December 29, 2015

Re-evaluating (art-) historical ties: The politics of showing Southeast Asian art and culture in Singapore (1963-2013)![]()

Written by Yvonne Low

In[1] 2012, Singapore’s eminent art historian, T.K. Sabapathy, made the following observation:

The institution assumes that lives of artworks in its holdings begin when they enter and take up residence in its premises; the lineage of individual works are not published and appear as largely unknown to SAM. It is as though the histories of works in its collection begin only in and with this museum.[2]

This remark was made during the inauguration of a university gallery, the School of Art, Design and Media (ADM) of Nanyang Technological University (NTU). Not without irony, the critical remark was made against the very institution that he had also helped to open some 15 years ago – the Singapore Art Museum (SAM).

SAM (Fig. 1), which occupied the freshly restored 19th century mission school in 1996 right in the heart of the city-state’s cultural precinct, was one of three museums formed under the aegis of the National Heritage Board (1993) as a result of the White Paper, first initiated in 1989 to convert Singapore into a global city for the arts.[3] SAM was then the proud custodian of the ‘world’s largest public collection of modern and contemporary Southeast Asian art’.

[4] This position is now jointly shared with the recently established National Gallery Singapore (NGS), Singapore’s newest visual arts institution which costs SGD $536 million to reconstruct, and proclaims to oversee the ‘largest public collection of modern art in Singapore and Southeast Asia’.[5]

On both occasions, in 1996 and again in 2012, T.K. Sabapathy was invited to guest curate an exhibition on Southeast Asian art as part of the museum and gallery’s inauguration respectively. In the latter instance, the exhibition, Intersecting Histories: Contemporary turns in Southeast Asian art, at ADM NTU Art Gallery took the opportunity to reflect on and reassess the collection and exhibition history of Southeast Asian art in Singapore. It became a ground-breaking attempt to examine the art historical ties of the region where Sabapathy, together with four other invited authors, discussed the significance and histories of contemporary art from four archipelagic Southeast Asian countries: Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines.[6]

Intersecting Histories makes a cogent case for the comparative study of contemporary art from these four countries in which Sabapathy highlights shared common grounds that have emerged from distinctly unique historical circumstances. In examining the art historical connections of four very prominent works and seminal exhibitions of the respective countries as cases-in-point, Sabapathy demonstrated that the development of contemporary art occurred at about the same time in the respective countries, illuminating similar characteristics and shared concerns.[7] In essence, he has demonstrated the region’s shared history, art-historically. In light of Sabapathy’s contention, Intersecting Histories exposed the perfunctory interest the state has in the histories of art for all the effort that went into amassing a collection on Southeast Asian art and building an infrastructure to house it and display it. Perhaps, Sabapathy’s criticism was not against Singapore’s laudable claims of developing a cultural field, but for not following through.

This was in spite of the country’s declaration at the turn of the millennium to become a Renaissance City, in which the country’s ‘active international’ citizens are to be ‘dynamic, creative, aesthetic, knowledgeable and mature’, and whose ‘arts and cultural scene [will help] to project [their] presence in the global arena’.[8] This “new” Singapore would have distinguished itself from the old state which was seemingly disinterested in art; this time, Singapore will not turn away the offer to buy an ‘invaluable’ collection like the time it did to Singapore’s pioneer artist, Liu Kang, who had twice approached state agencies with separate proposals and been turned away with the same response – that the country had no money.[9]

This was a Singapore who would value the collection of Chinese, Indian and Southeast Asian art belonging to the art museum of then University of Malaya and stored away since 1973 and only assuming a ‘new incarnation’ at the South & Southeast Gallery of NUS Museum in 2002.[10]

How can we then make sense of this ambivalent attitude the nation-state has toward art, and in particular, the arts of Southeast Asia? And what led to this desire to collect and show Southeast Asian art in the last two decades? This paper traces the development of Singapore’s vision to become a global city and its concomitant institutionalization of a ‘Southeast Asian art’ as an initial step to understand how Singapore has positioned herself within the region – both in the past and the present – as the centre of world trade and the emporium of Southeast Asia.

Collecting and Exhibiting ‘Southeast Asian Art’: Beginnings

The Singapore Art Museum was the result of a 1989 White Paper which outlined an arts and cultural policy – deemed the first, since Singapore’s Independence in 1965, that looked seriously into its arts development, an area which the government has by and large neglected.[11] The primary aims were to establish Singapore as a global arts city and to inculcate in the people an appreciation of Singapore’s heritage.

[12] Since then, the newly established National Arts Council, the officiating body controlling the distribution of national funds for resources in all facets of aesthetic production and development in Singapore, has channeled funds to artists and artistic institutions, including scholarships to nurture new practitioners.[13]

When SAM opened in 1996, a major exhibition on modern Southeast Asian art was presented to mark its inauguration. It comprised of two segments, Themes in Southeast Asian Art and A century of art in Singapore. The former was significant because it was the first of its kind – where art of and from the Southeast Asian region was given serious attention and formal contextualization by an institution from within the region.[14] However late in coming, SAM nonetheless became the first facility anywhere in Southeast Asia to collect and exhibit Southeast Asian modern and contemporary art. In fact, no other country in the region but Singapore, it seems, has expended as much effort if not resources in the consecration of a “Southeast Asian art” together with one’s own. This was not to say that the collecting and exhibiting of art of the region began with the inauguration of SAM in 1996, for as seen earlier, collections of Southeast Asian art were traceable to the individual efforts of Michael Sullivan and William Willets, curators of the University Art Museum of the then University of Malaya, Singapore, back in the 1950s.

Nonetheless, Singapore’s more recent claiming of a cultural field – of the Southeast Asian region including its own – is undeniable. Yet, it is interesting to note that such interests or intentions, unlike others, were not explicitly delineated in the White Paper or subsequent policies. In fact, the term “Southeast Asia” appears to be conspicuously absent, with greater focus paid to the global and the international. On this issue, most scholarly work thus far tended to pay attention to how Singapore has turned to the arts and culture as a means to frame a national identity, and how the city-state’s entrenched disciplinary, economics-oriented and instrumental-rationalist approach which characterized much of the policies of the 1970s-80s took a turn towards a more ostensibly socio-cultural development approach from the 1990s onward.[15] The sharp increase in prevalence of state-driven initiatives in the late 1980s and early 1990s was a clear indication of a marked shift in focus to peg Singapore closely to the vision of a global city. For example, the Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA) was formed in 1990 and the National Arts Council the following year, both with aims to develop Singapore into a global city for the arts. This ease at which Singapore was able to position herself within a global art world-industry was similarly observed by political scientist Chua Beng Huat who once remarked:

Singapore has always faced up to and embraced globalization…declaring itself a ‘global city’, making the ‘global’ market an explicit focus of its nascent industrialization and ‘global’ thinking a conscious component of the nation’s ideological framework.[16]

His colleague, Lily Kong, went further to argue that the major motivation behind the cultural policy was largely economic, whilst C.J.W.-L. Wee questioned its effectiveness within the larger framework of cultural identity issues in Singapore.[17] Both have observed the dissonance between rhetoric and reality in light of how strict censorship laws had impeded the creative development and potential desired in an arts hub. One of the questions raised but was left un-resolved was whether Singapore’s geographical location as an island in the near centre of the Malay Archipelago was what caused Singapore to look outwards.

Yet, it seemed evident, as implied in the visions and objectives of a number of cultural institutions discussed here, that underpinning this desire to become a global city is the hope of achieving greater rootedness and specifically greater rootedness within the Southeast Asian region. In the essay The Making of Southeast Asia: Re-imagining a region, Amitav Acharya argued compellingly that Southeast Asia is an artificial notion, in which the nations that constituted it are too diverse politically, socially, and culturally to be considered a ‘natural region’.[18] In accepting his proposition that Southeast Asia is not a natural region, but an imagined and socially constructed community, then the next question to ask is – Why, for example, would Singapore wish to partake in this fictitious conceptualization so earnestly; and more crucially, if such constructions were predicated upon the voluntary and active participation of its constituents, what exactly did Singapore do to ensure the legitimacy of its place in this imagined space?

This is not to say that no other country in the region shared such sentiments. Afterall regional cooperations such as the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) were all very much part of this ‘imagining and creation of brotherly nationhood’, and to the point of ‘fabrication and falsity’.[19] Yet, there is no denying that Singapore’s claiming of the Southeast Asia cultural field, in terms of scale and economic investment, was unprecedented in the region. The actions, as discussed in the following account, are frequently a response to her past entanglements with the region; they are highly revealing as well of how Singapore imagines and positions herself in the region. Here, I will examine the objectives and format of two large-scale art and cultural events, one in 1963 and one in 2013, to address these various questions.

For Singapore’s 4th, Boo Junfeng, a Singaporean video artist, imagines a Singapore that has never separated from Malaysia. His video installation, Happy and Free (2013) (Fig. 2), is a playful take on the Biennale’s theme, If the world changed. Using the format of a music video and in karaoke style, he invites audiences to sing gaily along to the jingle, Happy and Free, initially commissioned in 1963 by Singapore’s Ministry of Culture to celebrate the merger between Singapore, then a Crown Colony, and the Federation of Malaysia. It was a bold piece that took advantage of the theme to play with past memories and to re-imagine new worlds. As Boo revisits this watershed year of 1963 and the tenuous events that eventually culminated in Singapore’s separation and Independence two years later, the Biennale itself was re-visiting the historical and political ties that have given shape and form to the region of Southeast Asia.

Under the organization of SAM, this fourth edition broke tradition by introducing a new format – 27 curators from within the Southeast Asian region were invited to collaborate and deliver their visions. This was a marked departure from earlier formats where a team of mostly foreign curators and art directors were assembled to manage the event, usually no more than three. The aim was also to steer away from the more rigid country pavilion-style such that the works of 82 artists and artist collectives would be presented as a result from engagements across and between the curators representing the respective countries. The tone and tenor of SB 2013 was undoubtedly closely aligned with the institution’s long-standing interest in Singapore and Southeast Asian contemporary art practices.[20] Many of the pieces were commissions, so an event such as this also enabled the institution to strategically build their collection of the region.

In the opening message, the director of SAM, Susie Lingham, wrote:

It is hoped that each visitor to ‘If the world changed’ will experience the deep connectedness within the region, and at the same time, cultivate an appreciation for the sheer cultural and artistic diversity in contemporary Southeast Asia – a diversity alert and alive to all its influences, anxieties and sense of being (my italics).[21]

This hope, of inspiring qualities of ‘connectedness’ and appreciation of ‘diversity’ of the region, is far from new. It goes as far back as to the very first South-East Asia Cultural Festival, held in and hosted by Singapore in 1963.

1963 was a year of great change – not least of all were changes to political affiliations within Southeast Asia as territories underwent extensive reconfiguration. This period marked the imposition of a new order, the Nation, which was itself a modern political entity where older forms of society and communal life were removed and in its place the emergence of the bourgeoisie and the “common man” called forth the need to think of one self as part of a broader national identity and to commit to a common national culture.[22] The urgency of establishing a common identity was similarly vividly felt in the island of Singapore, which sought to bridge the gulf separating her and the Malaya Peninsula on grounds of a common Malayan identity. Singapore was singled out from the Straits Settlements to become a Crown Colony. It was excluded from The Malayan Union scheme and attained self-governing status in 1959.

[23] Singapore’s Independence came with the condition that her re-union with the Malayan ‘hinterland’ would be successful.[24]

The Singapore National Theatre, the country’s first national icon which took four years to build, was planned to open in time for the South-East Asia Cultural Festival. T.K. Sabapathy observed how the festival signaled Singapore’s claim that it was a formative site for ‘showing, representing Southeast Asia (and Asia) as a cultural field’ and for this reason as well, the Singapore National Theatre was seen as ‘symbolizing the emergence of Singapore as an independent (from colonialism) entity’, within a new configuration designation as Malaysia.[25] Originally conceived in 1961 as an international arts event, by the time the event took place in 1963, the festival promoted instead “South-East Asia” as a cultural entity. Ethnically, geographically and historically the countries of South East Asia are either distant relatives or close neighbours. In the past, because of the obstructions created by colonial rule, these countries had no intercourse, at least in the realm of art and culture. Despite their close proximity, the people hardly had any opportunity to enjoy and appreciate one another’s arts and cultures, let alone organize cultural exchange.[26]

As the above foreword makes clear, the festival provided a means for the region’s post-colonial nations to come to terms with the obstructions and to return to a past of congenial cultural exchange it claimed to have purportedly always existed. The political overtones of anti-colonialism were nonetheless clear, as was its collective message against communism where no communist country was invited.

What was less clear however was the nature of this common culture that these nations purportedly shared. Its ambivalence was further complicated when performances from the different countries were expected to call forth familiar echoes that related one to the other and still maintained national distinctiveness. Jennifer Lindsay observed that the festival performances tended to present three, broad thematic images: of indigenousness and classical antiquity; of multiracialism and harmonious coexistence; and of modernity, presented as film stars, fashion and glamour.[27] The second was most clearly portrayed in the “multiracial” performances put up by Malaya and Singapore in part because both sides were campaigning to create a common Malaysian culture in lieu of their impending merger. According to Lindsay, this one occasion of cultural display saw the intersecting of national, regional and global factors. The festival in the midst of the Cold War, she argues, became a diplomatic deployment of the arts, epitomizing the way culture is employed to bolster and justify political communities.

Having inherited a population of largely Chinese migrants and Straits Chinese in a predominantly Malay zone, Singapore was particularly anxious to secure a future envisaged as part of a larger territorial entity. Their exclusion from the Greater Malaya Confederation, otherwise known as Maphilindo, formed in July that year would certainly add to their anxiety.[28] The chairperson of the festival committee explained that the festival set out to re-forge a sense of kinship among nations of the region, one that was disrupted and obscured by colonial rule; by hosting the festival, according to official statements, Singapore could ‘play its part in demonstrating Asian cultural heritage’.[29]

It was therefore no coincidence that the festival was timed to take place in August, just before the official merger.

Singapore’s union with the hinterland was short-lived and the independent Republic of Singapore was created in 1965 amidst tension amongst the various racial groups and the political fractions. As Singapore set about building her own nationalist structures of hope and inventing new values that are desired in Singaporean, not “Malayan” citizens, it was clear that the events of 1963 left an indelible mark. In particular, the potency of “culture” to subserve the political agenda and overcome racial differences in both the nation and the region was not forgotten.

Re-evaluating historical ties: Art, Play and the Spectacle of Hope

According to the 1963 State of Singapore Annual Report, The South-East Asia Cultural Festival was deemed ‘a landmark in the cultural history of the state’ supporting ‘the Government’s social and economic objectives’.[30] Notions of ‘connectedness’ and ‘diversity’ – as articulated most passionately during SB 2013 – were already very much part of the rhetoric back in 1963 and used especially to justify the celebratory overtones of the festival. For example, in the list of objectives originally stipulated for the 1963 Festival, it was clear that the Festival had aimed to position Singapore in the following manner: (a) a centre of world trade and the emporium of South-East Asia; (b) a place for capital investment and industrialization; (c) an attraction for tourists in view of its cosmopolitan character and it being a very convenient stepping-stone for further travel in South-East Asia; and lastly, (d) a meeting place of the four major cultures of the world – Malay, Chinese, Indian and Western.[31]

Terms such as “centre”, “cosmopolitan”, and a place of “attraction” used then to describe Singapore’s role and position in the region were also more recently echoed in recent policies, key among which included the watershed 1989 report on the Advisory Council on Culture and the Arts (ACCA). The White Paper argued that the building of arts facilities would help to ‘attract’ world class performances and exhibitions, and create ‘a more congenial environment for investors and professionals to stay and tourists to visit Singapore’.[32]

Further, in 1996, as described in a statement from the Chief Executive of Singapore Tourist Promotion Board, Tan Chin Nam, the arts were what would bring ‘colour’ to the cosmopolitan city:

By their magic, the arts enrapture visitors from all over the world in countless ways. By their endless variety, they tantalise visitors to come to Singapore again and again […] The time has come for us to invite the world to join in our cultural feast.[33]

More recently in a statement by Lee Suan Hiang, the Chairman of Steering Committee of the 2006 Singapore Biennale, the successful implementation of contemporary art development in Singapore was seen to augment the young nation’s position within the wider global circuit as an international hub:

This inaugural international biennale of contemporary art is a culmination of the growth in visual arts in Singapore, underlining Singapore’s position as an international visual arts hub, as well as a vibrant cosmopolitan city (my italics).[34]

As is clear in these various examples, the rhetoric employed in current policies is cognizant with that used in the past. Whilst the term “South-East Asia” may be conspicuously absent in the latter instances, it is nonetheless communicated visually and spectacularly vis-à-vis the art that was collected and commissioned for display and for appreciation. The grand gestures of celebration to show Singapore as a ‘vibrant cosmopolitan city’ offering to the world a ‘cultural feast’ continues to underscore the tone and delivery of the SB 2013. At the 1963 Festival, there was singing, dancing, and the display of traditional and contemporary art from all the countries involved – it was in many ways a spectacle, to galvanize feelings of connectedness through diversity. At the SB 2013, these feelings were similarly invoked in the commissioning and the presentation of Southeast Asian contemporary art.

Works by Cambodian and Indonesian artists for example would certainly imbue an audacious combination of wonder and instruction, drawing huge crowds of viewers to contemplate, appreciate and learn about the icons, motifs and art of Southeast Asian traditions that have been re-interpreted in contemporary forms. For example, Svay Sareth’s Toy (Churning of the Sea of Milk) (2013) (see Figure 3), a massive sculptural piece spanning a total of 15 metres in length and 5 metres in height, surely towered over the visitors, impressing upon them the sheer magnitude of its size. Constructed not with stone but cloth, this piece reconstructs the famous Mahabharata battle scene of The churning of the sea of milk depicted on the bas-relief of the ancient temple, Angkor Wat. Refashioning the characters into these larger than life, three-dimensional gigantic toy structures, Svay uses the trope of play to mock the illusion of amicable collaboration in political systems.

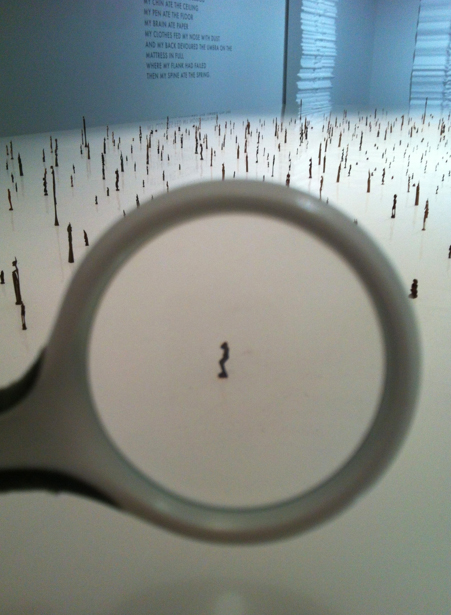

In yet another instance of wondrous reconfiguration are the miniature figurines by Indonesian artist Toni Kanwa (b. 1959). Figure 4 shows indigenous sculptures of the region being shrunk so much that they resembled grains of sand from afar. Cosmology of Life (2013) comprises of 1000 talisman-like sculptures which the artist hand-sculpted. In a bid to draw attention to lost traditions of indigenous cultures of the peoples of Kalimantan, Papua Nias and Sumbawa, Kanwa’s re-presentation of familiar icons into diminutive structures served to further underscore the mysticism of nature and spirituality. In this case, the spectacular is invoked vis-à-vis the exaggeration of scale – here, the only means in which to view the figures was through a viewing aid: the magnifying glass. This act of peering through a viewing device served to not only enhance the clarity of the object but to create a sense of being present; in return, the viewers are rewarded with a sense of awe typified by experiences of child-like fascination that are often associated with such acts of curious exploration.

In both examples, the spectacular has been employed as both a strategy and a trope for which the diverse cultures of Southeast Asian nations could be presented, consumed and enjoyed. Adopting the Biennale format has enabled the nation-state to re-imagine the region in spectacular ways. Notwithstanding the subversive capability of art, on the outset, under global scrutiny, Singapore was able to communicate, in the most perfunctory but clear manner, its place as a centre of world trade and the emporium of South-East Asia in which visitors would be rewarded with a cultural feast; yet, as seen earlier, this was already an objective long stipulated in 1963.

A coda

The White Paper implemented by the Singapore government to convert Singapore into a global arts city echoed many of the concerns and objectives initially raised in 1963, albeit in markedly different political circumstances. In conclusion, this paper has presented a gross overview of some of the motivations, actions and methods in the positioning and imagining of Singapore within the region by the cultural agencies of the nation-state. I have shown that there was a clear precedence to Singapore’s about-turn to arts and culture in the 1990s. Far from new or sudden, the desire to convert Singapore into a global city of the arts was for a long time brewing, and its strategic positioning was examined in light of specific political developments. By examining some of Singapore’s present concerns and past entanglements, I have demonstrated that Singapore’s claiming of a cultural field vis-à-vis the institutionalization of a “Southeast Asian art”, reveals a self-conscious desire to position itself not only as a global city but more precisely, a global city of Southeast Asia.

What was not shown, due to space constraints, and to return to the earlier point on how laudable claims were not followed through adequately, is that Singapore’s approach toward art and culture is disproportionately skewed toward ostentatious display, in part to galvanize a common regional identity in a nationalist direction. Far less attention was paid in the development of an art discourse or in the cultivating of art historians or cultural workers who could make sense of the last forty years of shared history and identify common threads of region-ness in art.[35]

Interestingly, the newly established National Gallery Singapore appears to be treading on similar footsteps as SAM in its avocation of being the leading institution now in the collection and exhibition of modern Southeast Asian art. Officially opened in November 2015, it now boasts of being home to the largest public collection of Singaporean and Southeast Asian art in the region, having culminated 8000 pieces of artworks. The gallery’s director, Eugene Tan, remarked that the public will be surprised to see the ‘depth, the richness and diversity of art that has been produced in the region’; the lack of art appreciation was attributed in part to the lack of a ‘dedicated space to display Southeast Asian art’, till now.[36] Yet, as is clear from the above discussion, the showing of Southeast Asian art and culture has for a period of time been a very significant legacy of the nation’s cultural and economic design.

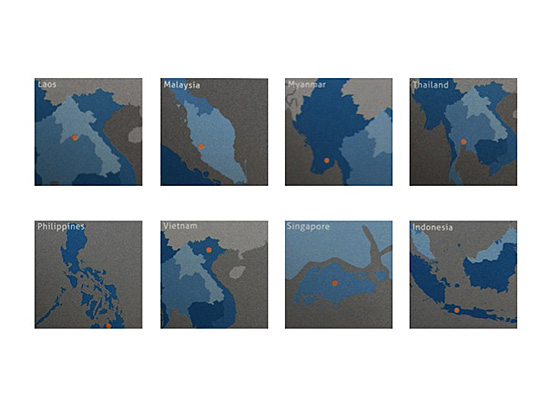

In this attempt to briefly recall and re-evaluate historical ties, I have demonstrated that the showing of Southeast Asian art and culture in Singapore cannot be viewed in separation from the politics of its time. The visual, as seen in its many uses and functions here – to awe and to fascinate, to bring color and vibrancy to a country, has been deployed historically and politically to serve particular agendas: most evidently, to achieve connectedness and rootedness in the region. Indeed, the hope of achieving this was clearly fervently embraced; how else was it possible to explain the subliminal use of ideograms as seen in Figure 5. Found on the top right corner of each page of the SB 2013 catalogue, these ideograms served a very practical purpose: to visually inform the reader the nationality of the artist. But it also harbours a more subtle ideological function. By framing the respective countries within equal-sized boxes, both scale and size have now been given new meanings. Here, in this re-imagining of the region, there is certainly no telling the true size of the country.

Yvonne Low researches and writes on the modern and contemporary arts of Southeast Asia. She was recently awarded the doctoral degree for her thesis on Women artists: Becoming professional in Singapore, Malaya and Indonesia. She presently works as a Project Administrator for the Getty-Funded research project, Ambitious Alignments: New Histories of Southeast Asian Art, operating out of the Power Institute, University of Sydney, and as an academic tutor with the University of Sydney. Her research interests include Asian modernities, cultural politics of art development, feminist art history, women’s history and more generally the colonial histories of British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies and related art historiographical issues of the region. She has contributed essays to the Routledge online encyclopedia, books, peer-reviewed journals such as Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, specialist art magazines and major exhibition catalogues such as the 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (2009) and Intersecting Histories: Contemporary Turns in Southeast Asian Art (2013).

[1] An early version of this paper was first presented at the conference, Southeast Asian Studies Symposium 2014: Southeast Asia in Transition, University of Oxford, 22-23 March 2014.

[2] T.K. Sabapathy, “Introduction” in Intersecting histories: contemporary turns in Southeast Asian art (Singapore: NTU, 2012), p. 28.

[3] The other two included the National Museum of Singapore and the Asian Civilizations Museum.

[4] See for example, Clara Chow, “Art with edge,” The Straits Times, Aug 23, 2005. Note however that this statement is no longer reflected in SAM’s official website, which has since been updated to reflect the latest changes in their mission and vision to focus and specialize in ‘contemporary practices’ of Singapore and Southeast Asia. This is following the changes made institutionally to incorporate SAM as an independent company, and the opening of the National Gallery Singapore which focuses on modern art in Singapore and Southeast Asia.

[5] See their official website, https://www.nationalgallery.sg/about/about-the-gallery [accessed on 6 Dec 2015].

[6] The four invited authors include Yvonne Low, Seng Yu Jin, Aminudin TH Siregar and Adele Tan.

[7] See his essay, “Intersecting Histories: Thoughts on the Contemporary and History in Southeast Asian Art” in Intersecting histories: contemporary turns in Southeast Asian art (Singapore: NTU, 2012), pp. 36-85.

[8] Renaissance city report: Culture and the Arts in Renaissance, (Singapore. Singapore: Ministry of

Information and The Arts [MITA], 2000), 40.

[9] At the Art vs Art conference, Liu Kang, guest-of-honour, recounted in his speech stories of how he had approached the former Ministry of Culture and later the National Museum, once to buy over an invaluable collection that was in his opinion rare and priceless because it included works spanning the Tang, Sung, Yuan, Ming, Qing periods, and second to buy a Xu Beihong painting that had significant value to Singapore’s pre-war history. Both had been rejected. See Art vs Art: Conflict & Convergence (Singapore: The Substation, 1995), 12-14.

[10] See T.K. Sabapathy, “Introduction” in Past, Present, Beyond: Re-nascence of an Art Collection ed. T.K. Sabapathy (Singapore: NUS Museum), 2002, 8-9.

[11] The ACCA report in 1989 mapped out a cultural policy to make Singapore a global city for the arts. Since then, NAC had channeled funds to artists and artistic institutions, including scholarships to nurture new practitioners and several museums of art and Asian civilization were initiated. Subsequently, the Renaissance City Project Report in 2000 documents an approved budget of $50 million to be spent over five years. Singapore’s first pre-tertiary specialized arts school, School of the Arts (SOTA) began operation on 2 Jan 2008. The Cultural Medallion was initiated in 1979 by then acting Minister for Culture with the purpose to acknowledge the exceptional artistic talent and achievement of artists in Singapore and has come to signify as the highest award. For further discussion, see Yvonne Low, “Positioning Singapore’s Contemporary Art”, Journal of Maritime Geopolitics and Culture 2, no. 1 & 2, (2011): 115-137.

[12] See for example, Singapore: global city for the arts (Singapore: Tourist Promotion Board and Ministry of Information and the arts, 1995), unpaginated. On the position of Singapore as a Global City for the Arts, see Kwok Kian Woon and Low Kee Hong, “Cultural Policy and the City-State: Singapore and the ‘New Asian Renaissance’” in Global Cultures: Media, arts, policy and globalization ed. Diana Crane, Nobuko Kawashima, Ken’ichi Kawasaki (London: Routledge, 2002), 149-168; and chapter “Arts in a Global City: 1990s” in Venka Purushothaman, Making Visible the Invisible: Three decades of the Singapore Arts Festival (Singapore: National Arts Council, 2007).

[13] See The power of the arts [corporate brochure], (Singapore: National Arts Council, 2006), 2.

[14] T.K. Sabapathy, ‘Introduction’ in Modernity and Beyond: Themes in Southeast Asian Art, ed. T.K. Sabapathy, Singapore Art Museum, 1996, 7-9. For example, both Japan and Australia were noted for spearheading and driving such initiatives in the Asia-Pacific region beginning first with the Fukuoka Art Museum’s Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale in 1979-80 (initially as an event every 5 years and later in 1999 every 3 years) and the Queensland Art Gallery’s Asia Pacific Triennial (APT) in the 1990s (1993/96/99). In the accompanying catalog, Sabapathy remarked: ‘to date, not a single perspective or framework for the study of modern artists and art of the region has been mooted by writers or scholars from countries in the region. Those from other regions are busily embarked upon the task of mapping Southeast Asian art history, most especially Japan, Australia and the USA’.

[15] Singapore went from turning away the rare opportunity to collect art of historical significance on grounds that the country has no money to spend on art to pledging $500 million in 1995 to build a world class arts centre before the year 2000. For further discussion, see Yvonne Low, “Singapore’s Modern Art: Modern aesthetic responses of Overseas Chinese and Chinese Singaporeans in Singapore”. Unpublished Masters’ Thesis, University of Sydney, 2009.

[16] See Chua Beng Huat, “Liberalization without democratization: Singapore in the next decade” in Southeast Asian Responses to Globalization: Restructuring governance and deepening democracy, eds. Francis Loh Kok Wah and Joakim Ojendal (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005), 57-82.

[17] See for example C.J.W.-L. Wee, 2007; Lily Kong, “Cultural policy in Singapore: negotiating economic and socio-cultural agendas”, Geoforum (For Special Issue on ‘Culture, Economy, Policy), 2000; Ruth Bereson, “Renaissance or Regurgitation? Arts Policy in Singapore 1957-2003”, Asia Pacific Journal of Arts & Cultural Management 1, no. 1, (December 2003): 1-14.

[18] Refer to Amitav Acharya’s essays – ‘The Making of Southeast Asia: Re-imagining a region’ in Singapore Biennale 2013: If the world changed, Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2013, 15-20; and ‘Imagined proximities: The making and unmaking of Southeast Asia as a region’, Southeast Asian Journal of Social Sciences, 27(1), 55-76.

[19] Apinan Poshyananada, ‘The Future: Post-Cold War, Postmodernism, Postmarginalia (Playing with Slippery Lubricants)’, in Tradition and Change: Contemporary art of Asia and the Pacific, ed. Caroline Turner. (Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1993), 9.

[20] See “About the Singapore Art Museum”, https://www.singaporeartmuseum.sg/about/index.html [accessed on 6 Dec, 2015]

[21] Susie Lingham, “Being, in the Midst of Sea-Chang”, in Singapore Biennale 2013: If the world changed, (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2013), pp. 6-7.

[22] A subject that has been extensively studied; see for example Rupert Emerson, 1962, 93. See also Terence Chong, Chapters 2 & 4 in Modernization trends in Southeast Asia (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian studies, 2005). The author presents a succinct discussion on citizenship and ethnicity in the context of nation and national identity.

[23] Leo Suryadinata, Chinese and Nation-building in Southeast Asia (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2005) 35-36. See as well Ronald Provencher (1982, 148-149) for the implications of the scheme in stripping Malay sultans of their sovereignty.

[24] Tunku himself had remarked that the road to merger lay ultimately in all the races of Malay developing a Malayan outlook and loyalty. See Allington Kennard, “The year of merger,” The straits times annual, 1963.

[25] T.K. Sabapathy, 2012, p. 49.

[26] Cited in Jennifer Lindsay, ‘Festival politics: Singapore’s 1963 Southeast Asia Cultural Festival’ in Cultures at war, The cold war and cultural expression in Southeast Asia, ed. Tony Day and Maya H.T. Liem, Southeast Asia Program Publications, Cornell University, 2010, 239. Foreword by Mr. K.C. Lee, chairman of the First South-East Asia Cultural Festival Committee and the National Theatre Trust in Souvenir 1963, 57.

[27] Ibid., 242.

[28] Although short-lived, this association demonstrated the impact of perceived fraternal relations between countries on the basis of race and culture (in this case, Malayness). Yet it was the fear that Malaysia following its merger with Singapore would become a second China that had in turn justified the exclusive concept of Malayness and driven the impetus to form such an ideological network of nations, Maphilindo. See for example, Mohammad Hatta, “One Indonesian view of the Malaysia Issue,” Asian Survey 5, no. 3 (March 1965): 139-143. Hatta uses his personal experience in Malaysia to explain his views about the strong sino ties the Chinese living in Singapore and Malaya still have with China, their ‘original’ homeland.

[29] See Jennifer Lindsay, 2010, pp. 227-246 and T.K. Sabapathy, 2012, pp. 36-85.

[30] Ruth Bereson “Renaissance or regurgitation? Arts policy in Singapore 1957-2003” Asia pacific journal of arts and cultural management vol 1 issue 1 Dec 2003, pp.1-14

[31] Cited in Jennifer Lindsay, 2010, pp. 227-246.

[32] Advisory council on culture and the arts (1989), Report of the advisory council on Culture and the Arts April 1989, Singapore.

[33] Singapore Tourism Promotion Board (STPB), Destination Singapore: The Arts Experience, (Singapore: STPB, 1996).

[34] Lee Suan Hiang, “Chairman’s Welcome”, belief: Singapore Biennale 2006, (Singapore: NAC, 2006).

[35] There remained, for example, to date, no proper art history or museum studies course in the universities of Singapore, which meant that suitably qualified cultural workers are either trained overseas or sourced from overseas.

[36] As quoted in Hilary Whiteman, “National Gallery Singapore finds first home for unseen art”, http://edition.cnn.com/2015/11/25/arts/national-gallery-singapore/ [online] [accessed on 6 Dec 2015]. Tan attributed the lack of a dedicated space for Southeast Asian art as one reason for the state of art appreciation in Singapore. The National Gallery Singapore seemed keen to boost this area and has teamed up with a local university, with a view to create Singapore's first undergraduate degree in art history.