traveled, taught and exhibited their influence spread.

Moving through the 1940s and into the 1960s the social elements contained in the imagery of the work and the influence of the Taller de Grafica ran parallel with and reflected cultural changes and events especially as they related to Civil Rights Movements. Within the United States movements addressing the inequality between people of color and the white population were progressing. President Truman had integrated the military, Japanese Americans had distinguished themselves fighting in WWII, increasing protests and demonstrations in the Southern US were drawing more and more attention to the plague of racism, as evidenced by segregation in the South and rampant discrimination.

Beginning in the 1940s a guest-worker program between the United States and Mexico brought millions of agricultural workers (called Braceros) from Mexico into the United States. The program was supposed to temporarily shore-up labor shortages caused by the drafting of personnel needed for services in WWII. Many of the workers remained in the United States, some legally and some illegally. By the time the guest-worker program ended in 1964 the population of Mexican Americans (as included in the category of Hispanics) had doubled from 1.5% to over 3% of the population in the United States.

Historically, in parts of the United States that had once been under Spanish and Mexican and authority there was already a strong Mexican presence but thanks to the labor needs brought on by WWII, the population of Mexican people began to disperse more and more. Numbers of Mexican or Hispanic origin people swelled from 2 million in 1940 over 9 million by 1970. (Note: Today one in every six Americans are of Hispanic origin, with 63% of Mexican origin.)

As Civil Rights Movements achieved more and more success in the 1960s the term Chicano gained usage in many campuses and cities containing populations of Mexican-Americans. Chicano civil rights activists, within the Mexican-American communities of the United States organized to end discrimination, improve farmworking conditions, protest war (particularly the Vietnam War), secure voting rights and ultimately define an ethnic identity drawing upon their roots of origin in Mexico as well as their common experiences in the United States. In that search and activism the Chicano Movement (also called El Movimiento) evolved.

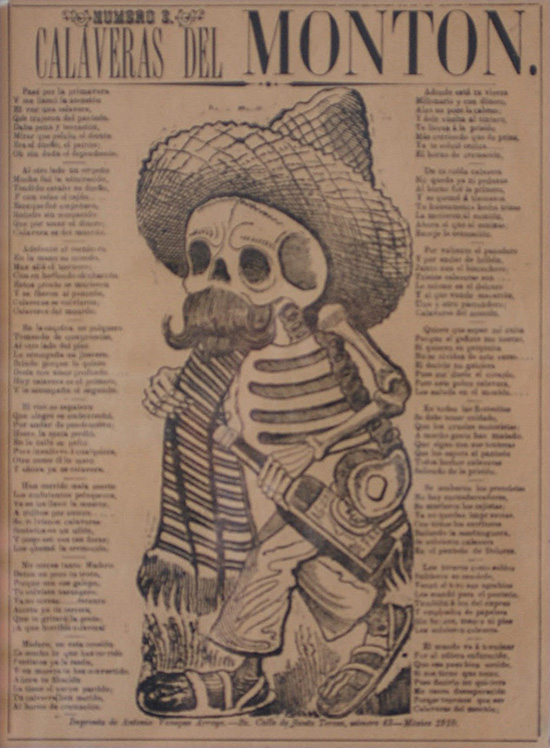

Chicano artists looking to find reference for ethnic identity could look to the work of the Mexican muralists for the larger statements but for the posters, flyers and myriad other printed works, the Taller de Grafica and the imagery and inspiration of Posada's myth was a perfect match. In his work José Guadalupe Posada represented thousands of popular images capturing and recording much of Mexico’s culture. It likely helped that Posada was of the working class with indigenous ancestry. By now Posada was seen as the artist of the people, a revolutionary who fought the dictator Porfirio Diaz and crusaded supporting the Mexican Revolution. Neither of these last two items are strictly true, as Posada also made political cartoons of Diaz's opposition (Figure 3) and with his death in January of 1913 Posada only lived more or less to see the first eighteen months of the Mexican Revolution.

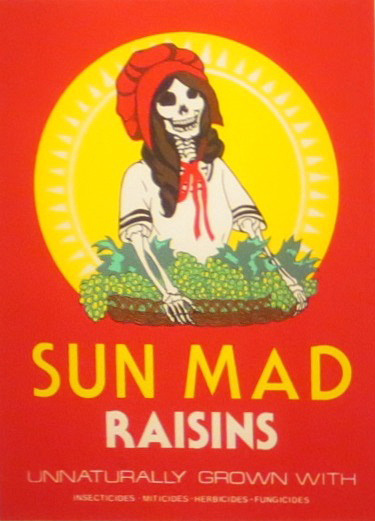

Further, Posada's most popular images were of skeletons (calaveras) ordinarily seen during observance of the Day of the Dead (November 2). Calaveras had their origins in the pre-Columbian culture of Mexico but Posada and his editor Vanegas Arroyo used them to communicate many editorial messages. Lastly, Posada's work had also been supported and evolved through the Taller de Grafica. In these rudiments the Chicano Art Movement found an inspiring and influential spirit.

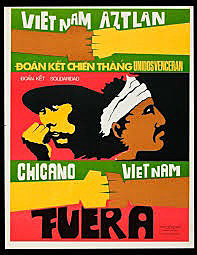

Motifs in Chicano Art draw upon the Mexican American experience in the United States. For example, a reference to Aztlán often appears. When used in the context of the Chicano Movement it refers to the lands of Northern Mexico that were taken by the United States under the Treaty of Guadalupe after the Mexican-American War in 1848; but Aztlán has its roots as the place of origin for pre-Columbian Mexican civilization. It became symbolic for many people in El Movimiento and may be seen as a symbol or reference in a variety of artistic renderings (Figure 4)

Chicano artists incorporate images from Mesoamerica, the Mexican Revolution, religious icons such as the saints and patron saint of Mexico Our Lady of Guadalupe and the images of everyday life.

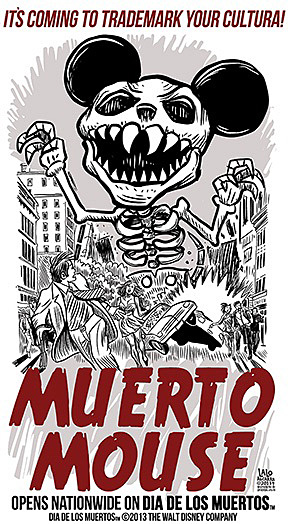

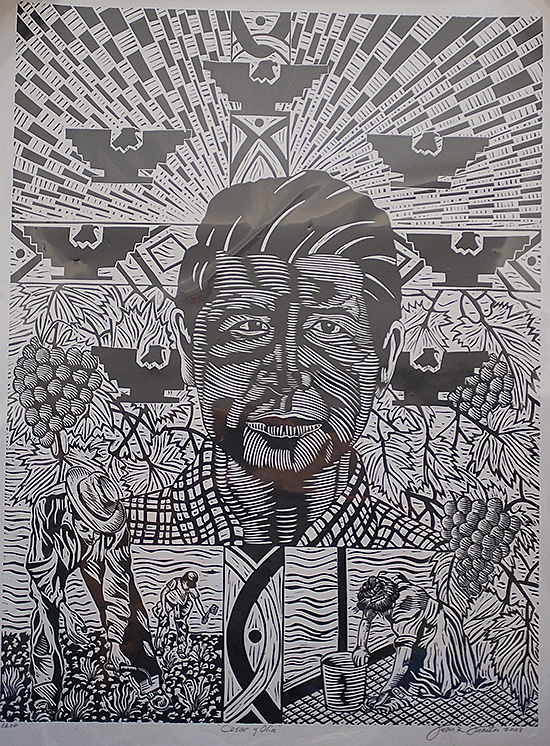

The art reflects the experience at all levels from the unique perspective of the times past and present. Whether it is an image demanding immigration reform, social commentary (Figure 5) an end to discrimination, crying for peace, fighting drug cartels, exposing corruption, supporting the United Farm Workers (Figure 6

and Figure 7

) or remembering the dead or life of someone as a calavera for Day of the Dead, the roots extend deeply into Posada's legacy.

In the end José Guadalupe Posada's contribution to the art of social movements and in particular Chicano Art, whether he himself was a revolutionary or not matters little, his inspiration and influence are undeniable.

Jim Nikas is a founder, curator and co-owner of The Brady Nikas Collection (formerly The New World Prints Collection). Privately held, the collection houses one of the largest collections of works by José Guadalupe Posada and Manual Manilla in the United States. Nikas has curated a number of exhibitions in Mexico and the US and has lectured widely on the subject of Mexican printmaking, and most predominantly on the life, work and legacy of José Guadalupe Posada. Jim Nikas also co-produced and wrote the screenplay for a documentary film about Posada, entitled Art and Revolutions (for more information, visit www.posada-art-foundation.com). He is a former director of the Coro Hispano de San Francisco and also a member ofthe Advisory Board of the Documentary Film Institute Board at San Francisco State University.

[i] See Posada's Resurrection in www.posada-art-foundation.com.

[ii] Figure 1 Broadside published in 1924 by Blas Vanegas Arroyo combining an original image by Posada and an image of a Ku Kus Klansman by an unknown artist.

[iii] Bonilla Reyna, Helia Emma. José Guadalupe Posada a 100 años de su partida. México, ICA-BANAMEX-Íconos de Siempre, 2012.

[iv] Dr. Atl, (Gerardo Murillo) Las Artes Populares en México, 2 vols. (1921; Mexico: Editorial Cultura, 1922).

[v] Charlot, Jean. Un precursor del movimiento de Arte Mexicano. Revista de revistas, August, 1925.

[vi] Interview of Jean Charlot by Ron Tyler and Peter Morse, Ron Tyler of the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art in conjunction with his exhibition of José Guadalupe Posada and its catalog, 1978, Ron Tyler, ed., Posada’s Mexico (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress in cooperation with the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, 1979).

[vii] Stern, Peter A., Frances Toor and the Mexican Cultural Renaissance, From the Selected Works of Peter A. Stern, University of Massachusetts - Amherst, January 2000.

[viii] Frances Toor, Guadalupe Posada, Mexican Folkways, v.4, no.3 (July-September, 1928).

[ix] Brenner, Anita. Idols Behind Altars. New York: Biblo and Tannem, 1967. Originally published in 1929.

[x] Toor, Frances, Paul O'Higgins and Blas Vanegas Arroyo. Monografía: las obras de José Guadalupe Posada, grabador mexicano. Mexico City: Mexican Folkways, 1930.

[xi] Figure 2 José Chavez Morado 1909-2002 lithograph (1939) La risa del pueblo con su musica a otra parte, published by the Taller de Grafica Popular.

[xii] Gratton, Brian; Gutmann, Myron (January 2006) [2006], Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition 1 (First Edition ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–177 to 1–179.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Figure 3 Calaveras del Monton, by Posada, a 1910 broadside published by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, shows a caricature poking fun of Francisco Madero who ran in opposition to Porfirio Diaz.

[xv] Figure 4 Chicano artist Malaquis Montoya's 1972 poster protesting the Viet Nam war and drawing attention to the disproportionate number of Chicanos killed and wounded, www.malaquiasmontoya.com.

[xvi] Figure 5 Chicano artist Lalo Alcaraz's 2013 social commentary cartoon poking fun at the Disney-Pixar attempt to trademark the religious observance of Dia de los Muertos, www.laloalcaraz.com.

[xvii] Figure 6 Chicano artist Juan Fuentes' 2012 image entitled Cesar y Olin of United Farm Workers founder/unionizer Cesar Chavez, www.juanfuentes.com.

[xviii] Figure 7 Chicana artist Ester Hernandez's 1982 calavera Sun Mad satirizing the Sun Maid brand and calling attention to the dangers in overuse of pesticides to people and the environment, www.esterhernandez.com.