(De-)colonizing Don Quixote in

its context: Censorship and

Visual Manipulation in Central

Spain

Written by Santiago G. Villajos

The following article presents an account on the functioning of the media and several public institutions in Central Spain. A series of political decisions and communicational resources employed by the media in the elaboration of news are analysed with the aims of explaining and understanding how these contribute to turn ontological facts into human artefacts impregnated by editorial subjectivity. This is done from the theoretical notions of habitus and social construction (Bourdieu 1992, Latour 2005). It is demonstrated through a critical approach to anthropological methods of observational participation and interpretive ethnography at home (Pujadas 2010) that subjectivity remains masked by a halo of truth through its inclusion in the context of informative programmes. It is shown from this how the processes of censorship – those omitting relevant information to society – and manipulation – those transmitting a distorted reality to the citizens – , contribute to legitimate the people who hold the power with no receiving any reprisal or penalty in return for conducting actions that may harm those they represent, whose resources they manage and benefit from.

The case study is (De)colonising Don Quixote in its Context. It was registered as a curatorial project of public mural art at the Reina Sofía Museum, Madrid in June 2013. It was by then the result of a series of processes of public engagement, participation and Street Art exploration through digital social networks that started one year before when the page 'Construir un lugar mejor sin destruir lo que tenemos' ('Construct a place better with no destroying what we have'), from now on CULM, was founded in Facebook (2012). Its main aim was to transform the historical centre of Quintanar de la Orden, the last Manchego town that Cervantes referred to both in Don Quixote (1615) and in his whole literary production (The Wanderings of Persiles and Sigismunda, 1616). The town had suffered the consequences of decades of inefficient urban and cultural heritage policies. As an alternative, the CULM project proposed the transformation of large walls, especially dividing walls visible from public space, into monumental Street Art murals that might be related to the setting's heritage.

In order to explore core-periphery dynamics from a urban perspective, this same initiative was also proposed to Madrid Destino, the public company that manages cultural productions at the capital of Spain, when four months later me as a curator was selected as a member of a group on decolonial art theory and practice that Goldsmiths University of London had arranged in collaboration with the city exhibition centre located at the old slaughterhouse, Matadero (2013). My proposal for this research group was grounded on the archaeology of landscape, both from the interpretation of Gibson's ecological theory of perception in relation to the multiscalar nature of space (Lock and Molyneaux 2006), and the spatial analyses conducted by the archaeology of colonialism (van Dommelen and Knapp 2010). It was aimed to explore Street Art as a decolonial cultural practice from a dynamic understanding of the evolution of urban landscape as a colonising agent of Nature in the particular part of Madrid surrounding Matadero, which is peripheral while being at the same time on the historical centre of the city (Villajos 2013).

Three relevant street artists – Faith47 from South Africa (FIG 1), INTI from Chile and Phlegm from the UK – were offered to the institution to paint large murals within its close environment by the river Manzanares. They were also going to paint in La Mancha in order to explore the core-periphery dynamics of interaction between urban and rural cultural settings at a larger scale from the theoretical perspective of internal colonialism (Richardson 2002, Childers 2006). However, the staff of Madrid Destino rejected the international creators. The council of the Spanish capital started instead committing murals to local artists in another district with other curators, who in some cases were also members of the Matadero research group on decolonial theory (Madrid Destino 2013). That happened short after (De)colonizing Don Quixote in its Context happened in La Mancha in August 2013 when a team of volunteers and the young Argentinian muralist Milu Correch managed to obtain support from the Council of Quintanar de la Orden, the Developing Platform for the Mancha of Toledo and people from the town. She painted a massive depiction of Dulcinea, the beloved woman of Don Quixote, as a free interpretation of the novel that was successful at the national media (RTVE 2013). It was followed by a commission from El Toboso, the town neighbour to Quintanar where Cervantes placed the origins of Dulcinea (FIG 2).

This particular success was, nevertheless quite ambiguous and rather opened a typical post-colonial situation which becomes specially evident in the responses of institutions and the media to the next steps of the project. Firstly, local authorities both in Quintanar de la Orden and El Toboso declined the option of producing the murals as pieces of public art, so a non-profit organisation had to be constituted in order to do so. Secondly, the regional government of Castile- La Mancha refused expending European funds for rural development in the creation of an intermunicipal itinerary of public mural art that may contribute to connect several towns in La Mancha and enhance tourism through paintings related to the worldwide known cultural heritage of Don Quixote (CULM 2013). This response was quite striking, since this institution had invested considerably larger funds for this particular issue in previous years that took Don Quixote as a symbol of identity of the region during the 400 anniversary of the publishing of the novel (Berenguel 2004). Thirdly, as a result of these two circumstances, when INTI found a gap after two years in April 2014 within his tight schedule to paint his free interpretation of Don Quixote in La Mancha besides his crew mate the Manchego painter Laguna626, local authorities limited the budget to less than a third of the cost of the project. The project was then supported through a crowdfunding campaign with the temporal uncertainty that characterises this method (CULM 2014). Fourthly, when Matadero Madrid was offered to host INTI and Laguna626 for a talk on their careers in a meeting of the research group, they rejected them by arguing they already have their own artists there. Furthermore, when finally INTI moved to Quintanar from Paris and finished his mural, he suffered a regrettable episode of censorship by local authorities the very same day that an article was published stating the Council's treasure had a surplus of near 3 million Euro (ABC 2014). This was followed by defamation at the regional media

The project had been conceived in the geographical context of Don Quixote on the basis of intercultural dialogue between the American cultural identities of the artists and their shared Hispanic ones, as well as with the universality of the novel. However, politicians seemed not to understand this and they censored the artwork within a delicate context in which Spanish deputies were conducting a legal reform that limited severely the freedom of expression and received worrying critiques by UN experts after its approval (Rights International Spain 2015). Politicians acted this way illegitimately, since they renounced the option of producing the mural as a piece of public art and had previously agreed on supporting it only partially as a 'free interpretation of Don Quixote' (CULM 2014a).

When INTI finished his mural and the conflict rose up, me as a curator had to negotiate with the Culture's councilor because the major was away of the town with his girlfriend in Valencia. The institution was offered to cover at least the minimum value given to the project in the crowdfunding, thus the people working on it could get a payment from the donations and the ownership of the mural artwork would become public, its status shifted from a free creation to a commission, the authorities would have the right to take decisions on the mural's iconography and to make as many changes as they wanted. Since the project also included the audiovisual documentation of the creative processes, the councilor accepted these conditions when he was being recorded with a camera. He asked in return to erase the initials 15M that INTI depicted on a scarf covering Don Quixote's mouth by referring to the 15 of May (FIG 3), the same day when Madrid both celebrates its local feast by homaging the patron of agriculture Saint Isidro and the civil movement of the indignados started demonstrating at Puerta del Sol and worldwide in 2011 for near two months. The 15M happened before local elections in Spain, due to a generalised situation of apathy to political institutions, as a result to a normalisation of corruption in the mainstream, after several episodes of police repression in Madrid and prior to the actions of Occupy at St Paul's Cathedral in London and Wall Street in New York. Although this global movement always demonstrated peacefully, some locals were highly suspicious about it and perceived the initials as an offence. It generated much tension in the public square where people started concentrating and confronting each other.

The situation became harder when INTI decided not to change his mural after the agreement with the councilor, so I had to take responsibility on the situation. I decided then to modify the artwork not by erasing the initials, but by writing '37' next to the '15', with another color and style of writing. 1537 is the date the Renaissance architect Francisco de Luna designed the bell tower behind the monstrous 1970s tower block on which both Milu Correch and INTI painted their murals. That may remain and show more evidently the regrettable misunderstanding between the artist and the institution, by emphasising one of the main aims of the project, that was driven to enhance cultural heritage at the town's centre through a dialogue between monumental architecture and modern mural art (FIG 4). INTI changed his mind when he saw me willing to go up the elevation machine. He then decided to modify his artwork and asked me to go up with him on the while he erased the graffiti. I accepted, of course, and covered my mouth behind my hands in order to state that was an act of censorship we didn't agree with while the song 'Get up, stand up' by Bob Marley was being played by DJ Pikotazos down at the town's main square, where several craftsmen and artists where also exhibiting art and handcrafts. After erasing the initials and before going down the elevation machine, INTI painted a crack on the heart he designed on the chest of Don Quixote by referring to the Mater Dolorosa that he both already painted in Puerto Rico and showed back again in Quintanar de la Orden on the posters that announced the Easter celebrations.

The problem seemed then solved, the square became silent and a double rainbow appeared on the sky, though sensibilities were hurt at different levels. For example, there were not few people who complained about the circumstance that INTI didn't painted over the four surfaces of the wall next to the one of his mural. He was offered a crane that could have been covered all the five surfaces, but he rejected that option because he depended on a driver to move himself in front of the wall after he used that kind of machinery in Istanbul (Levy 2013). It may be argued that he chose a system of elevation that didn't fit the structural complexity of the wall's setting at all, however several days prior to INTI's arrival to the town, a technician who had been providing machinery for the construction of the new buildings of the Prado Museum between 2001 and 2007 inspected the setting and assured the machine the Chilean had decided to use was adequate for accessing the whole perimeter of the wall (Matallana 2014). When INTI only painted one of the five surfaces that was actually unexpected for everyone. His professionalism was trusted from the beginning, so he didn't provide any design nor a project, but in the end the fact he only painted a side of the wall was a reason for discontent. It seems the decision of Matadero Madrid to reject him and Laguna626 had something to do with this.

The next day after INTI finished his Don Quixote, a spontaneous concentration against the mural that took place the next day at the square. The act was quite pathetic, because the it was organised illegally and demonstrators were very few. In fact, the square had been more overcrowded during the previous six days, when people from CULM arranged educational walks for students of some of the local primary and high schools while INTI and Laguna626 were creating their artworks. In any case, CULM respected this exercise of the freedom of expression by writing an official release (2014b) . Unfortunately, that occurred when a final layer of varnish was going to be applied on the wall surface in order to protect the mural against sunlight and humidity. The team then decided to wait until people calmed down, but when that happened in the late afternoon, two policemen denied the use of the platform because there was a music concert into the nearby church. Thus the mural not only was censored, but was also left unprotected and it still remains so today almost four years later.

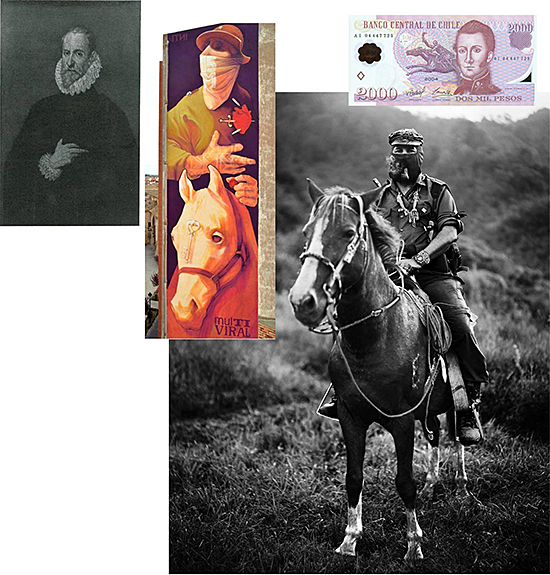

Things went worst again when the major returned from Valencia. He disregarded the agreement reached with the councilor of Culture and menaced with erasing the mural by painting it on white. By that moment INTI had already left Spain asking not to modify his artwork, and the major, a lawyer as he is, had to be informed by us in an exceptional meeting about the circumstance the Council had not any rights to modify the mural, especially because the institution decided to interrupt the payment of the minimum costs of the crowdfunding. Then a conflict of intellectual property rights arose and people who worked for the project remained unpaid despite the compromise acquired by the councilor. In addition, local authorities failed in receiving INTI's Quixote aim of producing intercultural dialogue and understanding . A symptom of this was their desire to erase also the symbol included by the artist on the right shoulder of the character and the stars on the helmet and the coin which Don Quixote holds on his left hand (FIG 5). But the most striking thing about the gathering with the major's was not his philistine and presumptuous attitude. The thing he did right before the meeting was astonishingly. He hold an interview with the regional media that was broadcasted later at the news as if the reunion had already taken place. There he stated the Council was going to demand the devolution of the money donated to CULM during the crowdfunding (CMM 2014). In order to do so they used the media to manipulate public opinion and distort the artist's intentions. So the regional TV channel referred to the symbol on the right shoulder of the character as a terrorist emblem of the Colombian FARC guerrilla, when in reality it refers to Manuel Rodríguez, one of the heroes of Chilean independence who is depicted in that country on the 2,000 Pesos notes (CULM 2014c). The media also said the position of the hands were 'obscene gestures of rappers', though that was the particular way INTI had to homage the painter Doménikos Theotokópoulos, a painter whose production was also controversial for his contemporaries, in the 400 anniversary of his death.

The things the media did not note as obvious were two. Firstly, the close resemblance between the horse of the knight and the one in the famous portrait by Jose Villa of subcomandante Marcos (FIG 5), the main philosopher of the indigenous movement of the Zapatistas whose references to Don Quixote are frequent in his writings (Krogh 2007). The media did not informed either on the relation between the star of the helmet and the Cuban Revolution (Roig 2007). The book had which had an important role in spreading this novel in Cuba because it was the first book massively printed and distributed to the population after Fidel Castro's established an authoritarian regime in 1959. Some people rejected the association between the star and the emblematic portrait of the Argentinian revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara massively reproduced since the 1968 as if it had no sense. But the association is fully charged of historical meaning because Don Quixote was also an inspirational figure to him. In fact, Che identified himself with the character in the last letter he wrote to his parents right before he was murdered in Bolivia . Even though INTI did not mentioned these references when he explained the iconography of his mural, it is obvious they are implicit in the thought of Eduardo Galeano from which he actually took the inspiration for the stars (CULM 2014c). INTI's vision of Don Quixote was a Latin American one, as it was expected. It was fully charged of crucial historical meanings for the development of Hispanic culture in the 20th century, but to some people natives from the actual geographical setting of Don Quixote, these connotations were considered as an offense rather than a gate to dialogue. Intolerant, ignorant and refusing reactions to INTI's work both in Madrid and in La Mancha shown the long term survival of a cultural logic based on cruelty similar to the one described by Cervantes in his literary production with masterly naturalism and quasi-ethnographic humanism. Although these people were to be considered a minority, nevertheless, they correlated with the ones in power and, as it is going to be shown, their logic was the one which has been imposed in the reception of the project even though many people valued positively the mural as a piece of art from its visual aesthetically positive qualities and the freedom of speech.

The interest of influential agencies like Getty Images in the mural contributed to spread the image of Quintanar de la Orden worldwide in numerous countries like Canada, France, the UK, Australia or the US, where Contemporary Mural Art is recognised as an institutional cultural practice at since the second half of the 20th century. This effect was probably multiplied in Latin America, the context where the Mexican muralists, especially Siqueiros, mostly contributed to spread these manifestations. INTI's Don Quixote even reached the headlines of a South Korean newspaper. Local politicians in power, however, denied the population the potential of benefiting from the large impact that INTI's Quixote had in the international media, quite larger than in Spain, when they rejected the public ownership of the artwork. This massive spreading of Quintanar de la Orden as a cultural place of reference that should have been positive for CULM's aim of opening the town to visitors and reactivate local economy through tourism, trade and cultural industries was however harmed by the iresolutive decisions of local politicians. They sadly transmitted an image of central Spain as a hostile place for hosting of strangers and freedom of expression. Some local citizens promoted the preservation of the mural in response by collecting signatures (León 2014). All this situation opened up a conflict that should have been solved by a judge, but none of the parts were willing to bring that to the tribunals.

The Spanish media either censored, or manipulated or silenced the project, but instead stopping, CULM went on without any institutional support. Nine more murals were painted in 2014. Almost all of them were censored and only two of them, the ones painted by street artists LOLO from Seville (FIG 6), Sabek from Madrid and Parsec! from Zamora, still remain untouched. Those disappeared were painted by Ches, a local Graffiti writer, Belmez Face from Alcorcón, one of the cities of Madrid's periphery with the longest Graffiti tradition in the country and Yago, from Madrid, who museum pieces like one of the pre-roman Iberian statuettes of Cerro de los Santos, at the National Archaeology Museum of Madrid, Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York, and William Blake's Newton, at the Tate Britain in London. In the meanwhile, the company Madrid Destino continued producing murals in Madrid. When the year finished, they did a direct comission to Laguna626 by contradicting the words of the workers of Matadero when they rejected him and INTI several months before. Laguna painted at the Chinese quarter of the city at the end of the year, the very same days when local politicians were given an opportunity to reconsider their position in relation to supporting the project. They were given the possibility of getting the whole gallery of murals for the public domain, by paying the amount of money the councilor of Culture had promised, but the major refused again this option with a surplus of near 3 million Euro in the local treasure. As a consequence, the non-profit organisation created to develop CULM succumbed into a bankruptcy and the project was stopped in 2015, when national and regional institutions expended large amounts of public money in commemorating the 400 years anniversary of the second part of Don Quixote. The town lost the opportunity to open itself to Street Artists and visitors and reactivate a more and more damaged economy.

Censorship reached a climax though in 2016, when the Toledo London-based artist Core246 painted a free interpretation of the portrait of Miguel de Cervantes published in the UK's capital in 1854 reproduced on the cover of The Wanderings of Persiles and Sigismunda (FIG 7). This mural ended the CULM project. It was produced after a political shift in the town that occurred the year before, when the new major incorporated the CULM project to the agenda of his party during the elections. As a result, me as a curator was working for a period of five months to the Council, but the first two months the institution did not legalised my situation, so I was working without a formal agreement and was not paid during that period. The main tasks developed during those two months were focused to curating a memorial exhibition on Cervantes for the local exhibition centre 'Casa de Piedra' that was firstly proposed by me to the previous major three years before in 2012. The exhibition was conceived as a monograph on the Persiles, because of the links between this last known Cervantine novel and Quintanar de la Orden. In order to do so, all the editions of the book stored at the Spanish National Library in Madrid (BNE) were carefully inspected in order to produce a record of all the visual culture on the Persiles existing at the BNE.

Then an image of Cervantes appeared on a book with a post-script stating it was an authentic portrait of the writer originally painted during his lifetime. The words were signed by Louisa Dorothea Stanley, the translator of the 1854 London edition of the novel. I considered the finding to be extremely relevant, so by the moment the Council of Quintanar de la Orden finally made my contract regular in December 2015 the National Library's Director of Broadcasting Department got to know about it in a meeting. Nevertheless, the institution strikingly never supported the finding. On his part, the major of Quintanar started coercing me two months later. He asked me to interrupt my agreement with the Council because if not the previous major and another Councilor were going to arrange a motion of censure. These pressures came due to two main reasons. First, the National Library sent a list with the insurance costs after approving the loan of twenty books that were valued more than a hundred times over the costs that private companies provided for the same service. Second, my dismissal came came when the illustrator Gijs Vanheee, curator of the public mural art gallery of Mechelen, Belgium, was about to paint a large mural in Quintanar within the CULM project, this time finally as public art. Consequently, the project of donating the project's to the town was aborted when it was closer to occur than ever. Finally, this series of contradictory decisions lead to some emails in which the broadcasting director of the National Library, who first signed the permission for lending the books after reading a report on the conditions of the exhibition space, then moved to say the conditions were not adequate.

It can be summed up that the exhibition was cancelled due to a series of political negligences, among which it can be found: (a) inattention to the criteria of expert staff signed to organise the exhibition in terms of budget; (b) lack of staff signed with the aim of providing 24 hour surveillance in the exhibition space; (c) interruption of the agreement signed with the expert on cultural heritage because the exhibition was seen as an unnecessary action for the town's development, that also aborted the creation of a GIS (Geographical Information System), a professional training program for the agents in charge of the local cultural production, the enhancement of abandoned public properties, the restoration of a historic monumental bell tower, the enlargement of an urban gallery of Street Mural Art and the creation of an interpretation centre to introduce the natural and cultural heritage of the environment.

As a result of these mistakes, the actions driven to transmit the scientific knowledge produced within the curatorship into society were reduced to the execution of a large mural painting. That happened at the urban landscape of the town's historical centre because the curatorial project also included the production of large murals there related to the visual culture of the Persiles. As my attention to the portrait of Cervantes was considerably increasing, thus a mural interpreting this image was carried out independently by CULM and Core246, the artistic name of Ignacio del Cerro Arrabal, graduate in Fine Arts at Cuenca by the University of Castile- La Mancha. The more research that was done on it, the weaker the arguments against its authenticity became. For instance, it is particularly elucidating that the only two times this portrait was assessed (Pérez 1916, Givanel and Gaziel 1946), the authors argued the character that Stanley mentioned in his post-script as the owner of the portrait did not exist. However, my recent research demonstrates his existence. He was a British ambassador in Madrid between 1840 and 1843 and collected Spanish art, but no further studies have been done about his collection, that was dispersed after it was completely auctioned in 1862, when Arthur Ingram Aston, the man under consideration, was dead for two years.

The same media which focused their attention on the murals of Milu Correch, INTI and Laguna626 were contacted back again through a press release, but the censorship remained as it was imposed to the project after the Chilean painted his Don Quixote. There were just three different media who attended the notice. Firstly, a local digital newspaper reproduced totally the press release (Villajos 2016). Secondly, another one that modified the press release and included fake information (Mancha Información 2016). One year later that moved the new local government's councilor of Culture to present a complain against me in court. Thus the political shift did not matter. Conversely, the rejection response was even stronger this time. It produced a grotesque situation in which the media was driven by the political authorities towards delinquency because they acted unprofessionally, without contrasting the information just because they were conditioned by the payments of the Council to have income. Nowadays, the situation is even more complicated, because the motion of censure was finally done last December, so the councilor of Culture is not that anymore. Thirdly, the public regional TV produced again a distorted report for the news that converted ontological facts into editorial subjectivity. Since this time there was nothing happening at the street, a journalist of the TV channel called me by phone. He already read the press release published by the local media (Villajos 2016) and arranged an appointment in order to interview me in Quintanar de la Orden. Although I had to move there expressly from Madrid, the channel did not cover any expenditures. The journalist also asked me to send some pictures via email to him, so he could illustrate the report. The images sent to him were three. (a) a series of demonstrative sequences where different portraits of Cervantes are compared in terms of morphology by overlaying them in a scale ranked in 10 different grades of mixing; (b) the 1854 engraving with the portrait; and (c) a detail of Francisco Pacheco's San Pedro Nolasco redeeming the captives, where Asensio identified a portrait of Cervantes which the overlaying analyses shown to be very similar to the 1854 engraving in structural terms, despite the hairstyles differ considerably (FIG 8). The audiovisual report was broadcasted the next day at 14.00 in the cultural section of the news.

In order to analyse the editorial discourse of the channel, the whole interview was recorded in parallel through a sequence shot. That allowed a triangular comparison between this recording, the original press release and the audiovisual assembly that was finally broadcasted. There are nine points that deserve attention from this triangulation. First, there was a lack of attention and/or respect in the reproduction of my surname that was written as Villejas, not Villajos as it appears in the signature of the press release, as I introduced myself when the interview started and also as it appears in the email address from which the pictures were sent to the journalist. Second, there was a lack of respect or consideration towards the work of Core246, whose mural reinterpreting Cervantes was not mentioned even though he is natural from Castille- La Mancha and he graduated in Castille- La Mancha University, the region the TV channel works for. Third, there was also a lack of attention and/or respect in the reproduction of my profession. Despite I introduced myself as 'art historian, anthropologist, archaeologist', the journalist just write 'historian'.

Fourth, there was an omission and/or lack of respect towards the works carried out by CULM at the public space of Quintanar de la Orden since August 2013 that were not paid by the major in 2014 when he broke the compromise acquired by the councilor of culture of covering the minimum cost of the crowdfunding the very same they an article published the Council's treasure has a surplus of 3 million euros. Fifth, there is an omission and/or lack of respect in including any links between the portrait of Cervantes and the cultural heritage of Quintanar de la Orden, which in this particular case is given by the Persiles. Sixth, there is lack of attention and/or respect at the time of illustrating the scientific theories of my research. Both the portrait of Francisco Pacheco at the Provincial Museum of Seville and the demonstrative overlaying sequences were left out of the final assemblage, despite they were explained to the journalist right before the interview. Seventh, there was a complete lack of political content. Every reference to the interruption of the working relation between me as a researcher, the Council of Quintanar de la Orden and the manieuvre of the ruling political party to keep the power were excluded by the journalist. Eight, any information concerning to my professional background as a reseracher was also omitted: there were no references to my professional dependence to the Council of Quintanar de la Orden, nor to my previous status as a university professor in Ecuador, nor to my master studies at the UCL and Granada University.

In conclusion, this last news report and the empirical evidence presented before it within this article show that scientific research is socially constructed as a leisure activity or hobby rather than a profession requiring high qualifications, important amounts of time, resources and discipline in order to reach satisfactory results. This position contributes to detect and feed a dominant opinion of Central Spanish society back in relation to research and development policies. That means research is generally considered unsubstantial or unnecessary for human development and researches in Spain have to be well related with the circles of power to get a professional recognition. Their option is otherwise going abroad in exile. This context is worrying and may be clashing with several human rights like the right to work. The journalist reproduced this topic twice before he leaved: “Don't you think about going back to Ecuador?”; “Actually, it is actually complicated for you [the scientists]”. Finally, it can be pointed out that a relation between the highly debatable issues this article includes demonstrates the prevalence of a longue durée in the logic of the coloniality of power which is most likely traceable back to the shaping of Early Modernity in Spain. In this sense, critical views to the particular work of the historian Americo Castro (1966) may provide fruitful evidence for understanding these issues and generating alternative solutions.

Santiago G. Villajos is a PhD student at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM).

List of references

ABC, 2004. Quintanar de la Orden cierra su presupuesto con superávit. ABC, 05/04/2014 (online, http://www.abc.es/toledo/20140405/abcp-quintanar-orden-cierra-presupuesto-20140405.html, 14/02/2018)

Berengel Vázquez, Juan, 2004. La ruta de Don Quijote: cultura e ingenio para un desarrollo sostenible. In: Azcárate Bang, Tomás, Jiménez Herrero, Luis y Marín Cabrera, Cipriano, 2005. Diálogo sobre Turismo, Diversidad Cultural y Desarrollo Sostenible. Barcelona: Instituto de Turismo Responsable, 117-118

Bourdieau, P., 1992. The logic of practice. Cambridge: Polity Press

Castro, A., 1966. Cervantes y los casticismos españoles. Madrid: Alfaguara

Childers, W., 2006. Transnational Cervantes. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

CMM, 2014. Informativo 14 horas. Castila- La Mancha Media, 09/04/2014. Min 00:35 (online,

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0BxQwLLbE5SmfVGVLZkdnNGIwWGM, 14/02/2018)

CULM, 2012. Foundational post. Construir un lugar mejor sin destruir lo que tenemos, 6 June 2012 (online, https://www.facebook.com/CULM.streetart/posts/234446866667231, 14/02/2018)

CULM, 2013. Proyecto de intervención artística Grupo de Acción Local Dulcinea - Leader. (online, https://drive.google.com/open?id=1-tLASdOR6FvNvTxwtsnVc5vUxe4Mcwe3, 14/02/2018)

CULM, 2014a. Pintar el Quijote más grande del mundo, campaign for the project (De)colonizando el Quijote en su contexto. Goteo.org, (online, https://www.goteo.org/project/pintar-el-quijote-mas-grande-del-mundo, 14/02/2018)

CULM, 2014b. Comunicado Oficial CULM. Construir un lugar mejor sin destruir lo que tenemos. 6 April 2014 (online, https://www.facebook.com/CULM.streetart/posts/497441793701069, 14/02/2018)

CULM, 2014c. En vista a las equivocaciones difundidas por la notica emitida en el día de hoy en TVCLM... Construir un lugar mejor sin destruir lo que tenemos. 6 April 2014 (online,

https://www.facebook.com/CULM.streetart/posts/498051880306727, 14/02/2018)

Givanel Mas, J., and Gaziel, 1946. Historia gráfica de Cervantes y del Quijote. Madrid: Plus Ultra

Krogh, J. A., 2007. The Spirit of Don Quixote in the Zapatista Revolution. BA Thesis. University of Oregon (online, https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/9513, 14/02/2018)

Latour, G., 2005. Reassembling the Social: Actor Network Theory, an introduction. Oxdord: Oxford University Press

León Díaz, J., 2014. Se abstenga de destruir el mural “El Quijote” del artista INTI. Change.org (online, https://www.change.org/p/ayuntamiento-de-quintanar-de-la-orden-se-abstenga-de-destruir-el-mural-el-quijote-del-artista-inti, 14/02/2018)

Levy, R., 2013. INTI New Mural in Istanbul, Turkey. Street Art News, 18/06/2013 (online, https://streetartnews.net/2013/06/inti-new-mural-in-istanbul-turkey.html, 14/02/2018)

Lock, G. & Molyneaux, B. (eds), 2006. Confronting Scale in Archaeology: Issues of theory and Practice. New York: Springer

Madrid Destino, 2013. Paisaje Tetuán. Intermediae, 01/10/2013 (online, https://www.intermediae.es/proyectos/paisaje-tetuan, 14/02/2018)

Mancha Información, 2016. El historiador quintanareño Santiago González Villajes rescata el auténtico retrato de Miguel de Cervantes. Quixote Información, 06/04/2016 (online, http://manchainformacion.com/noticias/43137-El-historiador-quintanareo-Santiago-Gonzlez-Villajes-rescata-el-autntico-retrato-de-Miguel-de-Cervantes-, 14/02/2018)

Matadero, 2013. Decolonizando el conocimiento y las estéticas: grupo de investigación. Matadero Madrid (online, http://www.mataderomadrid.org/ficha/2470/decolonizando-el-conocimiento-y-las-esteticas.html, 14/02/2018)

Matallana, 2014. Personal communication, April 2014

Pérez de Guzmán, J., 1916. Los retratos de Cervantes. Arte Español, 3, 52-147

Pujadas, J. J. (coord.), 2010. Etnografía. Barcelona: Universitat Operta de Catalunya

Richardson, N.E., 2002. Postmodern Paletos: Immigration, Democracy and Globalization in Spanish Narrative and Film, 1950-2000. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press

Rights International Spain, 2015. UN Urges Spain to Drop Legal Reforms Threatening Human Rights. Liberties 04/03/2015 (online, https://www.liberties.eu/en/news/un-law-citizen-security-penal-code/3183, 14/02/2018)

Roig, A. A., 2007. Cabalgando con Rocinante. Una lectura del Quijote desde nuestra América. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, 12, 38 (online, http://www.scielo.org.ve/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1315-52162007000300014, 14/02/2018)

RTVE, 2013. Telediario 21 horas. 24/8/2013. Minute 34 (online, http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/la-2-noticias/2-noticias-20-08-13/2000408/, 14/02/2018)

van Dommelen, P. & Knapp, B., 2010. Material Connections in the Ancient Mediterranean: Mobility, Materiality and Identity. London: Routledge.

Villajos, S. G., 2013. (De)colonizando la urbs como práctica artística. El arte urbano como práctica (de)colonial. Estancias de investigación. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (online, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KjXC-7cyfA5knHs-FqQY4tIO8c04zo58/view?usp=sharing, 14/02/2018)

Villajos, S. G., 2016. Rescatado el retrato de Miguel de Cervantes. Mas Castilla- La Mancha, 05/04/2016 (online, http://www.mascastillalamancha.com/2016/04/05/quintanar-de-la-orden-rescatado-el-retrato-de-miguel-de-cervantes/, 14/02/18)