Nepal: The rise and ‘ban’ of the collateral

How a young Nepali painters’ works raised questions on artistic freedom in Kathmandu, the City of Temples.

By KANCHAN G. BURATHOKI

On Tuesday afternoon, 11 September 2012, when the exhibition ‘The Rise of the Collateral’ had only nine days left to conclude, after having been at display at Siddhartha Art Gallery in Kathmandu since 22 August, a group of men from the World Hindu Federation Nepal Chapter stormed into the gallery and threatened the artist with life for insulting Hindu gods and goddesses in his paintings.

They asked the artist, 27-year-old Manish Harijan if he knew what had happened to Late M. F. Husain in India for making profane paintings of Hindu deities. Husain had lived a life of self exile in the United Kingdom until his death last year. Harijan too, could face similar consequences, they declared.

Instead of providing security for the artist and the gallery, a group of policemen arrived at the gallery the same evening to seize Harijan’s paintings and to arrest him. They too, were of the opinion that his paintings were blasphemous. Regardless of their personal judgments, neither did they have the right to take Harijan’s works nor did they have proper papers to arrest him.

An official from the District Administration Office (DAO) of Kathmandu later arrived at the gallery and prepared documents to seal the space. No clarifications were made to the artist or to the gallery’s Director Sangeeta Thapa, before they locked up Siddhartha Art Gallery with 11 paintings by Harijan inside it. The two were simply asked to report to the DAO the following morning at 10 am.

As the news of the incident spread in local and international media, it rippled a series of opinions and articles condemning the World Hindu Federation Nepal Chapter as well as raising concerns on freedom of expression in Nepal. Local artists came together to show their solidarity and support, while mixed reactions from people, for and against the artist, flooded online comment boxes and newspapers.

By the end of the week, several rumors were floating in the news, some of which had no reason or rhyme. Things had relatively simmered down. A month has passed by and the events that followed the incident in Nepal’s contemporary art scene, since then, have taken several twists and turns – the ending of which is as unexpected as the attack on the artist and his artworks, themselves.

“At first, I thought it was a bit funny and I was trying to explain my works to the men from World Hindu Federation,” narrated Harijan, three weeks after the incident. “But when they said that they would burn my paintings and mentioned M F Husain, I realized that they were serious. That’s when I got scared and decided to back off.”

The group of men was led by executive board member of WHF and former Colonel of Nepal Army, Hem Bahadur Karki. It was around mid-afternoon when they arrived. At that time, Harijan was discussing his works with fellow Nepali artist, Jupiter Pradhan. “Had I been alone in the gallery, they would have beaten me up,” said Harijan, describing the then tense atmosphere and still feeling uneasy about it. It was later known, through the Gallery’s staff, that the men had been visiting the Gallery and taking pictures of the paintings since the past few days.

Although security was eventually arranged for him, Harijan stayed at different places for two weeks before moving back to his rented space, where he lives by himself. He also switched off his cell phone for a week and avoided all media attention.

The youngest of eight siblings, Harijan comes from a village in the western part of Nepal. He moved to Kathmandu in 2005 and enrolled at the Lalit Kala Campus (Fine Arts Campus) in the intermediate level. After two years, he joined Kathmandu University Center for Arts & Design (KUarts) from where he graduated with a Bachelors of Fine Arts degree in 2011. Currently, he works as an art teacher at Kendriya Vidyalaya, a school run by the Embassy of India in Kathmandu. Harijan’s sisters are in the village and his brothers, who are working in the Gulf, are all unaware of the incident.

A religious attack?

The Rise of the Collateral is a series of works made as part of the residency he was awarded by Kathmandu Contemporary Arts Centre (KCAC) in September 2011. The centre has been providing residency grants to local and visiting artists since 2009 and Director Thapa is a co-founder of KCAC.

Harijan received Nepalese Rupees 30,000 (approximately 365 US dollars) for the eight-month long program, unlike accusations made by WHF that Harijan was a ‘Dalit Christian’ who had been paid by Department for International Department (DFID) of the UK government to make sacrilegious paintings.

‘Harijan’ as a caste belongs to the Dalit group in Nepal, who were traditionally considered untouchables. Assumptions were, therefore, also made that his paintings expressed his suppressed anger towards the Hindu caste system.

While one local writer turned the incident into a caste-based issue, Harijan rebuked, “I grew up in a very broadminded community, where I never experienced any discrimination. I identify foremost as an artist and that’s how I would like to remain.”

More importantly, Harijan also identifies as a Hindu and this plays a crucial role in the content of his works.

“I draw inspirations from my own culture and religion,” Harijan stated. “These paintings collectively comment and question the influences of the West on our culture. It is a combination and therefore, collateral of the East and the West.”

When the DAO locked the gallery on 11 September, it was still unknown what WHF had exactly found offensive in Harijan’s works. Later it was revealed that a complaint against Harijan, Siddhartha Art Gallery and KCAC had been officially filed at the DAO on 7 September by a woman named Sindhu Pathak, a WHF member. Pathak had filed a request to the DAO to close the exhibition; to seize the offensive paintings; to investigate the artist, the gallery and KCAC; and to punish them as per the law.

The two page complaint outlines a total of six paintings as offensive – ‘Super Natraj’, ‘Super Kali’, ‘God creates us, god loves us’, ‘Upside down mountain’, ‘Real Buddha’, ‘108 Gods’ and ‘Captain America playing with Bhairab.’

Among the most talked about work is Super Kali. The painting depicts a female figure in black with multiple hands and snakes for hair. She wears a superwoman costume and shows a middle finger. Pathak’s complain stated that Super Kali was a vulgar work which insulted all women and Goddess Kali, especially because of the middle finger which is a ‘form of the male sexual organ’.

“It was never my intention to insult or disrespect anyone through my paintings. People have misinterpreted my paintings and once they understand the actual meaning, they will not find it offensive, shocking or extreme,” reiterated Harijan.

“We live in a patriarchal society where women face various discriminations,” explained Harijan in a statement of his artworks submitted to the DAO. “The painting is about the rise of feminine energy against such discriminations. It brings together our traditional symbol of feminine power, Goddess Kali, with the Western world’s symbol of super natural power.”

Super Kali represents an urban Nepali woman in the mixed forms of Goddess Kali (East) and Superwoman (West). It is not Goddess Kali being represented as a Super Woman or vice versa, as has been the understanding.

Hundreds of Hindu temples and shrines, big and small, in Kathmandu have explicit sculptures and paintings of gods and goddesses in sexual union. They’ve been a part of our religion and culture since centuries. “If art is going to be banned then what about our traditional religious works? How do you define vulgar? Where and how can you draw a line?” questioned artist Ashmina Ranjit, at one of the gatherings campaigning for the freedom of expression.

In response to the call for ban of Harijan’s painting, a Facebook group titled ‘Let’s Censor ART’ was created by Nepali artists. People posted images of traditional sculptures and paintings that were ‘censored’ by digitally adding clothes to them.

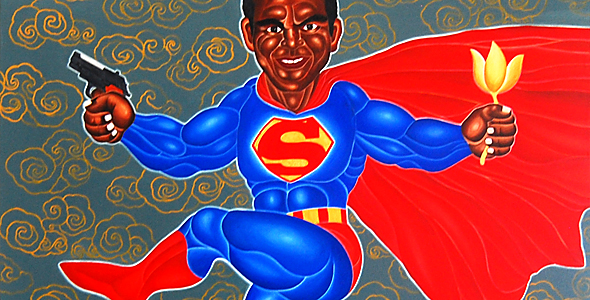

Similarly, Super Natraj shows an ordinary man, emulating the posture of Natraj – Lord Shiva in the form of a cosmic dancer – in Superman’s costume. Once again, the painting is of a man with traditional Hindu beliefs but who is also drawn towards a foreign culture. The man holds a lotus in one hand, and a gun in the other. “Each person has two sides, a violent one and a peaceful one,” Harijan put in.

Talking about super heroes, the artist revealed, “I come from a poor family and I couldn’t afford to buy comics as a child but knew about super heroes in Indian comic books.” It was only in Kathmandu that he learnt more about super heroes. In 108 Gods Harijan has painted 108 super heroes, the references for which was taken from DC and Marvel comic websites. “I have also done a simulation of Jirapat Tatsanasomboon’s painting in Captain America playing with Bhairab,” he added. Tatsanasomboon, a Thai artist, is also known for his superhero paintings.

Another major painting in question was Upside down mountain. A muscular man is flying across the sky, with an upside down mountain in one hand and a bottle in the other. The narrative is derived from the Hindu epic of Ramayana in which Hanuman, a revered deity, carries an entire mountain when he can’t find the particular herb he is asked to bring.

“The mountain in my painting is upside down, barren and dry because of global warming,” said Harijan and continued, “The herb ‘Sanjivani’ is inside the bottle but many overlooked this and thought that the man was carrying a bottle of alcohol. The herb is a metaphor for amrit (nectar of immortality) that could save the world.”

‘Jeopardize harmonious relations’

Article 12 (3, a) of Nepal’s Interim Constitution guarantees every citizen the ‘freedom of opinion and expression’. However, it also states that:

‘…nothing in sub-clause (a) shall be deemed to prevent the making of laws to impose reasonable restrictions on any act which may undermine the sovereignty and integrity of Nepal, or which may jeopardize the harmonious relations subsisting among the peoples of various castes, tribes, religion or communities…’

“As much as I am allowed to express my thoughts, people are also allowed to disagree and debate. But there shouldn’t be censorship,” said Harijan. “There would be no meaning if a person can’t express himself or herself. God, the form of gods, the philosophy of religion and even super heroes – were all created by man. Why censor something that man himself created?”

“Experimentation is important for new discourses in art and in my works, I am trying to connect my culture and religion to the contemporary context,” Harijan stated and further opinioned, “The misinterpretation of my works goes to show how much of a narrow-minded society we live in.”

Regardless of wherever in the world he maybe, Harijan said that he would continue to paint similar subjects and motifs because his culture and religion will always influence and inspire his art. “Who knows, in the future, they may have an even stronger presence in my work?” he mused.

Harijan is not the first person to make references to gods and goddesses or to question Hinduism in contemporary Nepali art. Artist Asha Dangol has painted several time deities holding guns, grenades and sickles in their multiple hands. In 2009, Ragini Upadhyay Grela painted a goddess with computer wires for hair and a light bulb for her third eye as she sat atop a computer monitor instead of a lotus flower. Ashmina Ranjit has openly derided, through her performances, the discriminations Hindu women face during menstruation.

Neither is Superman a new idea. Only last year itself, Laxman Karmacharya exhibited a painting that showed deity Bhairav flying across the cityscape in a superman costume. The work was titled ‘S. Bhairavman’.

There has never been such a severe attack on art and artist in Nepal due to religious issues. “Previously, artist Chandra Man Maskey had been imprisoned for ridiculing the then Rana rulers. But since then, no artist or art institution in Nepal has ever been incarcerated or investigated by the state,” informed Gallery Director Thapa.

Nonetheless, one can’t say that we haven’t had any opposition due to religious concerns. In 2010, French artist Karl Knapp’s monumental Buddha was banned from being exhibited at the Patan Durbar Square by locals of the area. Knapp’s Buddha was constructed out of recycled plastic bags collected from garbage dumps. It was a commentary on the growing pollution of the city. Locals, however, took it as an insult to Lord Buddha and their faith. Even so, the work was still exhibited at a different location and no damage was done.

A political attack?

More than the issue of religion and hurting people’s sentiments, Thapa feels that her family’s political connection maybe the foremost reason of WHF’s attack on Harijan and her Gallery.

Thapa is the daughter-in-law of former Prime Minister Surya Bahadur Thapa and her father too has been a Congress member for many years. The former PM had recently announced that their party would not accept reinstating Nepal, which became a secular Federal Democratic Republic in 2008, as a Hindu Kingdom.

“I feel that the WHF found something to further their political agenda in order to emerge as a defender of old values and faith in the changed political scenario of Nepal,” she expressed and continued, “The work happened to be in my gallery and it gave them an opportunity to politically embarrass my father and father-in-law. Lastly, Manish also happened to be a Harijan which dragged in the issue of caste.”

Peaceful protest

On the evening of September 12, artists and supporters gathered at the gallery to discuss what the incident could mean to Nepali art. Despite the tension, many agreed that it was an achievement for contemporary Nepali arts and that it should take be as an opportunity to fight for the freedom of expression.

The following morning, September 13, a peaceful protest was staged in front of the DAO, while Harijan and Thapa were in a meeting with the Chief District Officer, Chudamani Sharma.

“Unlike what we had expected, no one from WHF was present at the meeting, but in a way I think that worked to our advantage and we diffused a situation that could have been worse,” said Thapa. It was late afternoon when the two came out of the DAO’s office, announcing that the Gallery would be reopened and none of Manish’s works would be seized. It was a moment of victory for all artists.

Unfortunately, it only lasted momentarily.

Gallery closure and artist silenced

Among the five agreements made between DAO and Harijan and Thapa, are points that outline that ‘the debated paintings will not be shown in public again’ and ‘any works offending any religion will not be made or sold’ by the artist and the Gallery.

Artists, who were supporting and campaigning for the artist, the Gallery and for the freedom of expression, feel that signing the agreement was a big blow to the artist community and to contemporary Nepali arts. In a way, they feel betrayed by both Harijan and Thapa.

“Given the time and situation, I feel that I did the right thing because not signing it could have worsened the debate – it would have become political, religious as well as ethnical,” defended Thapa. “And we have all seen the kind of violence such issues have spurred in our neighboring countries India and Bangladesh. I think that artists failed to understand the larger political consequences.”

At the moment, Nepal has a Film Censor Board, there are no such other censorship boards for fields of art, literature or music. The last thing artists want is a censorship board for the arts. Artists believe that signing the document gives reasons to WHF and other groups to censor art, in the future. It appears as if the art community has given in and lost the debate.

Criticisms are now being thrown at both Harijan and Thapa as well as to the Nepal Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA), which is the government body for fine arts in Nepal. NAFA, to their own embarrassment, stayed quiet the whole time. Harijan is now staying away from the conversation altogether, while Thapa has decided to completely shut down the gallery after March 2013.

“If the artists are saying such things then why should I run the gallery?” she reasoned. This decision comes as major throwback to artist and as sad news to contemporary Nepali arts. Siddhartha Art Gallery was opened by Thapa in 1987. It is one of the oldest running galleries of Nepal and has contributed immensely to the arts.

Amidst the bewilderment, a group of artists are still going forward with their campaign for freedom of expression. “We have been already been given the freedom of expression as a part of our basic human rights and we should be able to freely exercise the right,” said artist Ranjit. “We are going to work for the awareness of our rights by holding lectures, discussions and workshops. We also need to learn how to approach such situations in the future.”

“This incident had the potential to strengthen the arts in Nepal but it has ended on a bitter note,” shared Sujan Chitrakar, who was also one of the forerunners in campaign for Harijan and the Gallery. “Shutting down the gallery just like that, after 25 years, is very childish.”

Chitrakar is also the Academic Program Coordinator at KUarts, where Harijan was his student.

“In the future, an artist should only create controversial works if he/she has the conviction to articulate what it is about,” he stated in a serious tone. “That person should be able to take responsibility of the work or should not make such works at all.”

Reproduced by permission. Copyright © 2012 Freemuse.

Kanchan G. Burathoki is an independent artist and freelance art journalist based in Kathmandu, Nepal. She has been writing on art in Nepal since 2009 and is currently the Contributing Arts Editor for Republica English Daily. She is an Art Studio graduate of Mount Holyoke College, USA.