December 28, 2016

Reading conflict on the walls of Buenos Aires, part 2

Written by George Kafka

Commercial conflict

Looking beyond socially orientated conflicts over urban space, this essay will now consider the frictions that exist between commercially orientated urban media and the street artists who attempt to counterbalance the power that advertisements exert on the visual landscape of Buenos Aires. The debates over the place of both advertisements and graffiti in modern society cover remarkably similar ground. Both provoke considerations of public/private ownership of urban space, the aesthetic qualities of the city and citizen identity.

The overlap between these two forms of urban media is particularly evident in two recent examples of Latin American cities’ urban cleanliness policies: ‘cidade limpia’ [clean city] in Sao Paolo and ‘limpiar la ciudad’ [clean the city] in Buenos Aires. The former, introduced in 2007, ‘put into effect a radical, near-complete ban on outdoor advertising.’[19] The policy was introduced by then mayor, Gilberto Kassab, who saw the city overrun with advertisements as part of a wider problem of pollution: ‘Of all the different kinds of pollution, visual pollution is the most obvious.’[20] Following the implementation of the law, a registry has been set up to protect street art by important Brazilian and international artists that was under threat of destruction.[21] In stark contrast, ‘limpiar la ciudad’ is an anti-graffiti campaign put in place by Buenos Aires’ city mayor, Mauricio Macri, in 2010 ‘‘con el objetivo de reparar y limpiar las fachadas afectadas por los graffitis en todas las comunas de la ciudad’[22] The question that arises from these opposing pieces of legislation is who is legitimate to intervene in public spaces? For some scholars and artists, the imposition of advertisements on public space is an affront that should be combatted. British street artist Banksy, for example, posits that ‘the people who truly deface our neighborhoods are the companies that scrawl giant slogans across buildings…they started the fight and the wall is the weapon of choice to hit them back.’[23] Similarly, Naomi Klein argues ‘streets are public places…and since most residents can’t afford to counter corporate messages by purchasing their own ads, they should have the right to talk back.’[24]

![Figure 6: RRAA.-; ‘Y mientras tanto en otro lugar del mundo…alguien pensando en otro lugar del mundo’ [And meanwhile in another part of the world…someone thinking about another part of the world.’] Figure 6: RRAA.-; ‘Y mientras tanto en otro lugar del mundo…alguien pensando en otro lugar del mundo’ [And meanwhile in another part of the world…someone thinking about another part of the world.’]](/images/stories/no17/figure 6.jpg)

Buenos Aires based artist RRAA.- is one such artist who is ‘talking back’, following on in a tradition of artists who vandalise advertisements in order to undermine their commercial message— what he refers to as ‘aesthetic vandalism’. RRAA.-‘s work comes in two forms. Most of his pieces involve pre-existing advertisements, on which he will paint over the faces of the models pictures leaving holes for the eyes and mouth as well as a subtle neckline. In other works RRAA.- will write his own slogans on blank billboards. Slogans include ‘Un beso cuesta solo tres segundos’ [A kiss only takes three seconds] and ‘Y mientras tanto en otro lugar del mundo…alguien pensando en otro lugar del mundo.’ [Meanwhile in another part of the world…someone thinking about an other part of the world] (Fig. 6). These interventions are, for RRAA.-, an attempt ‘to undermine the commercial message of the advertisements and ‘communicate somthing different.’ He argues that the amount of advertisements in public life in Buenos Aires has gone too far[xxv]. Crucially, his use of the very billboards that he opposes allows him to take the size and natural magnetism of traditional advertising to subvert its original message. As is evident in Figure 7, the covering of the face has the effect of actually humanising the figure while distracting the viewer from the brand being promoted.[xxvi] Exposing the eyes allows an insight into the individual behind the exaggerated poses and false expressions that the billboards typically present. By exposing their eyes and mouth, RRAA.- encourages the passer-by to connect with an individual as opposed to a model or a product.

In RRAA.-‘s word-based pieces, the artist takes a similar approach. He appropriates a familiar part of the visual culture of advertising while twisting its orthodox function into something unexpected and personally engaging. The traditional role of advertisements in urban space is to draw the individual’s attention towards a particular product with the aim of convincing them to purchase said product. RRAA.-‘s phrasing instead encourages the passing individual to engage with themselves and the world around them. Traditional advertising seeks to hold our focus on their product, to draw us into a sense of desire and a need to consume. RRAA.- reminds us that ‘Un beso cuesta solo tres segundos’ [A kiss only takes three seconds], encouraging close personal relationships and emotional connection.

The disparity between these approaches is emblematic of the ways in which urban media are used to define the citizens who exist among them. In line with the neoliberalisation of Argentina in the 1990s, public spaces were among many aspects of porteño life that were privatised for the good of the market.[xxvii] Artists such as RRAA.- can be seen as a part of what Cynthia Gabbay refers to as ‘la recuperación del espacio público…en un intento de frenar la deshumanización de la ciudad….’ She continues, ‘‘Los rostros humanos en la calle, sus palabras y su arte, obligan a la vorágine capitalista a retroceder un paso’’[28] By (literally) defacing adverts across the city, RRAA.- draws attention to the ‘hegemonic hold of corporate architecture over urban space’ and contests corporate control over this space engaging porteños as individuals, not consumers.[29]

Of course, advertising agencies are never likely to take a step back, as Gabbay suggests. Instead the industry tends to evolve. Even the landmark ‘cidade limpa’ law in Sao Paolo did not entirely outlaw advertising from the city; the mayor’s ban coincided with a contract with JCDeaux, the world’s leading outdoor advertising company for ad-funded bus shelters.[30] While not faced with the same sort of Sao Paolo-esque restrictions, advertisements in Buenos Aires have evolved to incorporate the walls of the city, alongside traditional billboards, in styles that are largely indistinguishable from street art and graffiti. Brands such as Adidas and Converse use guerrilla marketing techniques, such as murals and stencils, to spread their brand across the urban landscape. In 2011 Converse launched Wall-to-Wall, an ongoing online project showing street artists creating works commissioned by Converse across the world. The videos, which appear on their website and on their YouTube Channel, are filmed in documentary style (as opposed to highly stylised, high production video advertisements) and feature the artists wearing Converse clothing as they paint their works on the city streets. The Converse logo always features in the work but is never the focus of the piece.

In Buenos Aires, as seen in Figure 8, Converse have used a slightly different approach with a simple stencil of their iconic Chuck Taylor sneaker placed alongside other tags, allowing them to blend in with the urban landscape. The stencils are located in the Palermo Hollywood neighbourhood, within a few blocks of their flagship store. The store itself is decorated by renowned local street artist, and former ad-jammer, Cabaio. As Branding Magazine suggests, ‘[Converse] primarily addresses those to whom it is important to be different and original…Supporting the street art scene, which is mostly youth orientated and associated with activism and freedom, Converse strengthens its “rebellious” image among its target group.’[31]

Similarly, the Adidas stencil (Fig. 9), which depicts the personal logo of Lionel Messi, can be seen as a part of a broader theme in Adidas’ marketing which seeks to link the brand to urban culture. Adidas has sponsored events across the globe promoting ‘la originalidad en la calle’, with one such event in Madrid involving skateboarders, BMX bikers and street artists (Fig. 10). In Buenos Aires, an Adidas collaboration with MTV (named MTV Grip) led to the creation of four online films documenting parkour athletes, a group projecting short films onto the city’s buildings, a wandering DJ and a graffiti artist.

![Figure 10: Poster promoting Adidas’ event celebrating ‘originalidad en la calle’ [Originality in the street] Figure 10: Poster promoting Adidas’ event celebrating ‘originalidad en la calle’ [Originality in the street]](/images/stories/no17/figure 10.jpg)

By engaging with street artists in this way, brands are taking on the unique position of both patron and producer of urban media. Their approach is entirely different to the traditional billboard, which is typically acknowledged as the most effective form of direct advertising.[32] In her book on Advertising, Commercial Spaces and the Urban, Anne M. Cronin argues that newer forms of advertising attempt ‘to emphasise indistinctions between advertisements and commodities on one hand, and people moving around the city on the other.’[33] Cronin’s idea can clearly be applied to the marketing techniques of Adidas and Converse in Buenos Aires. In the videos promoting the Wall-to-Wall and MTV Grip projects, the individual artists are the focus, while the brand takes a step back, with the brand logos only appearing explicitly at the end of the clips. The implication here is that Adidas and Converse understand, and are a part of, the young, creative individuals’ lifestyles as they express themselves in the public spaces of the city. The use of stencils on already graffitied walls communicates the same message. Instead of intervening in or obstructing the urban fabric with billboards, these techniques see the brands’ logos sit subtly alongside tags and stencils, their iconography comfortably mirroring the repeated letters and symbols of the artists’ work alongside them.

Of course, these are not the only marketing techniques employed by the aforementioned companies and as much as they do engage with street art and artists, they are much more prevalent as producers of the corporate architecture that controls much of the urban space of the city. However, their choice to use graffiti and street art as marketing techniques is telling, especially when considered alongside the videos that accompany their urban art projects. The street artist in the MTV Grips video explains, ‘me gusta caminar…andar en bicicleta, recorrer…me encanta estar afuera, de hecho en mi casa ni estoy.’[34] Her identity as a street artist is coupled with her enjoyment of freedom, her desire to wander around the city and be inspired by whatever she experiences and then to create freely. Adidas’ presentation of the street artist, and indeed street art, is inherently linked to freedom of personal expression and an urban environment in which to do this. Accompanied by the videos of parkour athletes, the wandering DJ and the publicly projected films, Buenos Aires is represented as a place of communal engagement and creation, in which the street artist performs a vital role.

Furthermore, by adopting the visual language of street art these brands are reducing the visual friction between billboards and individual expression on the walls of the city; the former often being seen as an imposition on a neighbourhood, the latter an organic contribution. By reducing the visual friction, the brands are subsequently attempting to reduce the ideological friction that is inherent between these two forms of communication. The use of a simple stencil alters the message of the brand from an act of direct advertisement of a product to a simple presentation of a logo, in the same vein as stencil works by street artists. While conflicted in their ideologies, it seems that the use of stencils by major brands is a successful resolution of the spatial conflicts that occur between street artists, such as RRAA, and advertisements. As Cronin suggests, ‘advertising can be considered one element that constitutes an urban, visual vernacular.’[35] The adoption of the Palermo Hollywood neighbourhood’s visual language is a rejection of the architecture of corporate dominance and instead a more egalitarian contribution to the urban vernacular of Buenos Aires.

Political Conflict

![Figure 11: La Guemes, Unidos y Organizados [United and Organised] Figure 11: La Guemes, Unidos y Organizados [United and Organised]](/images/stories/no17/figure 11.jpg)

Urban media such as graffiti and murals have long been linked to politics, with a particular focus on political protest and anti-establishment messages. In Buenos Aires, the legacy of political dissent on the walls of the city extends as far back as 1904 when historian and politician José María Ramos Mejía wrote that the writing on the walls of the city ‘‘……encierra sin duda alguna, particular riqeuza de expresiones impenetrables á los que ignoramos esta ciencia popular sui géneris…’[36] In 1933 the revolutionary Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros visited Buenos Aires and noted the enormous human effort of political subversives who took to the wall of the city to denounce the actions of the oppressive military rule of the epoch: ‘los grupos en cuestión recorrían la inmensa ciudad de Buenos Aires, en acción gráfica de protesta…’[37] In the decades that followed the volume of graffiti on the walls of the city followed a pattern that mirrored the cyclical nature of the political system in Argentina, veering between low levels of street expression during authoritarian regimes and high levels of street expression during democratic regimes. As Chaffee explains, ‘One specific goal [of authoritarian regimes] is cleansing the country of “disruptive” street propaganda…for the military sees this media system as subversive, uncensored, and therefore in need of control.’[38] The authoritarian regime of 1976-83 was no exception, yet it was the particular brutality of this era that explains the explosion of communication on the walls of the city following the return to democracy. Slogans denouncing members of the military government were common in the city as well as more artistic pieces in remembrance of the disappeared. Furthermore, as explained by graffitimundo, it was at this moment that large scale and highly colourful murals began to appear around the city in an attempt to bring some positivity to the city and its people, those who had suffered so much at the hands of military rule.[39]

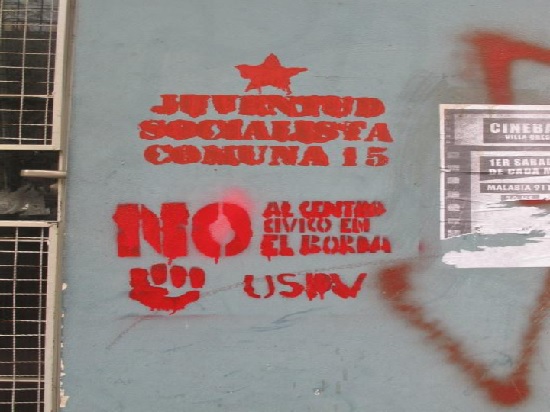

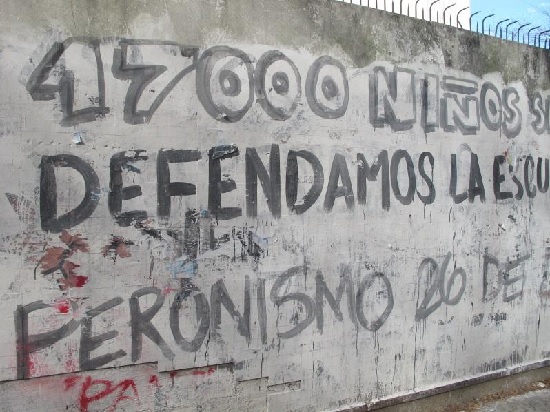

Nowadays the sheer volume of urban media in Buenos Aires reveals a crucial difference in the nature of political conflict on the walls of the city that is not restricted to political protest or dissent. As explained by Lyman Chaffee, the production of street propaganda in the city ‘is no longer only a vehicle for protest. It is considered a fundamental and basic part of the Argentine political system, a means of expressing opinions, announcing political events and persuading others.’[40] As seen in Figures 11-18, numerous political groups use the walls of the city as a fundamental part of their communication. These groups include La Guemes (Fig. 11), El Frente de Izquierda (Fig. 12), Movimiento Popular Patria Grande (Fig. 13) Partido Socialista (Fig. 14), and, perhaps most importantly, La Cámpora (Figs. 15-18). Reading the urban media of these organisations serves as a way of identifying the key political debates that are taking place at a particular time. For example, writing in 1989, Chaffee’s article on Political Graffiti and Wall Painting in Greater Buenos Aires highlights the debate of Argentina’s international debt, the trials of military officers involved in “the dirty war” and accounting for the disappeared among the themes prevalent in political graffiti across the city at that time. Today, one can recognise the low minimum wage, calls for the revocation of Mauricio Macri’s authority as mayor and the lack of school places available for children as pressing issues for the people of the city.

The expression of these ideas on the wall of the city speaks volumes about the relationship between political graffiti and democracy in Buenos Aires. Bringing political debates and ideas into the physical space of the city is symbolic of the highly politicised nature of Argentinian society and the atmosphere of open discussion that exists in the city. As Mitchell asserts ‘While it is no doubt true that the work of citizenship requires a multitude of spaces…at the same time, public spaces are decisive, for it is here the desires and needs of individuals and groups can be seen, and therefore recognized, resisted, or…wiped out.’[41] Sharing conflicts over political ideas in the public space of Buenos Aires is essential in provoking debate and informing the populace of the city.

The use of political graffiti by La Cámpora is of particular interest in this respect. La Cámpora is a political youth organisation that has formed a nationwide body of supporters for the Kirchner administration. The group is led by Máximo Kirchner, the son of the current president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. The blue and white block lettering of La Cámpora’s political slogans is ubiquitous across the nation. In Buenos Aires it is not unusual to find slogans so large that they occupy a whole side of a city block. The group’s politics is characterised by a militant support for the Kirchner administration, with street slogans reflecting whatever the President’s priorities might be at a certain moment. For example, the slogan in Figure 15 reflects an ongoing dispute between the President and major supermarkets such as Coto, whom she accused of robbing from the people of the nation by raising their prices above inflation.[42] Similarly, as aforementioned, recent examples of La Cámpora’s political graffiti has reflected conflicts over the authority of Mauricio Macri and lacking school places (Figs 17, 18 and 19).

The decision to convey these messages through graffiti is significant. La Cámpora’s relationship with mainstream media is notoriously non-existent. Information about the organisation is exclusively communicated through their eponymous publication or through social media networks such as Facebook and Twitter in an effort to counter ‘non-government media and the broadly and vaguely defined “enemies” — those who don’t agree with the president.’[43] These techniques could be read as what Gabbay terms ‘la democracia directa’ [direct democracy], dissolving the dichotomy between the state and the individual through direct communication via social networks and on the streets.[44] Indeed, the language and style of La Cámpora’s graffiti can often be characterised by its lack of direct acknowledgement of its own source. Just as taggers remain anonymous behind their pseudonyms, much of La Cámpora’s slogans are left unsigned, distinguishable only by their familiar colours and font (Fig. 16 is the most emblematic of this). Even the typography of the pieces is very far removed from what one might expect of political communication. The slogans are painted by hand and at times squeezed awkwardly into the wall space that is available. The writers are clearly not artists. However, these attributes create a sense that the slogans are not polished pieces of propaganda but sentiments that come from the people; they have an air of honesty about them.

![Figure 16: La Cámpora, ‘Sí Quiero la Revocatoria en la Ciudad’ [Yes I want the revocation in the city], calling for the removal of Mauricio Macri. Figure 16: La Cámpora, ‘Sí Quiero la Revocatoria en la Ciudad’ [Yes I want the revocation in the city], calling for the removal of Mauricio Macri.](/images/stories/no17/figure 16.jpg)

Of course, as with any political propaganda, La Cámpora’s slogans must be considered with caution. Their ostensibly populist messages are easily exposed as attempts to drum up support for Kirchner’s own political paranoia. The call for the revocation of Mayor Mauricio Macri’s authority is simply an attempt to damage the reputation of the Kirchner administration’s main opponent going into the 2015 general election. Similarly, the scapegoating of supermarkets for rising prices is a mere attempt to mask the administration’s own economic incompetence. However, this does not negate the great symbolic significance of using graffiti as a method of political communication. There can be no doubt that the expression of political conflicts on the walls of the city is to bring them directly to the public. Whether or not the public accepts them is a different matter. What’s important here is the recognition of the walls’ powerful place in the political consciousness of the people of Buenos Aires. By adopting the visual language of graffiti, La Cámpora’s messages refer back to the legacy of political dissent that strongly defines the history of graffiti in the city and is typically associated with democratic struggle. By bringing the Kirchner administration’s political squabbles onto the streets of the city La Cámpora’s graffiti takes on the identity of the individual fighting against “the establishment” (the mainstream media, large corporations), conveniently masking the fact that they are themselves a part of the ruling elite.

![Figure 17-18: La Cámpora, ’17,000 Niños Sin Vacante, Defendamos la Escuela Pública’ [17,000 children without a school place, we defend public schools] Figure 17-18: La Cámpora, ’17,000 Niños Sin Vacante, Defendamos la Escuela Pública’ [17,000 children without a school place, we defend public schools]](/images/stories/no17/figure 18.jpg)

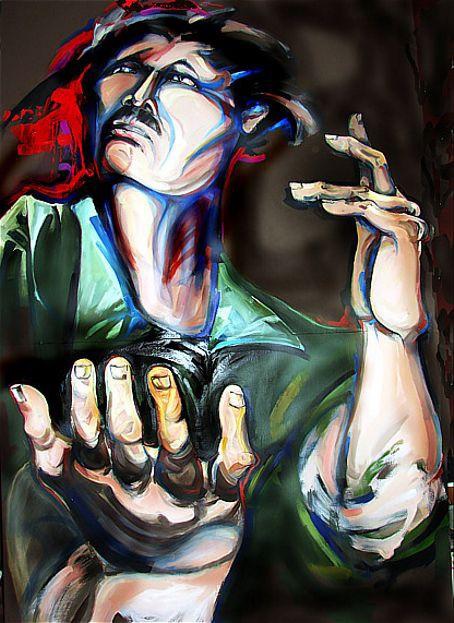

While La Cámpora’s slogans attempt to manufacture popular opinion and community engagement, there are significant works, typically murals as opposed to slogans, that reflect genuine democratic organisation in a community level. Murals in Chacarita (Fig.19), Almagro (Fig. 20) and Caballito (Fig. 21) commemorate the organisation of the ‘Asambleas Populares’ [Popular Assemblies] that sprung up across the city during the social, political and economic collapse in the final months of 2001 (there were around 250 in the federal capital and wider metropolitan region at the movement’s peak). These assemblies were borne out of spontaneous meetings of residents who congregated in the public plazas, parks and street corners, providing a forum for citizens to express their outrage at the events unfolding in the Casa Rosada. One resident of Almagro at that time describes the movement as ‘una defensa a lo que todos vivimos como un ataque.’[45] Neighbours who had previously never spoken became united in shared frustration and desperation in political communities that ‘fulfilled the collective and instinctive need for a forum for direct participation and involvement.’[46] As noted by Valeria Gonzalez, these assemblies fill the void that had been left by neoliberal faliures— ‘entre las ruinas de un modelo económico agotado, la gente construía su ciudad propia’[47]

Although the need for this level of community action has faded, the legacy of these organisations is preserved in dynamic and emotive murals. The piece that stands in memory of the Asamblea Popular Chacarita-Colegiales (Fig. 19) is of particular significance. The mural sits on a small plaza on the corner of Avenida Córdoba and Avenida Federico Lacroze, a typical site for the meeting of the Asambleas Populares. It shows a woman of Amerindian roots, passionately participating in the ‘cacerolazo’ demonstrations of 2001. Her face is at once a vision of fury and despair. On the wall beside her are the names of the victims of police brutality who dies on the 19th and 20th December 2001. The mural stands as a powerful memorial not only to those who died, but also to the action that released the tension of political conflict and personal turmoil onto the streets of the city and into the form of community-led democracy.

Interestingly, the mural itself has a story of conflict beyond the struggles that it depicts. Following its inauguration in 2002 the mural lay untouched, respected by the residents of the neighbourhood, until 2007 when the piece was covered up ‘por el gobierno de Telerman.’[48] Undeterred, the Asamblea Popular Chacarita-Colegiales returned to repaint the mural, this time accompanied with a message spray painted beside the names of the deceased: ‘La Memoria No Se Tapa’ [Memory cannot be covered up].

This is perhaps the archetypal example of the conflicts that occur in relation to the urban media of Buenos Aires and the effects that such conflict can have on the definition of citizenship and the strength of democracy. To attempt to paint over the Chacarita-Colegiales mural was to attempt to erase the legacy of community based organisation that allowed citizens’ voices to be heard in the public domain. After the nation’s political and economic infrastructure was collapsing around them, the people of the city gathered in the only remaining places where they could have some control over the outcome of their lives, the public spaces of their city. The significance of this period is visible in the act of further creating the city that they wished to inhabit: by erecting the mural. The mural represents the voice of the people and their assertion of the right to democracy as well as the right to the city.

Crucially, the voice of the people of the city was not silenced. When their leaders failed them, Argentinians took to the streets to show their anger and resilience; when the mural was covered up it was soon repainted. The mural remains there today, free of graffiti and interference from other urban media. Yet around it is a myriad of city blocks whose faces change daily, even hourly, with accidental scratches, strategic marketing stencils, the latest large scale piece from Cabaio and everything in between. It is in these markings that we can read the clashes between social groups, commercial claims to public space and conflicts that define the very democracy on which Argentina is based. To return to Cronin, ‘Public space functions as a zone in which conflicting interests are played out. But they also show that what counts as such space…is a matter of contention and this involves the core rights of participation in society.’[xlix] This essay has demonstrated that as a crucial part of the public space of Buenos Aires, the urban media that appear on the walls of the city are integral in gaining an understanding of the conflicts that define life in the city. Whether these conflicts manifest themselves through struggles for space between social groups, a splash of paint in protest against corporate interests or the projection of political squabbling into the lives of the people, the walls are essential to the collective creation of both the built environment and the society that moves within it.

George Kafka is a freelance writer and founding member of &beyond

[19] David Evan Harris, ‘Sao Paulo: A City Without Ads’, Adbusters, August 3rd 2007. Accessed at https://www.adbusters.org/magazine/73/Sao_Paulo_A_City_Without_Ads.html.

[20]A. Downie, ‘Sao Paulo Sells Itself’, Time International (South Pacific Edition), Vol. 47, p. 54.

[21]Paulo Winterstein, ‘Scrub Sao Paulo’s Graffiti? Not So Fast, London’s Tate Says’, Bloomberg, August 24th 2008. Accessed at http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=ar4OrAXUisPQ&refer=latin_america

[22] ‘with the objective of reparing and cleaning the facades of buildings affected by graffiti in all sections of the city’ Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires- Jefatura de Ministros, La Subsecretaríá de Atención Ciudadana, February 4th 2011. Accessed at http://www.escritosenlacalle.com/blog.php?page=2&Blog=26.

[23] Banksy, Wall and Piece, (London, 2006), p. 8.

[24] Naomi Klein, No Logo, (London, 2001) cited from Kurt Iveson, ‘Branded cities: outoor advertising, urban governance, and the outdoor media landscape’, Antipode, Vol. 44 (Jan, 20120), p.169.

[25] RRAA.- (15th March 2014), personal interview.

[26] RRAA.-: ‘They remember the exact street corner it was on, they remember the colour I used, but they can’t remember the brand that I painted over. That for me is mission accomplished.’

[27] Verónica Daian, ‘La gestión del espacio público en la ciudad de Buenos Aires’, VI Jornadas de Jóvenes Investigadores, (2011). P.3. Accessed at http://www.aacademica.com/000-093/219.pdf.

[28] ‘the recuperation of public space…in an attempt to slow down the de-humanisation of the city ‘The human faces in the street, their words and their art, force the capitalist maelstrom to take a step back.'’.Gabay, ‘El fenómeno posgraffiti en Buenos Aires’.

[29] Guillaume Marche, ‘Local democracy and public spaces in contest; Graffiti in San Francisco’ in (eds.) Emmanuelle Avril, Johann N. Neem, Democracy, Participation and Contestation: Civil Society, Governance and the Future of Liberal Democracy, (New York, 2015), p.246-8.

[30] Iveson, ‘Branded cities’, p.160.

[31] Jovana Radovanovic, ‘Converse Turns Street Art Into Advertisements’, Branding Magazine, February 20th 2013. Accessed at www.brandingmagazine.com/2013/02/20/converse-wall-to-wall/.

[32] Anne M. Cronin, Advertising, Commercial Spaces and the Urban, (London, 2010), p.23.

[33] Ibid. p.84.

[34] ‘I like to walk…ride my bike, wander…I love to be outside, in fact I’m hardly ever in my house ’mtvgrip’s channel, ‘MTV GRIP – Adidas: Graffiti’, video, YouTube, February 10th 2012; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x8djvNTqelQ.

[35] Cronin, Advertising, Commercial Spaces and the Urban, p. 190.

[36] ‘contain a particular richness of expressions that are impenetrable to those of us that ignore this unique popular science…’ Emilio R. Petersen, ‘El Graffiti en Buenos Aires’, El Portal de Mexico. Accesed at http://www.elportaldemexico.com/arte/artesplasticas/graffiti.htm

[37] ‘…the groups in question travel across the vast city of Buenos Aires, in an act of graphic protest…’, Secretaria de Educación Pública, México, ‘Introducción y selección de textos de Rafael Carrillo Azpeitia’, Siqueiros, in Ibid.

[38] Lyman G. Chaffee, ‘Political Graffiti and Wall Painting in Greater Buenos Aires: An Alternative Communication System’, Studies in Latin American Popular Culture, Vol. 8 (1989), p. 39.

[39] Graffitimundo, tour, April 25 2014.

[40] Ibid.p. 60.

[41] Mitchell, The Right to the City, cited from Boykoff and Sand, Landscapes of Dissent p.7.

[42] Florencia Donovan, ‘Multan a supermercados por faltantes de artículos con precious acordados’, La Nacion, February 15th 2014. Accessed at http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1664362-multan-a-supermercados-por-faltantes-de-articulos-con-precios-acordados

[43] Douglas Farah, ‘La Cámpora in Argentina: The Rise of New Vanguard Generation and the Road to Ruin’, International Assessment and Strategy Center, p.3. Accessed at http://www.strategycenter.net/docLib/20130513_LaC%C3%A1mporaFINAL.pdf

[44]Gabbay, ‘El Fenómeno posgrafiti en Buenos Aires’.

[45] Marina Dragonetti, ‘Arqueología de las asambleas populares’, plazademayo.com, December 20th 2011. Accessed at http://www.plazademayo.com/2011/12/arqueologia-de-las-asambleas-populares/.

[46] Marcela López Levy, We Are Millions: Neo-liberalism and new forms of political action in Argentina, (London, 2004),p.106.

[47] ‘among the ruins of the broken economic model, the people constructed their own city’.Valeria González, ‘Un comentario acerca del documental’, Colegiales, Asamblea Popular, July 17th 2008. Accessed at http://colegialesasambleapopular.blogspot.co.uk/.

[48] Jorge Telerman, the then head of the government of Buenos Aires.

[49] Cronin, ‘Advertising, Commercial Spaces and the Urban’, p. 164.

Bibliography

Armstrong, Justin, ‘The Contested Gallery: Street Art, Ethnography and the Search for Urban Understandings’, AmeriQuests, Vol. 2 (2005) pp. 1-18.

Banksy, Wall and Piece, (London, 2006).

Botnick, Ken and Raja, Ira, ‘The unruly city: Signs, streets, and democratic spaces’ Thesis Eleven, Vol. 113, (2012) pp.94-111.

Bowen, Tracey, ‘Graffiti and Spatializing Practice and Performance’, rhizomes, Issue 25 (2013). Accessed at http://www.rhizomes.net/issue25/bowen/.

Chaffee, Lyman G., ‘Political Graffiti and Wall Painting in Greater Buenos Aires: An Alternative Communication System’, Studies in Latin American Popular Culture, Vol. 8 (1989) pp.37-60.

Daian, Verónica, ‘La gestión del espacio público en la ciudad de Buenos Aires’, VI Jornadas de Jóvenes Investigadores, (2011) pp.1-13. Accessed at http://www.aacademica.com/000-093/219.pdf.

Donovan, Florencia, ‘Multan a supermercados por faltantes de artículos con precious acordados’, La Nacion, February 15th 2014. Accessed at http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1664362-multan-a-supermercados-por-faltantes-de-articulos-con-precios-acordados.

Downie, A., ‘Sao Paulo Sells Itself’, Time International (South Pacific Edition), Vol. 47.

Dragonetti, Marina ‘Arqueología de las asambleas populares’, plazademayo.com, December 20th 2011. Accessed at http://www.plazademayo.com/2011/12/arqueologia-de-las-asambleas-populares/.

Drexler, Jane M. and Hames-Garcia, Michael, ‘Disruption and Democracy:Challenges to Consensus and Communication’, The Good Society, Vol. 13 (2004) pp.56-60.

Farah, Douglas ‘La Cámpora in Argentina: The Rise of New Vanguard Generation and the Road to Ruin’, International Assessment and Strategy Center, pp.1-23. Accessed at http://www.strategycenter.net/docLib/20130513_LaC%C3%A1mporaFINAL.pdf.

Freeman, Richard ‘The City as Mise-En-Scene: A Visual Explration of the Culture of Politics in Buenos Aires’, Visual Anthropology Review, Vol. 17, (Ja, 2008) pp.36-59.

Gabbay, Cynthia ‘El fenómeno posgrafiti en Buenos Aires’, Aisthesis No.54, Dec. 2013. Accessed at http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-71812013000200007.

Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires- Jefatura de Ministros, La Subsecretaríá de Atención Ciudadana, February 4th 2011. Accessed at http://www.escritosenlacalle.com/blog.php?page=2&Blog=26.

González, Valeria ‘Un comentario acerca del documental’, Colegiales, Asamblea Popular, July 17th 2008. Accessed at http://colegialesasambleapopular.blogspot.co.uk/.

Giulianotti, R., and Armstrong, G., ‘’Avenues of contestation: football hooligans running and ruling urban spaces’, Social Anthropology, Vol. 10 (2002) pp.211-238.

Harris, David Evan, ‘Sao Paulo: A City Without Ads’, Adbusters, August 3rd 2007. Accessed at https://www.adbusters.org/magazine/73/Sao_Paulo_A_City_Without_Ads.html.

Harvey, David, ‘The Right to the City’, New Left Review 53, (September-October 2008).

Janches, Flavio ‘Significance of Public Space in the Fragmented City: Designing Strategies for Urban Opportunities in Informal Settlements of Buenos Aires City’, United Nations University: World Institute for Development Economics Research, Working Paper No. 2011/13 (March 2011) pp. 1-12. Accessed at http://www.rrojasdatabank.info/wp2011-013.pdf.

Klein, Naomi, No Logo, (London, 2001) cited from Iveson, Kurt, ‘Branded cities: outoor advertising, urban governance, and the outdoor media landscape’, Antipode, Vol. 44 (Jan, 2012) pp.151-174.

Lefebvre, Henri, The Production of Space, (Oxford, 1991).

Levy, Marcela López We Are Millions: Neo-liberalism and new forms of political action in Argentina, (London, 2004).

Lewisohn, Cedar Street Art, (London, 2008).

Ley, David and Cybriwsky, Roman, ‘Urban Graffiti as Territorial Markers’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 64 (December 1974) pp.491-505.

Marche, Guillaume, ‘Local democracy and public spaces in contest; Graffiti in San Francisco’ in (eds.) Avril, Emmanuelle and Neem, Johann N. , Democracy, Participation and Contestation: Civil Society, Governance and the Future of Liberal Democracy, (New York, 2015) pp.236-253.

Mitchell, Don, The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space (New York, 2003) cited from Boykoff, Jules and Sand, Kaia, Landscapes of Dissent: Guerilla Poetry and Public Space, (Long Beach, 2008).

MTV GRIP – Adidas: Graffiti’, video, YouTube, February 10th 2012; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x8djvNTqelQ.

The Observer, ’50 sporting things you must do before you die’, Observer Sport Monthly, April 4th 2004.

Petersen, Emilio R., ‘El Graffiti en Buenos Aires’, El Portal de Mexico. Accesed at http://www.elportaldemexico.com/arte/artesplasticas/graffiti.htm

Radovanovic, Jovana ‘Converse Turns Street Art Into Advertisements’, Branding Magazine, February 20th 2013. Accessed at www.brandingmagazine.com/2013/02/20/converse-wall-to-wall/.

Robinson, Andrew, ‘Jean Baudrillard: Strategies of Subversion’, Ceasefire Magazine, September 7th 2012. Accessed at http://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/in-theory-baudrillard-11/.

Visconti, Luca M., John F. Sherry Jr., Stefania Borghini, Laurel Anderson, ‘Street Art, Sweet Art? Reclaiming the “Public” in Public Place’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 37, (October 2010) pp. 511-529.

Winterstein, Paulo, ‘Scrub Sao Paulo’s Graffiti? Not So Fast, London’s Tate Says’, Bloomberg, August 24th 2008. Accessed at http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=ar4OrAXUisPQ&refer=latin_america

Young, Alison, Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination, (Abingdon, 2014);

Zukin, Sharon, The Cultures of Cities, (Oxford, 1995). Cited from Cronin, Anne M., Advertising, Commercial Spaces and the Urban, (London, 2010)