August 10, 2016

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Interview by Mylène Ferrand Lointier

Hans Ulrich Obrist, could you please tell us about the origins of your collaboration with Bruno Latour?

Towards the end of the 1990s, simultaneously so to speak, Peter Weibel and I became interested in Bruno Latour’s work. Weibel went to see him, and I did the same thing. Barbara Vanderlinden and I invited Latour to participate in the reflective core group of the exhibition Laboratorium in Anvers.[1]

One can say that this was his first participation in an exhibition. It was a medium he had never worked with before – books and lectures being his own media. He became co-curator of a Laboratorium section with us, and together we invited him to guest curate a part entitled “Table top experiments”. Often, one cannot identically relive scientific experiences, due to changing geographic, climatic, temporal conditions etc. What we were dealing with here was a series of repeated experiments by Peter Galison, Caroline Jones and many others. Latour personally reconstructed a Pasteur experiment. He also invited artists like Panamarenko and architects like Rem Koolhaas to talk about this idea regarding the experiment as a public demonstration; to make a public experiment. This is what my first collaboration with Bruno Latour was about. Today, the circle closes at the ZKM since the museum possesses the archive of this demonstration in Anvers. Shortly after it took place, Peter Weibel invited Bruno Latour to conceive the exhibition Iconoclash[2] at ZKM, which became the first large-scale exhibition by Bruno Latour. In a way similar to how I invited him to Laboratorium, he invited me to contribute a section to Iconoclash. The roles became reversed. At the time, I had invited the Japanese architect Arata Isozaki to remake Electric Labyrinth that was originally made at the mythic Triennale 1968 by Giancarlo De Carlo in Milan. Due to a clash with students, this work was completely ruined on the day of inauguration and hence could never be seen. We therefore remade this extraordinary piece with Isozaki, an architecture pioneer, including a feedback loop, a cybernetic installation from the beginning of cybernetics where the walls are moving, where there are images of all sorts of history and where the spectator is immerged in this technological environment. It is neither an “iconophilic” nor an “iconoclastic” work, yet all the same a work of “iconoclash”.

What does your participation in the exhibition Reset Modernity! At ZKM consist in?

I always kept up the dialogue with Bruno Latour. He talked to me about his Facing Gaïa conferences that resulted in this extraordinary book[3] and the idea of this triangle: Globe – Territoire – Gaia, whereas I, for my part, had been planning for a long time to interview James Lovelock who lives in Chesil Beach in England. Bruno Latour sent me his questions for James Lovelock, which were added to my own. I spent a day with Lovelock at his place and the interview, which was filmed, is part of the exhibition. A transcript is also available in the catalogue. This is our main collaboration.

Otherwise, Bruno Latour and Martin Guinard-Terrin[4] also took part in a conversation about Les Immatériaux[5], the exhibition made by philosopher Jean-François Lyotard at the Centre Pompidou in 1985. At the moment we are working with Daniel Birnbaum and Philippe Parreno on an exhibition by Lyotard named “Resistance”. This idea that a philosopher makes an exhibition and makes us of the exhibition format, the idea of the “Gedankenausstellung” or “thought exhibition”, also brings us over to “Immatériaux”, an exhibition that Latour had participated in, by the way, at the same time as he expressed a very critical attitude towards it.

Parreno, who had followed the lectures by Pontus Hultén, Daniel Buren, Sarkis and Serge Fauchereau at the EHESS during the 1980s, remembered that Lyotard had talked to him about a second project that he wanted to realize on the topic of resistance. In a sense, it is the complete opposite of Immatériaux and its super-fluidity, yet adding Lyotard’s reflections on what resistances could be. Of course it is necessary to understand the word resistance in both the political and the physical sense.

After this, we discovered that what Lyotard wanted was not really to make just another “Centre Pompidou-exhibition” including architecture and hundreds of artworks, rather he wanted to put together an exhibition-movie, a group exhibition within a film format. We hence found ourselves making a film with different protagonists like Gayatri Spivak, Bruno Latour and a number of other artists and architects. Albert Serra and Rirkrit Tiravanija will direct the film. This will be the first “Gedankenausstellung” that we will curate in the name of the absent Lyotard, and hence the first “Gedankenausstellung” curated by a dead person!

At this occasion, we made a filmed interview[6] with Bruno Latour about his way of relating to the “Gedankenausstellung”, about his criticism of Lyotard, his bad memories from Immatériaux. Here, we are also talking about this trilogy that was developed for ZKM.

Of course I kept thinking that I had to go to see the exhibition at Karlsruhe, and since I would never miss an exhibition by Latour, Bruno and Martin suggested I should come to the vernissage, not least since there were these days of conversation – into which I eventually became implicated.

The idea of producing new rules to fabricate knowledge, is an important one. There is a standard format of the colloquium, of the conference and the debate, that always follows the same pattern. It is extremely conventional. What is interesting is the fact that the medium of the exhibition, for more than a century – because if we consider Marcel Duchamp it is already present – the exhibition has incessantly invented new rules of the game. Undoubtedly, the world of the exhibition has lessons to teach us. When one makes an exhibition, one invents a new set of tools. Exactly that is the case here, with this extraordinary work Museum of Oil by Territorial Agency (John Palmesino, Ann-Sofi Rönnskog) and Greenpeace, one of my preferred works in which it is proclaimed that resources need to stay in the soil. It is against extracting hydrocarbonate due to its devastating effects. Territorial Agency has really invented a new set of tools with these large, obtuse signposts, that resemble picture frames and that represent these strata, these archaeological foundations, and this devastation produced by the oil industry, and that is, at the same time, on-screen, with all its data, the big data in relation to this, and assembled by the activists. The obtuse also, of course, makes you think about Claude Parent, and that is a real experience. It is not a book, rather it is a new, invented set of tools. When thinking about the discovery of new rules, it is also interesting to try to anchor this in a more discursive reflection, bringing us back to the multiple and archipelagic discussion groups that took place during the exhibition’s opening days.

What is your opinion about the situation and the political remobilization of art that we are witnessing today?

There is a sort of expansion where the walls of the silos are becoming porous, but where this is not necessarily a question of art or architecture. Alexander Dorner, the famous director of the State Museum of Hanover at the beginning of the 20th century, said that it was necessary to find “ways beyond art”. We have to consider the practices of the extraordinary, extremely politicized – in both an artistic and activist sense – poet Etel Adnan, who had realized a very political journalism in Lebanon and who, at the same time, creates a sense of hope through her paintings, her poems and her large-scale theater plays about the Lebanese civil war, etc. etc. To me, she is the big inspiration for the 21st century.

It is therefore not necessarily a matter of going beyond the questions of art, but about going beyond art. Let us pick up once more the example of Museum of Oil, and I will not be able to tell you if it is a project of architecture, urbanism, art, activism… “Neither is that the place where the question is located”, as Maurizio Nannucci would say. The question: an urgent project for the 21st century, as an intrinsic feature of the modern exhibition of art and architecture residing in its form, in its invention of a set of tools.

From now on, what is important is not so much the category as the practice, and more generalist practices. I also think that it is necessary to create a pool of all knowledges to be able to pose the big and urgent questions of the 21st century, regarding issues like ecology and inequality. As scientists, artists or architects alone, it is impossible to resolve these problems. This is the reason why more and more collectives are created. This has been the case for a long time in the sciences, where the Nobel Price is often given to a group of persons. We no longer live in an era of isolated geniuses, but rather in an era of research networks. It is interesting to see this happen in art and architecture.

What is the place of the non-human, notably of animals?

Exhibitions are about making junctures. If I was hanging this object next to the other, and if these objects were artworks, I would be making a juncture between two works of an exhibition. This is the classic curator-exhibition. Since the 1960s, we have been moving beyond objects, hence there are also “quasi-objects” as Michel Serres calls them, there are also “non-objects” as demonstrated by the dematerialization of art, and also the “hyper-objects” that Timothy Morton talks about, such as climate change etc. The curator today makes junctures between people, visitors, humans, but evidently also animals.

Richard Hamilton told us that when he and Dieter Roth were making exhibitions, they were thinking that it was not only for the human eye. At Serpentine Gallery in London, these two artists hung the artworks lower than usual so that the hundreds of thousands of dogs that were strolling in Hyde Park should be able to see them. I think that we are only seeing the beginning of this phenomenon. We find the same thing in Pierre Huyghe with his multiple perspectives, in Philippe Parreno’s latest exhibition[7] where bacteria uptown decide the unfolding of the piece downtown. The decision is taken by bacteria, not us.

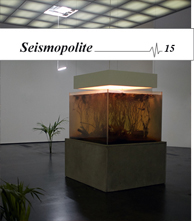

The fish and axolotls swimming in Pierre Huyghe’s aquarium, have they decided their own destiny? Is this not a representation of the privileges of one species over another, of interspecific inequalities ?

In fact this reminds me of Snowdon Aviary by Cedric Price at the London Zoo, constructed in 1965 and that changes with time according to the weather and the wind. Cedric Price embraced the utopia that birds would be able to decide for themselves; if they wanted to leave the aviary, they could do so; they would even be able to fly away with the aviary and bring it outside the zoo.

Also, the 20th century has been very preoccupied with this idea of human proclamations; it was the era of the manifest. Etel Adnan always told me that from the beginning of the 21st century, everything is a matter of listening, but that it is not only necessary to listen to humans – also objects, animals, etc. I think that Etel Adnan’s answers to these questions are very important. I think that she is one of the foremost writers of the 20th century, and particularly of the 21st. She marks this paradigm shift. With Daniel Birnbaum, Negar Azimi and other friends, we launched a campaign to promote Etel Adnan for the Nobel Price. There you have yet another urgency!

NOTES

[1] At the Provinciaal Fotografie Museum in Antwerp, Belgium, 27.06. 1999 – 03.10.1999.

[2] Iconoclash – Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion and Art. 04.05.2002 – 01.09.2002, ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany.

[3] Bruno Latour. Facing Gaia. Eight lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Polity Press, to be published in English in 2017.

[4] Reset Modernity! is signed by four curators: Bruno Latour, Martin Guinard-Terrin, Christophe Leclerc and Donato Ricci.

[5] Exhibition Les Immatériaux at the Centre Pompidou, Paris. Curators: Jean-François Lyotard, Thierry Chaput. 28.03.1985 – 15.07.1985.

[6] To see the interview: http://modesofexistence.org/what-is-a-gedankenausstellung/

[7] Philippe Parreno, If this then else, Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York. 05.03.2016 – 16.04.2016