April 30, 2015

Politics of Collectivity: Muralism and Public Space in the Practices of the Brigada Ramona Parra during the Unidad Popular[1]

Written by Florencia San Martin

During the rise of the Chilean Left in the 60s, important public art organizations emerged that revolutionized strategies for political propaganda. Created in 1968 at the 6th Congress of the Communist Youth of Chile (JJ.CC), the Brigada Ramona Parra (BRP) was arguably the most remarkable of these organizations, as its members re-imagined the limits of public space through contingent muralism composed of written slogans. Yet, in the climate of a highly ideological society, the BRP was not an exception to developing radical contradictions in its modes of production, organization, and collectivity. In this paper, I first explore the paradoxes within the BRP after Salvador Allende’s presidential election on September 4, 1969, by analyzing its contingency policies in relationship to the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte (CADA), an art group active in the late 70s and early 80s. Second, I investigate why and how the BRP, beyond its internal paradoxes, re-signified public space as gendered and open, implicating the participation of women in the country’s social and political demands.

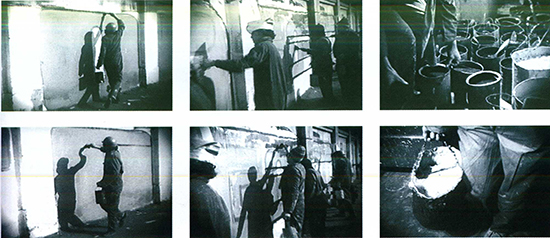

A key event in the history of the BRP took place on September 6, 1969, when roughly 2000 brigadistas marched from Valparaiso to Santiago and created striped murals along the way in response to U.S intervention in the Vietnam War. Hereinafter, the BRP became a coordinated group, creating a central committee in Santiago and eventually about 150 regional segments and local chapters throughout Chile. Composed of 8 to 10 students, militants, workers, and peasants, each brigade was divided into trazadores and rellenadores, that is, tracers of letters that formed words and those who filled the outlines (Plate 1). While the outline was to be black and the interior was to be blue, the background was, in fact, normally yellow and the letters black, as the low cost of these paint colors made them more available. Rejecting any attempt at experimental or crafty techniques, the slogans were made by rapid one color brushwork during the night, which emphasized the political contingency of the muralists’ efforts. As cultural critic Nestor García Canclini argues, “a striped mural could be covered and repainted shortly after with a more adequate theme according the necessities of the time, representing the ongoing change of the political discourse.”[2] Canclini has also called attention to the differences between BRP’s and Mexican muralism. As he states, “the BRP did not fall into the excessive rhetoric of Mexican muralism; it did not strive for the consecration of history, but rather to meet the process, follow its time.”[3] Thus, rather than representing allegorical figures and historical heroes in the pursuit of a national identity, as in the case of Mexican muralism, the BRP sought a project of contingency in their cultural revolution. Yet, despite of his bright analysis, Canclini ignores the aesthetic judgment implemented by the BRP with the institutionalization of the Chilean Left.

With Allende in office, the BRP started to represent the Popular Unity’s victory through timeless iconography. By means of colorful stars, flowers, fists, hands, faces, and doves, the group expressed the ‘happiness’ of the new times (Plate 2). Operating publicly and supported by the State, the BRP’s practices shifted from the hidden and prohibited to the exposed and allowed. In other words, they moved from clandestine striped muralism produced by voiceless actors demanding collective needs, to mural painting in broad daylight produced by victorious political voices. In this context, the cultural program of the Popular Unity, known as La Nueva Cultura (The New Culture), began to commission murals by the BRP to communicate the State’s achievements.[4] Hence, rellenadores started to use blue, red, and white paint to fill the letters in the murals, mirroring the colors of the Chilean flag and, thus, producing highly nationalistic images. As Ana Longoni argues,

The transition from the political realm to artsy muralism represents the aesthetic perspective that was legitimized by the cultural agents and artists of the Popular Unity. Hereinafter, the BRP was seen as part of the art world and, therefore, conceived as a formerly strict political tool that became aestheticized.[5]

Following Longoni’s argument, we might wonder if the New Culture, with its ahistorical symbols of doves and stars, was a unifying program radically different from the former political contingency of the BRP. While the 1969 triumph of the left wing, socialist, and communist political parties silenced transgressive voices, some continued their projects of contingency. As Diamela Eltit has lucidly argued, “while in the early 70s the Communist party turned itself aristocratic and nerudiano, the Other Communist Party continued its active program, that was brigadista, anonymous, and collective.”[6] Consequently, many of the Other Communist Party murals were not photographed and because of this have been forgotten, yet their very absence means their contingency, which denies the signature, the aesthetic value, and the artist's commemoration. In contrast, this lack of conservation did not happen to murals made by artists who, attracted by the New Cultural policy, enthusiastically joined the BRP. Such was the case of Roberto Matta, who in 1971 and in collaboration with the BRP, made a 25-meter long mural at the public pool of La Granja, a low-income commune in Santiago. Entitled The First Goal of the Chilean People, the mural features timeless and amorphous human-like nude figures that interact with each other through speech bubbles that say “vida” (life), and “a vencer!” (To beat!). Commissioned to commemorate Allende’s first year in office, the mural, unlike the BRP’s original policy to “repaint over” a mural, remained untouchable until the coup in 1973, when it was covered with 16 layers of paintings by the military. More than thirty years later, the mural went through a two-year restoration process, which was documented in a film called, The last goal of Matta. The same policy of “non-repaint over” happened in relationship to a 450-meter mural made in 1972 on the banks of the Mapocho River. Executed by the BRP in conjunction with so-called committed artists such as José Balmes, Gracia Barrios, and Francisco Brugnoli, the mural’s aim was to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Chilean Communist Party. Extended from the Puente Loreto to Puente Purísima, it simultaneously narrates stories of the Communist Party and the labor movement in Chile, depicting political leaders interviewing figures of pobladores and workers, which mirrors the narrative of Mexican muralism.

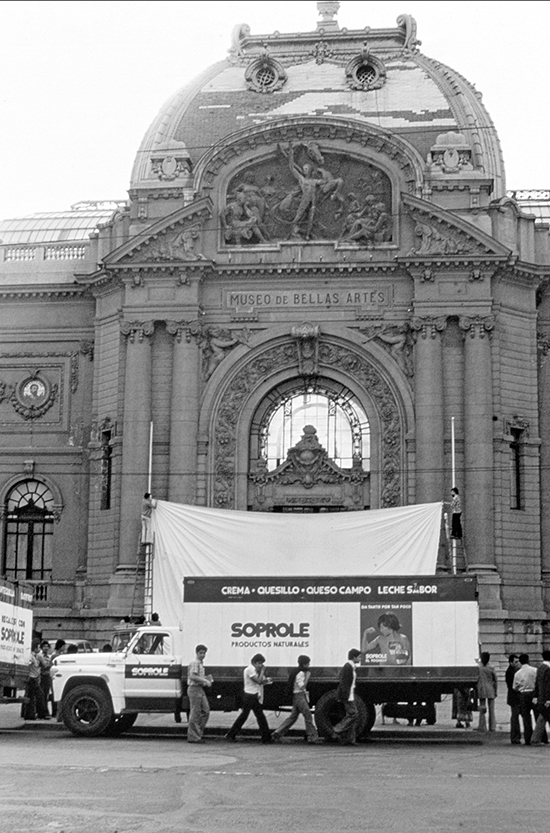

Upon the implementation of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in 1973, the notions of collectivity and ephemerality addressed originally by the BRP reappeared in the work of the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte (CADA).[7] An interdisciplinary group of five artists established in 1979, CADA’s first set of actions, Not to Die of Hunger in Art, used milk as a point of departure to address hunger and lack. The progressive public installations included milk delivery records to a peripheral shantytown; a poem-like statement about the right to milk in Revista Hoy; an art exhibition composed of 100 milk containers in an acrylic box; six empty milk delivery trucks parked for a few hours in front of the Museo de Bellas Artes; and covering the entire entrance of the museum with a large white fabric (Plate 3). While CADA criticized the lack of freedom of expression during Pinochet’s regime through this series, which ended by covering the entrance to Bellas Artes, “it also retook,” as Eltit reminds us, “the sign of milk that was typical of the protests by the Popular Unity; a sign that already represented the condemnation of food restriction since the late 60s.”[8] As Eltit also mentions in another place,

The BRP had and, in my opinion, continues to have, a relationship, although not of a linear character, with CADA. I am referring to connections such as the collective character, the occupation of the city, and the defined and definitive politicization of their signs. Clearly, their artistic operations were different and, in some ways, they might even be considered as divergent, but from another perspective there is a thread–– the inexorable thread of desire–– which, in a fragmentary and nomadic way, related CADA with the BRP, the previous artistic-political occupation of the city.[9]

Chilean cultural critic Nelly Richard, however, disagrees with Eltit’s argument. According to Richard,

The BRP failed to transform the relationship that makes art independent from the force of the political and social organization, for it persisted in a tradition of realism that illustratively subordinates the image to ideological messages. [In the BRP] the wall replaces the frame to portray–– in a monumental way–– the popular national epic through pre-coded figures of the people and the revolution, thematicizing a social imaginary that has been predefined by the program of the State.[10]

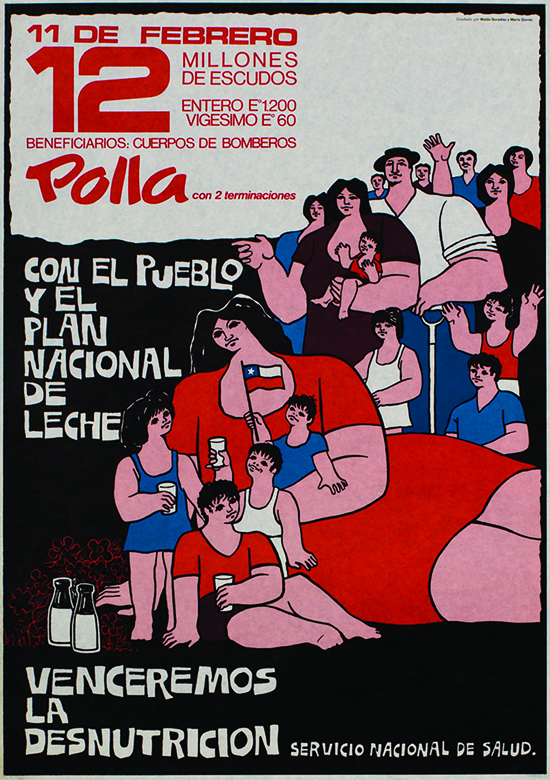

Considering Para no morir de hambre en el arte, Richard not only denies the connections between the BRP and CADA in relationship to the instability in the public space, but she also ignores the way was used in both groups in historical terms. One of the core policies established during Allende’s presidency was the daily distribution of a pint of milk for every child under the age of 15 regardless their socioeconomic situation. Allende’s main slogan for this project, “Children are born to be happy: milk for all,” was advertised by different means throughout the country. Through social realist language, the aesthetics and politics of these propaganda images were indebted to Cuban posters and to the idea of national identity learned from Mexican muralism (Plate 4). With this in mind, when Eltit refers to CADA’s use of milk, she is clearly not citing Allende’s milk campaign–– Eltit literally says, “protests… [of] the late 60s” (see the aforementioned quote). Nevertheless, the date of the single BRP document in which milk demand is depicted provides us a pivotal clue for this paper, which, although enlightenedly mentioned by Eltit, is not proved through images. As the document is dated in 1972, it could also help us to better understand the presence of the Other Communist Party during, and not just before, the government of the Popular Unity. Its visual features demonstrate this point: the use of text instead of iconographic and timeless images on the one hand, and the use of black and yellow paint instead of the colors of the Chilean flag on the other, attest to the presence of striped muralism after the institutionalization of the Left (Plate 5). Hence, in this mural, the sign of milk departs from its common associations to explore the feminine and the maternal, and in this way differs from the posters utilized by the New Culture. In other words, the simple reproduction of the State's main slogan through text, a strategy that conceptualism knows very well, neither calls attention to the Popular Unity's triumph nor to the association between milk and maternity, but rather to the unstable and agitated political climate in 1972 when capitalist sectors supported by the CIA began to restrict Allende's social policies. Women, as potential mothers, are represented in this striped mural as women who, at the same time, are active citizens within public space.[11]

In the wide range of brigades that emerged in the late 60s, the male martyr was always the one to be honored. Such was the case of the Brigada Hernán Mery (from the Christian Democratic Party) and the Brigada Roberto Matus (from the Fatherland and Liberty Nationalist Front). In the Socialist Party, two brigades were the most notorious: Brigada Elmo Catelán (BEC) and Brigada Inti Peredo (BIP). While the former honored a Chilean journalist murdered in Cochabamba in June 1970, the latter honored a Bolivian Marxist who died in La Paz by lethal injection in 1969. The communist Brigada Ramona Parra, on the contrary, took its name from a 20-year-old woman that died not in an international but in a local context during the Slaughter of Plaza Bulnes in 1946.

Due to the strike of the Mapocho and Humberstone Saltpeter miners in 1946, the then president of Chile, Alfredo Duhalde, shut down the legal representation of labor unions, which attacked crucial rights won by laborers in the preceding decades. In solidarity, the Confederation of Workers of Chile (CTCH) held simultaneous strikes throughout the country, with the largest in Santiago on January 28th in which ten thousand people gathered in the Plaza Bulnes. Monitored by 300 police officers, a gun suddenly went off, and so the police opened fire on the crowd brutally injuring many and eventually killing six protesters, among them Ramona Parra.

If one considers that most of the protesters were men, which shows the unions’ overrepresentation of the male subject, and that five of the six victims were men as well, selecting the only woman that died at Plaza Bulnes is significant for two reasons: first, it is a response to both the police records and the press that underestimated the participation of women at the slaughter even though testimonies by family and also articles published by the communist paper, El Siglo, had reported on these details; and second, the memory of Ramona Parra goes beyond the narrow limits of honoring a single fighter, as the selection of the historically excluded female subject constitutes an act of resistance that interferes with what hegemonic history has conceived as a masculinist space.[12] Richard, in an essay published in 2000, explains the difference between the individual, the feminine, and the emotional on the one hand; and the collective, the masculine, and the problems of the Nation on the other.[13] This distinction, I argue, is altered by the BRP’s assertion of the female subject as the one that interferes, by means of contingent political texts, with the codes of the city. In the same essay, Richard demonstrates how other protests, such as Madres de la Plaza de Mayo in Argentina and El Cazerolazo in Chile, transgressed the masculine discourse of the 60s and 70s which separated the domestic from the public and the familial from the citizen. Yet, it is worth asking how the BRP, a coed group that did not operate specifically through female imagery but through the anonymous citizen, altered the historical juncture between public space and masculinity so as to allow for gender difference in the urban environment.

Luis Camnitzer’s brilliant study on Conceptualism in Latin American includes interventions that range from the Tupamaros, the left-wing Uruguayan urban guerrilla that was active during the 60s and 70s, to more internationally informed avant-garde artists that have experimented with mass-communication media.[14] Nonetheless, the BRP (at least its side of political contingency), is not mentioned in the book, which is surprising given the core value that Camnitzer attributes to ethics, agitation, contingency, and information. Certainly, I think, Richard’s fame in Latin American intellectual circles has influenced more than one critic and art historian. Yet, the work of Canclini in the late 70s and, more recently, the invaluable contributions of Eltit and Longoni, have already seeded a path to a more expanded analysis on the BRP. In this paper, I contribute to this path through an analysis of gender, which I argue influenced the radical difference between stripe muralism and mural painting during the unstable and agitated context of Chile’s Popular Unity.

Florencia San Martín is a third year PhD candidate in art history at Rutgers University, where she studies photography and contemporary art, specifically as it relates to post-capitalism in Latin America and the relationships between art and politics in a broader way, considering violence, human rights, and memory.

NOTES

[1] The Unidad Popular (Popular Unity) was a coalition formed in 1969 by left wing political parties in Chile. Being its aim the successful candidacy of Salvador Allende for the 1970 Chilean presidential election, it was composed of the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, the Radical Party, the Social Democratic Party, the Independent Popular Action Party, and Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitario (MAPU).

[2] García Canclini, Nestor. Arte Popular y Sociedad en América Latina (México: Grijalbo, 1977), 73

[3] García Canclini, 205. Translation by the author.

[4] Ana Longoni, “Brigadas Muralistas: La persistencia de una práctica de comunicación político-visual,” Revista de Crítica Cultural, 19 (1999)

[5] Ibid, 26. Translation by the author.

[6] Diamela Eltit, in Galende, Federico. Filtraciones I (Santiago: Ediatorial ARCIS – Cuarto Propio), 221

[7] Active from 1979 through 1984, CADA was form by poet Raúl Zurita, writer Diamela Eltit, visual artists Juan Castillo and Lotty Rosenfeld, and sociologist Fernando Ballcels.

[8] Diamela Eltit, in Galende, Federico. Filtraciones I (Santiago: Ediatorial ARCIS – Cuarto Propio), 221

[9] Eltit, Diamela. Emergencias. Escritos sobre Literatura, Arte y Política (Santiago: Planeta, 2000) 161-162. Translation by the author.

[10] Richard, Nelly. Márgenes e Instituciones, Arte en Chile desde 1973 (Santiago: Metales Pesados, 2006), 64. Translation by the author.

[11] I am grateful to Dr. Ana María Reyes, from the department of History of Art and Architecture at Boston University, for her comment on the relationship between milk, women, and the State during this period in Chile when this paper was presented at the 3131st Annual Boston University Graduate Symposium on the History of Art and Architecture, on February 28th, 2015

[12] For more information about this subject, see Alfonso Salgado, “La familia de Ramona Parra en la Plaza Bulnes: Una aproximación de género a la militancia política, la protesta social y la violencia estatal en el Chile del siglo veinte” Universidad de Santiago, 18 (2014)

[13] Nelly Richard, “Protestas Callejeras y Símbolos Domésticos”. Revista de Crítica Cultural 21, (2000): 159

[14] See Camnitzer, Luis. Conceptualism in Latin America: Didactics of Liberation (University of Texas Press, 2007)