July 6, 2014

Photography and propaganda in Yugoslavia after WW2

Written by Milanka Todić

The agitprop culture lasted in Yugoslavia from 1945 to 1952. This was the beginning of the communist era and the biggest political crisis following the break with Stalin in 1948. Immediately after the end of the WW2, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia set up an “agitation and propaganda apparatus”.[1] It had numerous and very diverse tasks: from organizing cultural life in towns and villages, monitoring work at universities and planning theater repertoires, to reading of everyday cultural columns in the press. Already its very name, “apparatus”, taken over from the rhetoric of industrial society and its belief in technical progress, was inappropriate to the actual circumstances in Yugoslavia where people mostly lived in rural areas. But “apparatuses”, in terms of machines, was glorified in avant-garde circles as well. There, the new aesthetics of the machine was intended to radically reform the overall habits of both representation and perception of the common lifestyle.

The meta-language of agitation and propaganda remained an enduring part of the ideological monopoly of the Communist Party and was imported together with the entire Stalinist culture concept. This ideology was, with minor variations, present throughout the cultural space “behind the Iron Curtain.” As in other countries called people’s democracies, the Yugoslav communists had only to “properly apply” the totalitarian model of society from USSR, which prescribed that socialist realism was the only acceptable model of art for the entire communist society.

Socialist realism insisted on an extremely restricted choice of motifs and a strictly canonized iconography. But opposite to that aesthetic restriction, the work of art could be the carrier of an amplified ideological meaning of “politicality”. The society that inaugurated institutions of censorship and mass media control could leave nothing to the spontaneous creativity of the artist. In the monumental project of creating the aesthetics of the new political system, photography had a prominent role, second only to film. Writing about photography, contemporaries claimed that it was not enough if it “showed chimneys and wheel-barrows”, it was necessary that it “expressed the image of the new man, the builder of socialism, the image of a man creating great works in our country and elevating, bringing up and ennobling himself through the creation of such works”.[2]

The principal features of the new man were outlined way back in the circles of avant-garde artistic groups in USSR. In the context of the totalitarian regimes before the WW2, the new man was seen as a mythical hero capable of performing grandiose labors to the benefit of the entire community. The utopist image of the new man, as the universal cultural cliché, was reproduced and moved from Stalin’s to Tito’s dictatorship, and concerned anything from literature to sculpture, from theoretical texts to news reports, even photography and money.

Appropriations the Bolshevik ideological and visual rhetoric

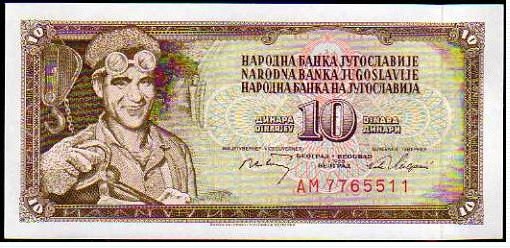

What is believed to be the original photograph of the famous shock-worker Alija Sirotanović, taken by Nikola Bibić, a reporter of the Borba (Battle) daily, is far better known as a technical reproduction on a banknote than a work of art. That photograph, that is, its widely circulated copies, belongs undoubtedly to the opus of mass representations where the hero of the new Yugoslav community acquires concrete visual form. In the process of constructing the myth of the new and young hero, facts such as the hero’s true identity are transformed or made redundant and simply rejected. This picture is a perfect example of the mass spectacle of pictures of the new man who “creates great works”. It gained such popularity precisely because it follows the established scenario and typology of the hero in totalitarianism. First of all it is a picture of a young and strong young miner.

A lot has been said about cult of youth and its symbolic and archetypal role in totalitarianism. But it is very important to know here that the mythical properties of the young hero are standardized. They were the norm in the aesthetic of communism as they, above all, postulate the key ideal of the future community. However, the image of the hero of Yugoslav socialist development was constructed by the Party following the model of the Soviet typology of the miner – shock-worker Alexey Stakhanov who gave name to an entire labor movement founded in 1935.[3]

It is interesting to note that in the process of reproduction, the Yugoslav copy of the Soviet model-hero retained the same initials: A.S. Alexey Stakhanov and Alija Sirotanović would be equal as young shock-workers, and ultimately, the correct solution to the puzzle would be Soviet Union = Yugoslavia in the context of political rhetoric and advertisement of new ideology.

The picture of the young miner and shock-worker survived the dictatorship of the proletariat in which even prominent leaders of the revolution and communist party fell from grace and vanished from the political scene, partly because of the fact that it was visual evidence of the basic utopist idea of the new man of communism. One can even say that this most popular Yugoslav mythical young hero died together with the collective concept of the new man – the banknote with the photograph of the miner Alija Sirotanović was officially withdrawn from circulation on December 31st 1989. In the 1990s the socialist Yugoslavia, or “Tito’s Yugoslavia”, as many in the West called it, was undergoing a dramatic break-up.

Appropriations of the Hollywood rhetoric in agitprop photography

The first and greatest mythical hero and moral ideal of the entire Yugoslav community, was Josip Broz Tito, who was always everyone’s comrade. All inhabitants of Yugoslavia, from fabric workers to pupils, teachers and cooperative members, for years and decades, spent every moment of their working hours under the vigilant eye of comrade Tito. Every kindergarten, classroom, office, factory, official premises and institution had to have large photographs of him showcased on the central wall and next to the ceiling.

Although many of these photographs were signed by George Skrigin (1910-1997), an outstanding photographer, and were representative portraits of a ruler, they lacked the traditional aura of a work of art. First of all, they could be reproduced in infinite number because they were cheap photos. It is not all that easy to answer with a simple “yes” or “no” to the question whether this, in Benjamin’s age of mechanical reproduction of a work of art, caused the ruler himself to lose some of his charismatic aura. However, we can say that the photograph quantitatively increases the charisma of the leader in the age of agitprop culture. Thanks to the omnipresence of Tito’s portrait photography the cult of the leader was constructed around his status as both the President of the communist state and President of the Communist Party.

Compared to sculptures of kings, it was easier and faster for Tito’s pictures to make their way into every public space: from a tiny janitor’s booth to a congress hall. Photography greatly promotes the old rituals and tactics of spreading the cult of the ruler, but the suggestiveness of a monumental memorial that is the privilege of a three-dimensional object, is lost. But, again, the omnipresent Tito’s portrait photograph carries the same message as the official portraits or sculptures of old rulers which traditionally marked institutions of power. Finally, Tito’s appearance in the representative marshal’s military uniform stressed his Partisan authority many years after WW2.

However, I shall underline that the visual matrix of the art of socialist realism, including photography, was not prescribed by either the Yugoslav Communist Party or the working class, or by the popular masses. It was imposed as a ready-made model of representation and was an integral part of the imported soviet totalitarian culture. On the other side, Tito’s portraits from the agitprop era were a testimony of his trajectory from a guerrilla war hero to a Western glamorous personality and political celebrity.

John Phillips, a photographer of Life magazine writes, the Yugoslav leader wore a "dazzling white flannel slacks and a pale blue sport shirt embroidered with the monogram “T”," and then he changed into “a coat and pale peach-colored shirt” with “a polka-dot tie held in place by a heavy gold clip shaped like a scimitar” for the photo shoot in Tito’s Villas on the Adriatic Island of Brioni in 1949.[4] We also learn about the way Tito combs his hair and holds his cigarette-holder, and are lead to admire the amazing color of his Mediterranean tan “which made his white-streaked blond hair seem even lighter in color.[5]

The 1949 Life cover emphasizes Tito’s masculine and stylish appearance, rendering him the embodiment of a political stereotype of the “good-looking chap” whose obvious personal “sex appeal” is properly applied and mediated by the mass media in the same way as in Hollywood’s movies and the very popular cult of mature male movie-stars. “Typified by the male roles played by Humphrey Bogart and Carry Grant, the late forties and fifties gave birth to a type of a mature man as a new sex symbol. He was single and attractive, firm in character, experienced yet adventurous, determined and assertive in action, emotionally stand-offish but warm, always elegantly dressed, with proper manners. Tito’s public image mobilized all of these attributes of the American post-war male ideal, distinguishing him from a stereotypical Stalinist puppet. That is to say, Tito’s good looks also made Titoism an ‘attractive’ alternative to Stalinism,” summarized Nikolina Kurtović in her research dedicated to the Cold War photography.[6]

Photography as communists’ and Hollywood’s political tool

Photographs of strong young workers, constructed the cult of the new man with the portrait of Alia Sirotanović as role model. Images of shock-workers, athletes and spry female are coded representations of an idyllic moral order that belongs to the classless society and to the new man. A critical look at photographs from the first decades of socialism shows that spontaneously “captured” motifs were never a direct manifestation of “real life”. They were, on the contrary, a product of manipulation and simulation of the mass media that was fully controlled by the Party propaganda apparatus. Photography, like the other mass media, was mobilized and employed in order to systematically transform the life of the group and determine the class position of the individual. And that as part of the grandiose utopist project of the new reading of history, of education and re-education communist community.

Finally, we would have to agree with Nikolai Tarabukin’s idea that “Purely naturalistic photography is unusable for advertising” ideology.[7] During agitprop culture the portraits of Josip Broz Tito as guerrilla war leader and unique Yugoslav marshal maintain consistency with the media representations of Hollywood stereotypes in order to increase his political power and serve the Cold-War rhetoric of crumbling communism.

[1] M. Todić, Photography and Propaganda 1945-1958, https://www.academia.edu/1572918/Photography_and_Propaganda_1945-1958

[2] A.D., After the 5th Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, Fotografija, No. 2, Belgrade 1948, 17.

[3] Alexey Stakhanov, a miner in Dombas in agreement with the local Party leadership, dug 102 tons of coal in one day in 1935, which exceeded the usual norm by 14 times. The Yugoslav press wrote that a contest had been organized between the workers of two mines in Bosnia and Herzegovina. “The best work output results were achieved by the brigade of the well-known shock worker Alija Sirotanović, which surpassed the norm by 219%”, Borba, 27 June 1949; Alija Sirotanović who regularly exceeded the quota “surpassed Stakhanov’s first record by 40 tons”, Borba, 29 July 1949. Later, the mass media took over the duty of articulating the hero of labor myth and its original structure was somewhat modified. Thirty years later we could read that “Alija’s brigade exceeded the record held so far by the brigade of the Soviet miner, by 50 tons… To date this record has not been broken, nor, truth to tell, has anyone tried to surpass it”, S. Zvizdić, Alija Sirotanović, Vjesnik, 24 March 1979.

[4] “Life photographer visits with Tito,” Life 27, no. 11 (12 Sept. 1949), 42.

[5] Ibid.

[6] N. Kurtović, Communist Stardom in The Cold War: Josip Broz Tito in Western and Yugoslav Photography, 1943-1980, https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/33814

[7] N. Tarabukin, The Art of the Day, October, No. 93, summer 2000, pp. 76; B. Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism , Avant–Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond , Princeton University Press, New Jersey 1992