September 30th, 2012

The Imprisoned Images

It seems that some events and historical moments cyclically and corrosively become redundant in a limbo of distrust and indifference, caught up by the ideological concepts that served them, unable to free themselves from an aura of spectral truth, and unable to trigger mechanisms of political subjectivation.

This is the case of political prisoners during the military dictatorship and the Estado Novo and of all the contours of the torture to which thousands of Portuguese citizens were subjected over a period of forty-eight years, until 25 April 1974 and the establishment of democracy.

Academic studies dedicated to the subject keep dividing opinions and have apparently not yet been able to uncover, in a cutting and effective manner, the human experience and the testimonial and subjective character of the entire history of political torture in Portugal.

Democracy has been fighting against some degree of official and political resistance to this aspect of national history, perhaps out of a form of categorical tolerance and the appeased character of the Portuguese people, thereby placing amnesia on an ethical level that serves discourses of power and the elimination of themes that might fracture society.

In this sense, every action that tends to overcome this historical and political failure constitutes a fundamental contribution to activating the collective memory and analytically documenting that which has all too often been treated in an abstract and generalized way.

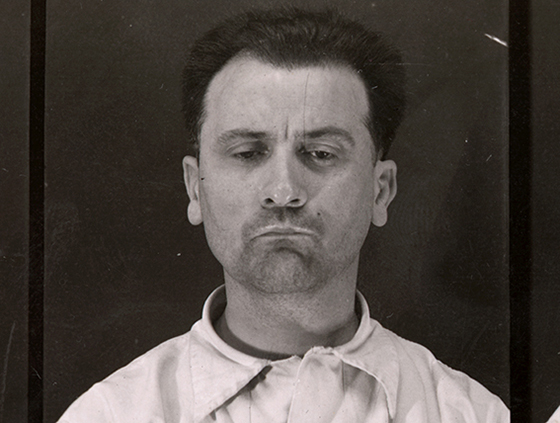

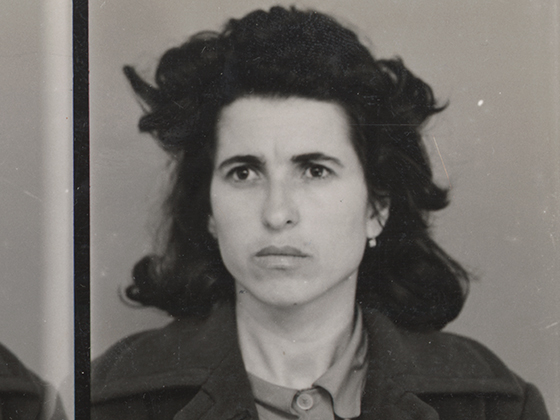

This is precisely the case of Susana de Sousa Dias’s international award-winning [1] documentary 48 [2], which, through an orchestration of archive images and oral testimony, uncovers the violence and brutality exercised by the Political Police (PIDE) over men and women during the forty-eight years of the Portuguese Dictatorship (1926-1974), thus creating, more than a movie, an act of rescue centred on history and the image.

In this paper, we reflect on the image of identity as a model of resistance to abstract concepts of the collective and as a way of counteracting phenomena arising from the historical erasure of memories of repression and torture. It is also our concern to expound on artistic ability as a means of uncovering the invisible dimension of archive images, thus counteracting the use of this ability in political acts intended to normalize its interpretative pulse.

The artist filmed the police photographs of some political prisoners compiled in dozens of albums preserved in a national archive and in each case convoked memories of their personal histories of prison and torture. As the filmmaker herself says, her method for organizing the film was based ‘on a series of sequences, each bearing a specific silence. These silences create not only the cinematographic space of the film but also make us feel the bodily presence of each of the ex-prisoners’.

This ‘bodily presence’ comes to situate the archive images on a perceptive balance with the spoken word, thus weaving an understanding and a deep knowledge of the facts that allows the complexity of their meaning to be grasped. The entire film is construed on the basis of confronting political prisoners with their respective police images, triggering their memories, which then go on to narrate, off camera, their experiences of prison and torture as well as their states of mind at the moment when their photos were taken by the police.

The film captures some of the fundamental aspects of contemporary reflections on the image, as expressed in three main topics:

1. Ethics and the political dimension of so-called historical images.

2. The artistic reading of power images as a tool of counter-power.

3. The uncovering of the meanings of archive images against their abstract interpretation and its disappearance strategies.

With regard to the first topic, let us take a look at the analytical context of 48. Portugal is still a country in which the mechanisms that govern historical knowledge of the dictatorship are frequently framed in a time that is far too remote, involving no stains or possible repercussions on the democratic society that succeeded it.

The work of Susana de Sousa Dias enacts a vindication of the individual and his freedom in a political and social panorama dominated by a lack of analytical and critical sense of the actions of the dictatorship, thereby exposing the whole dimension of violence in the passage between word and image. By the same token, political control and the fading of identity through the photographic image are denounced through the historical and artistic possibility of transforming a visual discourse on repression into an affirmation of the principles of freedom and human rights.

Within the framework of representations and/or testimonies of violence, the image has been the subject of the most wide-ranging analyses and polemics. Its realistic nature has granted it a privileged platform as a witness whose exacerbation has attracted both defenders and detractors, thus making its urgency and validity the focus of a permanent critical and contextual exercise.

Thus, the historical path taken by the image now prevents it from being used and seen as a model of moral reliability, a fact that immediately undermines any ideological discourse on the image. As an instance of this, let us note that the archive in which these images are kept is currently subject to legislation that prevents the public from freely accessing it and knowing the identities of each of the thousands of faces in the photographic albums compiled by the political police.

The prerogative of the ‘right to the image’ and the defence of privacy is the legal concept that serves to control the identity of these images; however, it causes the effects of anonymity and historical ignorance to prevail over victims of repression under the guise of providing a safeguard for civil rights constructed by democracy.

Besides rescuing from anonymity some of the prisoners represented in these archive images, the film undertook the task of rebuilding each of their profiles as a civilian and a citizen. As the filmmaker herself says: ‘I worked with each political ex-prisoner in his or her human condition, and not as a victim. There is a permanent connection between the ex-prisoners’ personal and private lives and the political context’. By establishing this correspondence between the political and the personal dimensions, the film endows the historical images with an ethical dimension that was repressed by dictatorial power and that democracy seems to deny.

These images and testimonies therefore represent a mutual commitment to shift from the immutability and silence inherent in all archive images to a voice that explains and opens up the facts to the public, thereby constituting an exercise in freedom and knowledge whose legitimacy, in a collective framework of democratic amnesia, still seems to be vitally important.

Susana de Sousa Dias has given an identity to these identification photographs. She has made these serial and repetitive flat images of faces, seen from the front and the side, into a statement about the need to strip these archive images not only of their exotic and spectacular dimension but also of their ability to exercise authority and to control knowledge, situating them in a place of critical libertarian awareness.

Archive materials and the archive concept itself have been enthusiastically embraced by post-modern artists, although this has not always resulted in the exercising of freedom over the origin of these materials/ concepts. I believe that the social, political, and civic implications that envelop everything related to the constitution of visual (and not only visual) memories should be the subject of permanent critical refinement, avoiding moralistic polarities, expressing a libertarian interpretation that counteracts their hermeneutical nature.

The anonymity in which the archival function has kept most of these faces constitutes what I call a phenomenon of acquiescing to the ambiguity that exists between truth and interpretation. In the circularity of photographic representation, none of these images, none of these faces, can in themselves throw any light on the lives of the subjects as political captives, besides being an abstract record of identification, crucial to the persecution of and fight against clandestinity. The true relationship of these images with what they represent was designed under an ideological programme that aimed to control the freedom of the people concerned; this being the case, none of these thousands of faces can express, whether individually or collectively, a contextual relationship with what brought them in front of the camera.

In her strategy for understanding and uncovering the horror and torture that took place during the dictatorship in Portugal, the filmmaker chooses ‘to put the image and the word on the same plane’, thereby undertaking what Jacques Rancière considers to be a fundamental strategy of critical reformulation that avoids simplistic oppositions between image and word when horror is being represented. The main challenge will then be ‘the status of the bodies placed in images, and words’, a challenge to which the film responds by giving human density to each of the voices and images, bringing them closer to each of us and thereby helping to construct an active collective memory of political torture during the fascist era in Portugal.

It is the filmmaker herself that raises the film’s main question and concept: ‘What do these images show us and hide from us?’ This question takes us back to the second statement in our analysis of artistic work on images of power as a means of establishing a counter-power consciousness and dialectical historical knowledge.

Some of the prisoners' testimonies reveal that the countenance with which they faced the camera was their last place of resistance against their oppressor. The photograph, which was forcibly taken by the political police, became another weapon of opposition against the regime in the sense that the subjects’ intimate ability to choose the expression with which they faced the camera was one more affirmation, albeit a very subtle one, of that individual freedom for which they were collectively fighting. It is on this premise that the entire film is built, ‘in a way that takes us beyond the surface of things (of images, of words) in an attempt to reveal their intrinsic complexity’ (Susana de Sousa Dias).

The images of these faces, which retain their basic function as stereotypes due to their documental and archival status, are finally transformed by artistic interpretation into people with histories of political resistance, consecrating themselves through this public act of describing and looking at the epilogue of a lengthy period of activity intended to win freedom. Moreover, their history has a common value, a voice that is the mirroring of many other voices that were silenced. Consequently, the filmmaker has decided not to reveal the identity of each of the voices and faces in the film until the final credits, refusing any alignment with the stereotyped and widespread strategies of identification used by the regime that produced the images, instead weaving a counter-power discourse on solidarity with the exercising of the residue of freedom contained in each of these faces.

In the archival silence and legalistic web that envelops them, these images form part of silencing strategies, accessible only to an elitist historical and/or theoretical knowledge that avoids contact with any desire for public disclosure. This is still a discourse of power and repression over the image that may ultimately make the image ‘irretrievable’.

And this is the third point that we wish to highlight.

Walter Benjamin stated that ‘every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably’. The archive image contains within itself that inherent state of non-recognition, that dilution in the form of a document/testimony with abstract outlines, that directing of interpretations under a generalist hallmark. Political persecution and torture during the Portuguese dictatorship has been discussed in a mitigated way by official history, being sustained precisely by the impossibility of recognizing the condition of the political prisoner and affirming his or her testimony.

In this sense, the documentary is built on a methodology whose aim was to highlight that recognition. The montage of images and words aimed to ‘create a space of thought for the spectator’ (Susana de Sousa Dias) that would lie beyond any easy emotional appeal. A relationship between the work and the spectator is thereby established in which it is possible to carry out the task of acknowledging the facts and their complexity, raising doubts and questions and weaving the means by which to resist the superficial and generalist reading of history.

Last but not least, the film also weaves a reflection on the capacity to reinvent new mechanisms of resistance within power scenarios and discourses, on how the most repressed and controlled images can be eroded by the subject’s resilience, in his solidarity and humanism. And also a reflection on how art, rather than being a setting in which victims are exhibited, should summon the spectator to the task of recognizing all potentially irretrievable images.

Translation from the Portuguese version: Paulo Lima Santos, revised by Sean Linney

Emília Tavares is an art historian and curator in the area of photography and new media at the Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea - Museu do Chiado, Lisboa

[1] International Festival Punto de Vista, Navarra, Spain, 2011; FIPRESCI Award, Dok Leipzig, Germany, 2010; Grand Prix Festival Cinema du Réel, France, 2010; Opus Bonum Award, Jihlava Festival, Ckeck Republic, 2010.

[2] Digital Betacam, 93 minutes, 2009. Script, Director and Editing: Susana de Sousa Dias; Film: Octávio Espírito Santo; Sound: Armanda Carvalho; Additional sound: Paulo Cerveira e Valente Dimande; Sound design: António de Sousa Dias; Mixing: Tiago Matos; Post-production director: Helena Alves; Executive Producer: Elsa Sertório; Producer: Ansgar Schaefer; Support: ICA e RTP