A Loud Silence: An Interview with Tada Hengsapkul on Art and Democracy in Thailand Today

Written by Roger Nelson

Tada Hengsapkul (born 1987 in Korat, Thailand) is an artist based in Bangkok. Trained in photography at Bangkok’s Pohchang Academy of Arts, he has been exhibiting in Thailand since 2009, and internationally since 2011, including in The 2nd Chongqing Biennale for Young Artists (China, 2011), and at Singapore’s Sundaram Tagore Gallery (2013). Announcements of his participation in other regional biennales will be forthcoming.

In 2017, Tada held two solo exhibitions in Thailand. The first, at Chiang Mai’s Gallery Seescape, was titled The Things That Take Us Apart, and centred on playful and theatrical video images of a group of strangers dancing, often naked, in a moment of hedonistic escape from the increasingly restricted experience of daily life since the 2014 coup d’etat, which reinstated military rule in the officially democratic Southeast Asian nation. Tada’s process for this project—which involved calling for volunteers, orchestrating informal dance classes for them, and then filming the results in a kind of insider-observer role (with the artist often appearing within the frame of the final video image)—combined a participatory approach with a highly aestheticized approach to videography. These may be considered twin hallmarks of artists of Tada’s generation in this region.

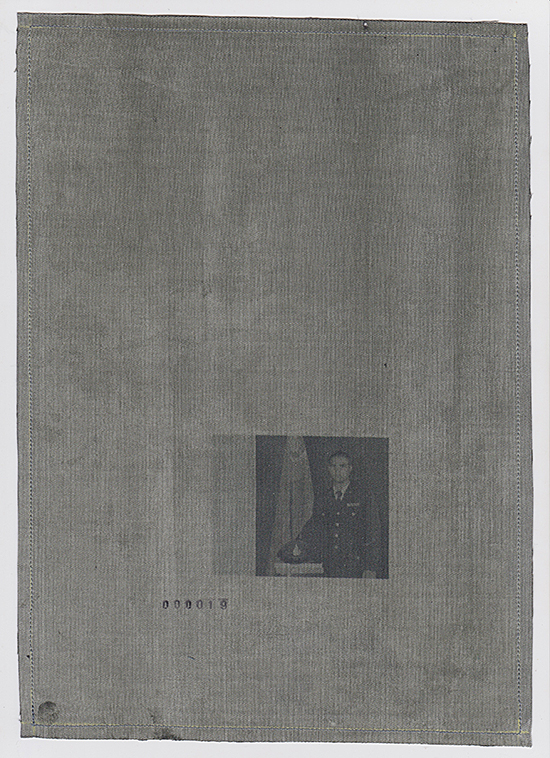

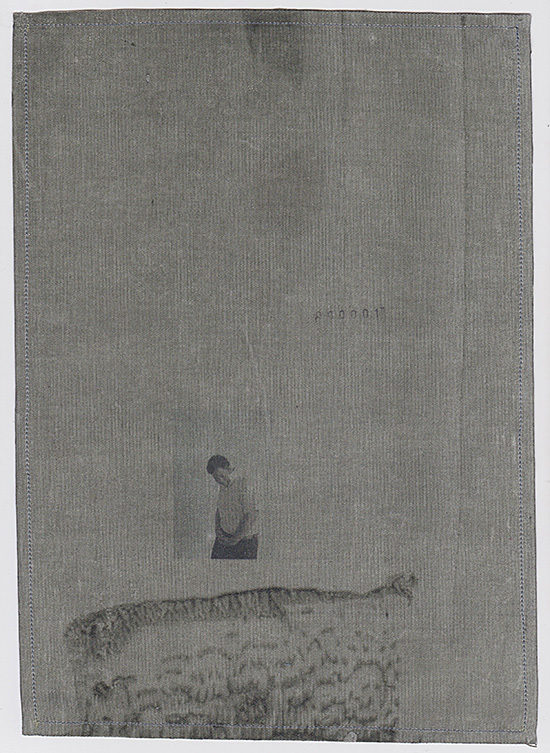

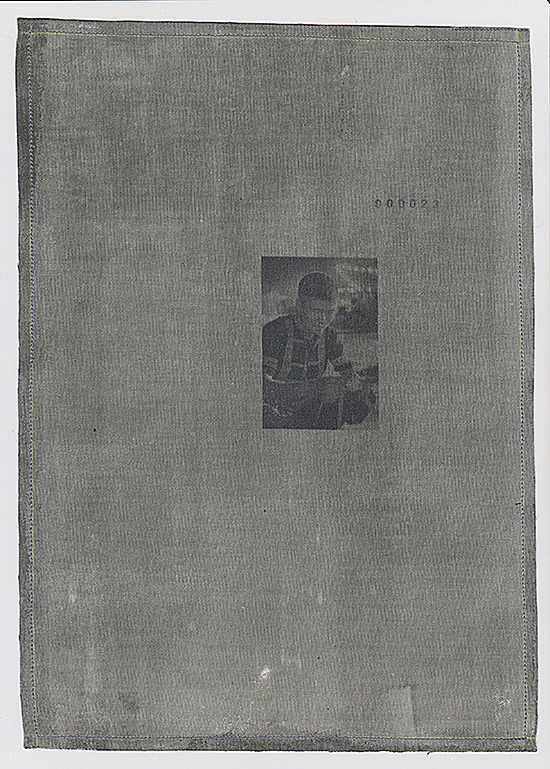

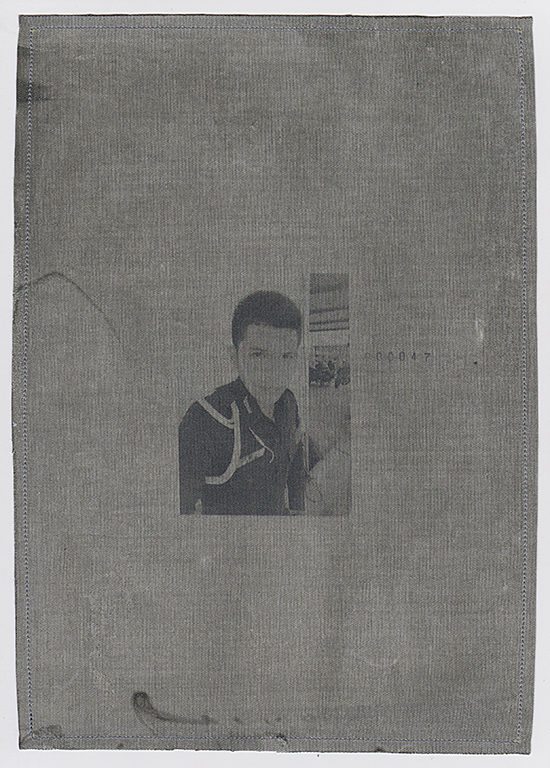

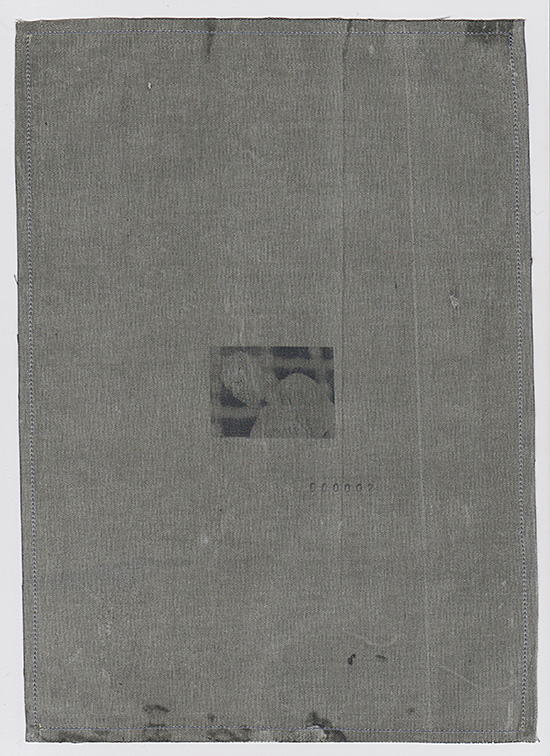

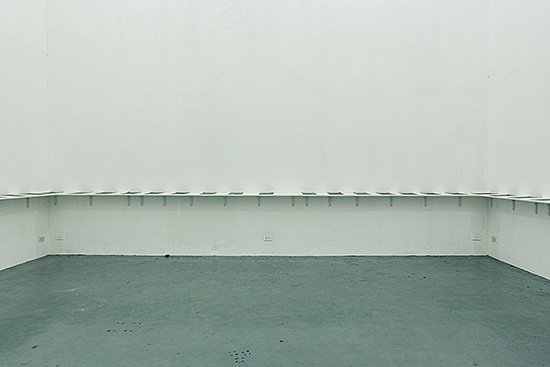

Tada’s second solo exhibition of 2017, at Bangkok’s Cartel Artspace, was an interactive installation titled The Shards Would Shatter at Touch. In a white cube space, on a white shelf installed at waist height, the artist presented forty pieces of cloth painted with black thermochromic paint. Visitors were invited to touch these, and hold them to their chests. The heat of the visitor’s body caused the black cloth to change colour, and an image to appear: a portrait of one of Thailand’s many political prisoners, past and present. Further information about these activists was provided in accompanying text within the gallery space, which drew from various online activist and other sources. The artist remediated this data by facilitating an empathic bodily embrace.

Hundreds of people attended the exhibition opening, and it generated an active and at times heated response from both artists and activists, writing in online forums, mostly in Thai, and also in English. It was also reviewed in the leading English-language national newspaper. The exhibition was later re-presented at Art Stage Singapore, one of Southeast Asia’s longest-running contemporary art fairs, in January 2018. By these measures, the exhibition was a success. However, it was also closed early due to political pressure. By this measure, the Thai military government’s regime of unpredictable yet intimidating censorship was also successful.

This conversation thus begins with a reflection on this project.

Roger Nelson: On 15 June 2017, five soldiers visited your exhibition, The Shards Would Shatter at Touch, which had opened at Cartel Artspace in Bangkok earlier that month. The exhibition was closed at the time of their visit. Hearing of their attempt to enter, you arranged for all the work to be removed from the gallery, closing the exhibition the week before it was scheduled to end. Other artists exhibiting in the same gallery district were not so lucky; three photographs in Harit Srikhao’s exhibition next door at Gallery Ver were removed by the military. In a climate of increasing clampdown on political dissent in Thailand, these events were not surprising.

In this interview, I’d like to invite you to reflect on the power of your artistic practice, in the face of the power of the military junta’s censorship. Conversations we’ve had over the past several years make me imagine that this will also require us to reflect not only on power, but also on powerlessness: thinking about the limits to what artistic practice can achieve, and the limits to the ruling regime’s control.

What did you aim to achieve with the exhibition The Shards Would Shatter at Touch? How would you compare your power and your success, as an artist, with the power and success of the censors?

Tada Hengsapkul: Now Thailand has a crisis about controlling the large amount of people who have come out to claim rights and liberties, following the call of democracy, after the 13th coup d’etat led by General Prayut Chan-o-cha. After the coup, various groups of activists had to sign the government’s Memorandum of Understanding on Reconciliation. The stage of free expression has been suspended, or some stages of expression have been only awkwardly and partially observed. People have been jailed because the lèse-majesté law (Thai Criminal Code section 112), some only because of mistakes. Other people have been put in jail for no reason by the power of the dictatorship.

However, I saw that there is one more stage of expression that the dictatorship hadn’t yet reached. It’s the art stage, in the white cube. I thought about how to make people who were exploited, who were sent to jail, who didn’t get justice until their deaths, reveal themselves in this stage of expression, and put forward their stories, their sad biographies to a group of people that come around in this white cube. To know how things have been going.

If you ask about how artists have power when compared to the power of the censors, I would say that artists hardly have any power. Because in Thailand, artists don't have that much power when compared to activists, but still, art is a very interesting tool.

What artists can do is go forward alongside with others. What impressed me about the event when the soldiers visited the galleries in June 2017 was that when the news was published by BBC Thai, I found a lot of comments [online] criticizing the act of the soliders. I think what happened damaged the state of expression in art, but it brought a wave to society.

I hope in the future, there will be a lot of Thai artists who are more provocative with the soldiers. But this path is quite difficult. Because we're indoctrinated to live in fear, fear of what we can’t predict. Especially with the dictatorship, there is no way to limit their power.

Roger: You mentioned that what an artist can do is “go forward alongside with others.” Who is alongside you? Who are you alongside? Can you talk about your collaborations, with artists, activists, filmmakers, musicians, and other people? What kinds of research you do to make your work, and to find your freedom?

Tada: I’m alongside with people who are interested in democracy, who respect human rights, who believe in the future, who dream about freedom, and people who dare to change. About collaborations, for me, it’s not a collaboration to create art together. Instead it is a collaboration to connect, and create a balance in society. Imagine if society didn’t have artists. It would be a very strange society. Because in history, humanity has been associated with art since ancient times.

My research is to live in a different way, to not stick to the same. It’s to face problems and to learn from mistakes, to see other people, listen to other people, open your mind, smile if you want to, laugh if it’s okay to laugh. Love if it’s okay to be loved. Hate if something is disgusting. There’s no wrong, no right. Just do everything from an open mind. And this is how I research.

Roger: Expanding from your own experience of censorship with The Shards Will Shatter at Touch, can you comment more broadly on censorship and art in Thailand (and in Southeast Asia, if you like)? You said that you hope that in future more Thai artists will be provocative with the soldiers, but that the path is quite difficult. Can you give some examples of other artists or other people who inspire you to take this path?

Tada: From the day that the soldiers came to close the exhibition until now, they still come to visit and observe at the gallery from time to time. It makes the people who work there feel anxious, and fear what might happen. Last month, the graffiti artist named Headache Stencil created his work in public space. It was a picture of a clock, a sarcastic reference to [Defence Minister] Prawit Wongsuwan. This work has been erased, and the artist has been called by the government. Since then, graffiti artists have started to make political art more and more, but these have all been erased too.

What is happening in Thailand now makes me think about the crisis situation in Vietnam. The art censorship there is very strict. It affects the galleries, not only the artists. If an artist wants to show their work, they have to send a proposal to the government. The government will ask the artist about the metaphors in the work, and they will say if it passes or not [to be granted an exhibition license]. Before the exhibition, they will send someone to watch. If it has people from the black-list there, they will make an appointment every month to talk about political attitudes. What has happened is damaging the creativity. The artists have been tied down, and galleries have been closed. Artists don’t have a stage to express their thoughts.

One artist who inspired me to take this path is the Voina art group, from Russia. When I think of them, it encourages me to create art, no matter how hard it is.

Roger: This issue of Seismopolite is titled “Art and Freedom of Expression.” What does this term mean to you, in the context in which you work?

For me, art is a key to the door of understanding human existence. And it is a tool to show reality in a variety of angles: not just empirical, but abstract, through a questioning of everyday life. Therefore, art can freely question and answer about everything. Art often hides things. Whether it is in our body, clothing, daily life, water, family, education, chair, past, future, present, government, domination, state, nationality, sex, gender, love, hate, universe, poverty, communism, goodness, badness, democracy, dictatorship, art, animal, technology, plants, tears, laughter, convenience, colour, white, grey, black, movement, standstill, artificial intelligence, King, environment, religion, loudness, quietness. Everything in the world should be dissected and investigated in any possible way. and freely in every step, to see how truly is its beauty and its existence. Even though the questioning and answering of some things is against morality in some areas, an artist shouldn’t surrender.

Because if our mouth has been shut and we let our mouth be shut, it means that we can’t kiss the one we love honestly. Art should break through the hand that keeps our mouth shut. And when art gets free from obscurity, it will bring us to the awaiting future: the future world that has been told through art in the past and in the present.

This work, The Shards Would Shatter at Touch, is just a fragment of what I have explained above. But this fragment needs a world; it needs its friends to understand that what they do is not evil. They all dream about peace and about the future of the world. Also about the sweetness that people in my country never taste: democracy. People have been frozen in a state of drowning in the darkness, at the border that is created by the dictatorship’s thought. I can’t see anything there except the cold, quiet darkness.

Roger: Do you regard your artistic practice as, at least in part, a tool of dialogue, or of resolving conflict? How does it differ, in strategy or in effect, from other kinds of dialogue and conflict resolution?

To me, art is a tool that is glazed with hope: hope that the conflict in society will be solved, and hope that people will understand about the differences among humankind. I am one of the little people: I am not special, I am like any other human.

But art is different from other tools of dialogue and ways of resolving conflict. I would say art is a mirror in front of you: it’s designed to reflect different kinds of shape and colour. You will see yourself through that. You will listen to the voice inside yourself. You will hear a loud silence. It’ll be louder and louder. You will learn things through that mirror with yourself. And you will have a moment of freedom in front of that mirror. After that, you may want to embrace yourself or ignore yourself, it’s all your right. But at least, art brings you to the state of self-consciousness through the mirror. That state of self-consciousness is called art. And art will bring you to a future world that everyone has dreamed of.

* * *

Roger Nelson is an art historian and independent curator, and Postdoctoral Fellow at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His PhD was on concepts of modernity and contemporaneity in “Cambodian Arts” during the 20th and 21st centuries, and he is presently investigating relationships between images, texts, urban spaces and curatorial practices, with a particular focus on mainland Southeast Asia. Roger is co-founding co-editor of the journal Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia (NUS Press), and his translation of Suon Sorin’s 1961 Khmer novel A New Sun Rises Over the Old Land is forthcoming with NUS Press. His most recent curatorial project was People, Money, Ghosts (Movement as Metaphor), an exhibition and lecture series at Bangkok’s Jim Thompson Art Centre.