July 6, 2014

Eye-snipers

The iconoclastic practice of Tahrir

Written by Mikala Hyldig Dal

Egypt’s revolution of 2011 brought forth one of the most powerful icons of civil dissent in recent times: Tahrir Square occupied by masses of protestors seen from a bird’s eye view. The 2014 image of Tahrir might signify a mode of iconoclasm in which the visuality of the broken icon is intact while its ideological content is subverted.

Preposition

Two images exist within each other:

One depicts a blinded eye; the structure of the cornea has been ruptured by a gunshot. Its surface is uneven, the layers cringe up and inwards. The iris has lost its colours to different shades of white. The eye sees nothing and everything; it is itself the sum of all images ever to have played out in the field of its broken vision.[1]

If we move past the blind stare of the damaged membrane another image emerges:

A public Square occupied by hundreds and thousands of moving bodies, performing an image in and of itself. The Square transforms into a stage; its temporary inhabitants perform their act to an international body of image production. Categories of action, image and representation collide as the protestors simultaneously project, record and screen their own performance.[2] The two images are locked in an iconoclastic circuit in which they absorb, erase, and re-establish each other continuously; the one presupposes the other – neither can exist alone.

Eye-snipers

For the past three years I have conducted research on image politics in transitory Egypt, as a lecturer in the Arts Department of the American University and the Faculty of Applied Sciences and Arts at the German University in Cairo. The reciprocal relationship between authoritarian practices of censorship and various forms of image activism has been a central subject to my research during this time.[3] In certain instances we can observe how political and representational desires merge and coincide with processes of iconoclasm to form an elusive image type that we might call an iconoclastic image; it is the working of this image type that the present essay aims to outline.

In 2011 Tahrir Square became an icon of global protest movements; we might think of the image of the injured eye as its less familiar backside. I found it, among many others, on the hard-disc image-archive of the activist filmmakers group Mosireen Video Collective[4] on Adly Street about five minutes away from Midan Tahrir. The eye belongs to one of the numerous protestors who have lost their eyesight to police snipers during the revolutionary waves sparked by January 25; the term "eye-sniper" signifies the intentional blinding of demonstrators as a means of attacking the visual agency of the protest movement.[5] In their struggle to subvert autocratic power structures and towards a new state building activists found ways to unite visual, political and artistic agency.[6] Since then (shifting) groups of protestors and authorities have been interlocked in a circuit of reciprocal gestures of image-making and breaking.

The targeted blinding of eye-vision can be understood as an indirect result of the political power of the collective image of Tahrir; reversely, Tahrir is an image that is increasingly becoming an instrument to blind its spectators to the authoritarian power structures that emerge from its shadow: The military government is in a process of claiming ownership over the popular revolution of 2011 as a means to reinstate a regime which Tahrir in its original incarnation in 2011 was in direct opposition to.[7] The 2014 image of Tahrir might signify a mode of iconoclasm in which the visuality of the broken icon is intact while its ideological content is subverted.

Processes of erasure in revolutionary Egypt: Monochromizing, blinding, forgetting

We can currently observe three instances of iconoclastic operations in Egypt expressed respectively in the eradication of physical images, in the blinding of biological vision and in a collective process of not-seeing. I have defined these loosely pertaining to their inherent practice and method as:

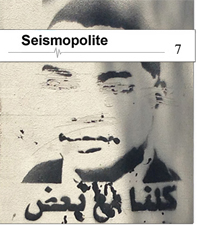

Monochromizing: This form of erasure takes place through the physical painting over of a figurative image or written statement – typically a regime critical graffiti mural – by the use of monochrome paint. This continuous process of erasing-by-painting has covered the streets of Cairo with elaborate colour patches in different tones and geometrical figurations reminiscent, to me, of the art-historical tradition of the monochrome painting; the painted surfaces inherently quote the images they have been placed to cover by inverting these into symbolic representations.

Below the superimposed layers of paint the murals remain intact and are visible wherever the colour has been applied too sparsely; here they turn into ghostly bodies in-between presence and absence. The monochromes on their side often serve as a background for new drawings and thus assume the function of interim canvases in a continuous cycle of binary representational shifts. Sometimes the monochromizing strokes are applied only on the outline of the offensive image leaving out the negative space; here the erasure turns into as an actual second drawing of the original message: the hand of the law enforcer reproduces the gesture of the transgressor.

Blinding: The iconoclastic image can also take form in the visual residue of a process of erasure; this applies to the image of the human eye that has been blinded by an eye-sniper.

On a symbolical level the gesture is turned towards the representation of political power figures on propaganda posters and to commemoration murals of revolutionaries who loose their eyes to the fingernails, pens or spray cans of passers by. The face might be the most sensitive area of representation to a realist painter; it certainly is the most offensive part to any iconoclast; is it not above all the presence if a gaze within an image, a looking back onto the observer from within the image that invokes the feeling that the representation has transgressed into a state of being (and thus challenged the divine powers’ monopoly to create life)? It is at the face and specifically at the eyes that iconoclasts throughout time have directed their main and often their only incision. Historically iconoclasts have conducted symbolic decapitations on anthropomorphic figures simply by drawing a thin line across the throat of the offensive depictions.[8] By the severing of the head from the body one kills the presumed living entity within the image. In this procedure the iconoclast act forms as an essentially symbolic incision, aimed not at the image as such, but at its explicit liveliness; the image body is left intact, but the induction of life is negated by an incision that separates the gaze from the body, and so returns the image into blindness.

Not-seeing: The military’s current visual politics actively discerns between permissible images, namely such that embed its institution in a nationalistic discours,[9] and forbidden images that challenge the same, onto which they pass a taboo. To the latter category belongs an icon such as the “hand of Rabaa",[10] a hand with four outstretched fingers that symbolizes the killing of hundreds of anti-coup protesters at Rabaa Square[11] in Cairo, August 2013. This symbol is omnipresent in the form of drawings, prints and stickers throughout the city’s urban space yet national news outlets refrain from depicting it and public opinion – having been strongly induced by a regime discourse that labels the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization – seems to largely ignore the symbol and what it represents. In this reluctance to acknowledge that which we directly encounter in our visual space we might touch upon a type of iconoclasm that befalls neither the image, nor the representation, but the act of seeing itself; one that forms as a constant real-time editing process that directs the gaze towards certain images and diverts it away from others. This process of not-seeing goes hand in hand with a process of non-remembrance that befalls the country’s recent past, particularly pertaining to the numerous human rights violations that have been and that are continuously being perpetrated by the SCAF (Supreme Council of the Armed Forces) and that were subjected to a critical discourse in late 2011 and in 2012, which has since significantly declined.

The dialectic of the iconoclastic image

During intense transitional phases at times representational and political paradigm shifts coincide with processes of image-breaking to bring forth what we have called the “iconoclastic image”. The paradigmatic iconoclastic image occurs when the process of subverting one icon effectively brings forth another. A line of such images could be drawn from the black cube of the Kaaba in Mecca, Malevich’s painting Black Square from 1923 (emblematic of the outlook of this essay even Malevich’s Ur-Bild of artistic iconoclasm hides beneath its surface another image reality: Cracks in the paint of the Black Square reveal handmade drawings on the bottom layer of the canvas), Ai Weiwei’s falling Dynasty urn, the bombing of Buddhist statues in Afghanistan in March 2001, the loop of the collapsing Twin Towers on Manhattan later that same year, the American flag draped over Saddam Hussein’s statue in Baghdad in April 2003; a story line that comes to a strange collapse in Alfredo Jaar’s May 1, 2011 (2011) that juxtaposes the American president’s long-distance monitoring of the assassination of Osama bin Laden in Pakistan with a monochrome LCD screen and a blank text field.

That iconoclastic dispositions can fertilize the ground for new modes of image production can also be traced in the deep-time image connections between the ornamental image tradition brought forth by 7th century Islamic aniconism and the progression of abstract painting in Europe in the 1800s, a research that the artist-researcher Kaya Behkalam and I pursue in the installation piece Atlas, a commissioned work for the exhibition Istanbul Modern Berlin in Martin Gropius Bau Berlin 2009. We approach the iconoclastic image as an ambiguous field of practice; the image produced here is a tentative one, a mere frame perhaps around a constant process of image-absorption and re-formatting. We might classify such an image as a “cannibal”, in the indigenous sense of the word: it “eats up” (consumes) its opponent, in an act that transfers the strength of the devoured enemy to the consuming body.[12] The occupation with such an elusive image type requires us to assert a gaze that is aware of its own working, with Derrida:

Before doubt ever becomes a system, skepsis has to do with the eyes. The word refers to a visual perception, to the observation, vigilance, and attention of the gaze [regard] during an examination. One is on the lookout, one reflects upon what one sees, reflects what one sees by delaying the moment of conclusion.[13]

The subject of interest here is not the outward appearance of the image in question but instead the inner, co-dependent working of the images that emerge through iconoclash,[14] i.e. a process of iconoclasm that carries visual productivity and social transformation with it.

Gottfried Böhm asserts that every new image destroys or at least re-organizes the frame of reference of the images pre-existing it; image production itself unfolds an immanent iconoclasm.[15] In a similar logic of thought Hannah Arendt describes the very fabric of political participation as an in its essence iconoclastic practice: by applying any type of new political objective in one’s action, one is inadvertently performing an act subversive, even destructive, to the existing order of things.[16] If we accept that the practice of iconoclasm and the practice of political participation share an intrinsic logic in their inner working we might create a frame of thought that connects the two as instances of an essential incision that moves the status quo into a state of transition.

Within such a frame of reference we would be able to find that the point in time in which these two instances become inseparable from each other, indeed merge to a point of no possible differentiation, is the momentum of a paradigm change that is moved simultaneously by political and representational desires.

Jacques Ranciére’s and Hannah Arendt’s theories of the political can serve to focus our attention on the times and places[17] in which such collisions are activated; I will suggest that Egypt today is such a place. The icon of Midan Tahrir might be a good point of departure for us to examine how the dynamics of the performative field of (political) action thus outlined is reflected contemporarily, in the working of an iconoclastic image that too finds itself in a continuous state of becoming, manifesting and equalling out in continuous cycles.

The relevance of the image politics surrounding the Egyptian revolution since 2011 can by no means be limited to their immediate local context; any place so elaborately docked at and feeding into the image reality of global networks today can no longer be treated along the lines of delimited geography.

Tahrir and mimesis/ Strong image, weak space

Since 2011 various groupings, many of them with conflicting interests, have claimed Midan Tahrir as a space to manifest and make visible their causes: The place has been utilized for demonstrations both against and for the Muslim Brotherhood, against and for the SCAF; against Israel and America; for women’s rights and the left opposition. Seen from a bird’s eye view though – its dominant iconographic representation[18] – Tahrir looks the same, and uncomfortably so, regardless of the respective objectives of the protests that occupy its space or the power structures that utilize its symbolic image value for their own ends. The same power structures that were deeply involved in the oppression of the revolutionary movement – at the latest since the massacres in Mohamed Mahmoud street in the winter of 2011 – erected a “Martyr’s Memorial” on Tahrir square in the night of November 19. 2013. There had been no preceding public debate about the nature of the monument, its form, let alone its justification in the present situation. In rejection, perhaps, of a violating institution’s right to mourn its own victims the platform monument was destroyed just hours after its inauguration[19]. And renovated with equal immediacy. Meanwhile the roadblocks erected to control – and block – citizens’ passage through the city and to Tahrir seem to have become permanent installations. The check points wear “revolutionary” skins: The heavy metal gates on Qasr al Nil Street are painted in the colours of the Egyptian flag, and posters with celebratory scenes from Tahrir decorate tanks and serve as backdrops on general El Sisi’s election posters.

Symptomatically, the more the icon of Tahrir is utilized by the official regime discourse the more the Square's actual physical presence, its embeddednes in the urban and political fabric of the city, is compromised. Sadat Station, the underground metro station at Midan Tahrir, has been sealed off since the military effectively regained governmental control: The trains run through a brightly lit but void station without pause. The underground entry points are being covered with meticulously white-washed concrete. To me the feeling of passage beneath Tahrir has become an uneasy one, the place so tactilely rendered inaccessible below its surface. I tried to capture the scenery on camera from inside a moving metro wagon, but was prevented by my fellow travellers in the women’s wagon who thought it better to hand me over to police officers at the next stop. They held me there for a couple of hours critically reviewing the contents of my memory card, which contained nothing but the darkness of the tunnel leading to Tahrir and, by chance, a thirty second freeze-frame of an empty stage, a test shot from the university theatre at the American University’s Downtown campus.

In the winter of 2013 Egyptian artist Lara Baladi wrote:

After January 25, 2011, Tahrir surely replaced the pyramids as the ultimate cliché – a new synecdoche for Egypt. The square continues to be the center of protests, a synonym for political power and the barometer for the revolution’s failure or success. Images of the square have become part of our daily visual consumption routine. At times Tahrir appears to be a parody of itself.[20]

The circuit of endless reproduction that takes place both in the form of physical re-enactments and as an implosion of imprints in the digital sphere, may have initiated a process that eventually leads to Tahrir’s iconic deflation. The intentional over-writings of the imaginary space Tahrir represents and insistent negation of the political and urban space it forms and is realized in, cause Tahrir to mutate into pure iconoclastic gesture. To me, the image of Tahrir today, in the spring of 2014, more than anything represents a void: a void pertaining to Tahrir's integrity as a political symbol and a void that feeds on the absence of democratic political action within its physical premises.

Mikala Hyldig Dal is an artist and curator based in Cairo and Berlin. Between 2011-2013 she was a lecturer at the German University in Cairo and the American University in Cairo. Her artworks have been internationally exhibited and she has worked curatorially on exhibition projects, publications and artist exchange programs in Germany, USA, Iran, Syria and Egypt. In 2013 she published the book CAIRO Images of Transition. Perspectives on Visuality in Egypt 2011-2013 at Transcript-Verlag. Mikala Hyldig Dal is a PhD candidate at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague.

[1] The blank illuminated screens of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s theatres come to my mind; the sum of all projected images produce white monochromes, framed by an absent spectatorship.

[2] In initiatives such as “Tahrir Cinema” image activists screened life broadcasts from Tahrir Square directly on the Square itself and were thus able to observe their own image in real time.

[3] This research is in part compiled in the publication CAIRO Images of Transition. Perspectives on Visuality in Egypt 2011-2013 ed. Mikala Hyldig Dal, Transcript-Verlag 2013

[4] www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosireen

[5] More than eighty people are reported to have lost their eyesight to so-called eye-snipers since January 2011. See for instance: www.theguardian.com/world/shortcuts/2011/dec/18/eyepatches-egpyt

[6] See for instance: Translating Egypt’s Revolution. The Language of Tahrir, ed. Samia Mehrez, AUC University Press 2012 and Cairo Images of Transition. Perspectives on Visuality in Egypt 2011-2013, ed. Mikala Hyldig Dal, Transcript-Verlag 2013

[7] See for instance: http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/egypt-more-500-sentenced-death-grotesque-ruling-2014-03-24, www.buzzfeed.com/sheerafrenkel/egypts-security-forces-once-again-using-virginity-tests-agai, www.nytimes.com/2014/02/24/world/middleeast/concern-grows-over-academic-freedom-in-egypt.html?_r=0 www.en.masrawy.com/News/details/2014/2/5/170090/journalists-worldwide-join-campaign-to-free-journalists-in-egypt, www.stream.aljazeera.com/story/201311062211-0023173

[8] Many tourists of Egypt will have been able to observe this method on the walls of the ancient tombs in Luxor, presumably performed during the Ottoman occupation, as an example.

[9] See for instance: www.policymic.com/articles/83007/the-real-reason-egypt-is-obsessed-with-putting-its-military-leader-on-everything#1073151

[10] The mere taking of a photograph of this symbol can easily be framed as an act of “supporting terrorism”: This was the explanation given to two journalists who were arrested for photographing a man holding a Rabaa poster in September 2013; the man turned out to be partaking in an attempt to entrap the journalists, so William Wells, director of the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo, accounts. The premise of conducting (self-) censorship to maintain the “image of Egypt”, was dominant in the image politics under Mubarak, see for instance Marouan Omara and Johanna Domke Crop in CAIRO Images of Transition. Perspectives on Visuality in Egypt 2011-2013, Mikala Hyldig Dal (red.), Transcript-Verlag 2013

[11] Rabaa Square translates as the forth Square, thus the four fingers. The transliteration was originally produced by minibus drivers as a means to non-verbally communicate Rabaa Square as their point of destination (on further transliterations of Rabaa see also my entry in Walls of Freedom ed. Don Karl & Basma Hamdy 2014)

[12] Compare: An Intellectual History of Cannibalism, Catalin Avramescu 2011

[13] Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins, Jacques Derrida 1993 p1

[14] ICONOCLASH: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion and Art, Bruno Latour 2002

[15] Ikonoklastik und Transzendenz in GegenwartEwigkeit. Spuren des Transzendenten in der Kunst unserer Zeit, Gottfried Böhm 1990

[16] Crises of the Republic Hannah Arendt 1969 p10

[17] “For Arendt, therefore, the polis stands for the space of appearance, for that space “where I appear to others as others appear to me, where men exist not merely like other living or inanimate things, but to make their appearance explicitly.” Such public space of appearance can be always recreated anew wherever individuals gather together politically, that is, “wherever men are together in the manner of speech and action” (H. A., 198–9)... The space of appearance must be continually recreated by action; its existence is secured whenever actors gather together for the purpose of discussing and deliberating about matters of public concern, and it disappears the moment these activities cease.” Hannah Arendt, Maurizio Passerin d'Entreves in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy 2006 / “The distribution of the sensible reveals who can have a share in what is common to the community based on what they do and on the time and space in which this activity is performed… it defines what is visible or not in a common space, endowed with a common language, etc. There is thus an ‘aesthetics’ at the core of politics that has nothing to do with Benjamin’s discussion of the ‘aestheticization of politics’ specific to the ‘age of the masses’… It is a delimitation of spaces and times, of the visible and the invisible, of speech and noise, that simultaneously determines the place and the stakes of politics as a form of experience. Politics revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of spaces and the possibilities of time.” The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, Jacques Rancière 2004 p. 57

[18] As an icon Tahrir seems to function only as a photographic representation; the graphic translations, at least the ones I have seen, do not succeed in transporting the complexity of its circular body

[19] See, for instance: www.theguardian.com/world/2013/nov/18/tahrir-square-memorial-co-opt-egypt-revolution

[20] Lara Baladi When Seeing Is Belonging: The Photography of Tahrir Square, www.creativetimereports.org 2013