July 1, 2011

Blind encounters in the fault lines of an empire

By Paal Andreas Bøe

Blind Dates: New Encounters from the Edges of a Former Empire is the title of an ongoing collaborative project literally based on blind-dating artists, architects and researchers with each other, all of whom have a background from societies that were violently estranged during the rise of nationalism in the territories of the tumbling Ottoman Empire. Too easily such forms of estrangement and hostility have been accepted as facts of history, while less attention has been paid to the status of these historical master narratives as abiding sources of estrangement and conflict today, and the possibility of overcoming them. The Blind Dates Project investigates how such narratives could possibly be revised to facilitate the overcoming of loss, and the rebuilding of destroyed community bonds. The process is based on experimental, imaginative and future-oriented ways of rethinking the past in the present – at times in terms of geography and archeological remains; other times by challenging inherited cultural stereotypes of identity and otherness.

Contracts in blindness

The project title's evocation of the concept of blindness invites a problematization of the very material of the project itself, and with it, the idea of a necessary link between the artistic experiments and the cultural backgrounds of the artists involved.

For instance the performance “AHHA”, a collaboration between the artists Nina Katchadourian and Ahmet Öğüt, follows up this incitement through a brilliantly balanced critical enactment but also parody of the significance of cultural exchange and public diplomacy.

The two artists are of Armenian and Turkish-Kurdish descent respectively, and have made a public judicial contract to exchange the letters “A” ad “H” in their names, in a process similar to an organ donation or blood transfusion. “Both Katchadourian and Öğüt value the letters in their names, because they consider the letters to carry with them the unique qualities of ethnicity, history, culture, pronunciation and family lineage that Katchadourian and Öğüt define uniquely and particularly. Therefore they do not consider the two letters “A”s to be identical, by virtue of the different pasts that have brought about the name that contains the letters” the legal declaration states. During a ceremony (the exhibition opening at Pratt Manhattan Gallery) assisted by a public notar, the letters “A” were exchanged, under the reading of the same statement. The “H” will be exchanged at a point in future after their deaths. In addition, the ceremony is set to take place once more in the future, between two persons carrying their exact same names, but who must carry it out on their own initiative, by exchanging their letters “H”. If no-one chooses to fulfill this task, the artwork will remain in eternal suspension.

In all its technicality, there are potential layers of poetry as well as parody in this artistic performance. The invisibility of the act clarifies the often mistaken expectation that cross-cultural encounters are bound to make real differences visible. But just as invisible is the extent and nature of the artists' own identification with these names and letters, even though they might be seen as carriers of history. This uncertainty challenges any determinism concerning the role played by culture in artistic performances in the first place. Similarly, the act of leaving behind part of one's name seems to emphasize the fact that a new commonality results from working together, and how such an act constitutes a future-oriented trajectory of change and renewal which the actors become responsible for.

In an alternative perspective “AHHA“ can be read as a parody of political treaties made to bridge differences that are supposedly real, to open up a reflection over the grounds for continuing to accept such differences, as well as the form and function of the historical narratives they are based on. This last mentioned interest is shared by many of the participants in Blind Dates, and in very different ways. Michael Blum and Damir Niksic’s short film Oriental Dream is a slapstick story about two guys running around in Sarajevo fighting over possession of an Ottoman fez, evoking absurdly persistent cultural clichés about East and West as well as how the fall of the Ottoman Empire became a source of conflict. Hrayr Eulmessekian and Anahid Kassabian question the representability of traumatic events, like genocide, as historical facts, and raise the question of how to mourn something whose essence is both beyond reach and beyond the limits of language itself. In a similar way, Jean Marie Casbarian and Nazan Maksudyan’s works critique the exploited verisimilitude of documentaristic and archival practices in the production of historical narrative.

Cultural restoration in a zone of stalemate

Many of the works in the project directly or indirectly refer to the current stalemate of negotiations between Turkey and Armenia, which persists despite several recent attempts at rapprochement between the two countries. Adding to Turkey's unwillingness to acknowledge the Armenian genocide is the disagreement over a number of formulations in the now deadlocked diplomatic roadmap that was agreed upon in 2009, such as the retreat of Armenian forces from some of the regions occupied during the war with Azerbaijan in the early 90's, and internal Armenian disputes on whether or not normalization of relations (i.e. formalized diplomatic relations and opening of borders) should depend on reclaiming the established borders with Turkey from the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres (which was never ratified by Turkey). On top of that comes a rhetoric of mutual denunciation. As late as January 18, the Armenian president expressed that 'A country that, since Armenia gained independence, closed our border on various pretexts and is trying to blackmail my people, may not aspire to regional leadership,' and characterized the country's geopolitical agenda as 'Neo-Ottomanism'.

The need of alternative forms and approaches to supplement the language of geopolitics and diplomacy has long been acknowledged by cultural representatives on both sides of the border, and as an important step in the direction of moving forward they have focused on the restoration of common cultural and archeological heritage sites. Given the contemporary situation, restoring these sites may in itself be seen as an incitement and act of responsibility to reach a common understanding of the past, and move forward based on a new sense of the shared historicity of the ground. In other words the question of how to restore and present archeological ruins, becomes a question of interpretation. To avoid the reduction of the sites to museological and touristic interest it seems that both their renewed practical use (e.g. of churches) and the very process of imagining different architectural forms of reflexivity, are at least as significant as conventional forms of dignifying make-up of historic facades and ruins.

The bridge at Ani

Two projects central to Blind Dates take a brand new look at the terrains and historical sites in the border areas between Turkey and Armenia. 'Remains connected' is a collaboration between architects Silva Ajemian and Aslihan Demirtas, who take the remains of the broken bridge at Ani as their point of departure. Once a glorious Armenian capital, Ani is today a ghost town where two narratives compete: one of contemporary geopolitics and one of archeology. Until recently, however, very few remains bore witness to the former greatness of the site, and all references to Armenian history had also been carefully omitted. First mentioned in historical sources in the 5th century AD, Ani later prospered as the magnificent capital of the Armenian Bagratuni dynasty after 961, and became the seat of the Armenian Catholicosate in 992. In the following century it became known as 'The city of forty gates' and 'The city of a thousand and one churches.' After an intermittent period of invasions, instability and war, the Zakarid dynasty marked a second, prosperous period in the city's history between 1199 and 1226, when many of Ani's important churches and historic buildings were constructed, and its status as a cultural center and important trading hub was reasserted. In the following centuries, under the rule of shifting dynasties and later the Ottoman Empire, began its steady decline towards a scarcely populated ghost town. After it became a part of the Russian Empire in 1878 began the first comprehensive archeological excavations to understand and preserve Ani's history. After the shortlived Armenian Republic declared its independence in the late stages of World War I, Ottoman forces reoccupied Kars and a number of artefacts were evacuated to Yerevan, while the rest were destroyed or stolen. Once more, after the Turkish Nationalists' rejection of the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, Atatürk's forces invaded the country. In May 1921 the Turkish National Assembly issued a command that the 'monuments of Ani be wiped off the face of the earth'.

The question which the Ajemian and Demirtas' architectural sketches state is: what do we really see when we come to such a city in ruins; and what can we see here, if our optics is informed not only by contemporary political disputes and geographical borders and names, but by the environment as history and nature at the same time? And more importantly, how can a comprehensive, imaginative outlook on geography lay the ground open for future prospects without disregarding visible wounds?

Among other things, the architects envision possible new configurations of the broken medieval bridge over the Akhurian river, which is today mostly seen as a symbol of the Turkish-Armenian relations. They have transfigured the remains and their interaction with the surrounding landscape into a layered, binocular vision, where their sketches, visions and photographs become interwoven. At first glance what seems to take place is a transition and enrichment of the symbolic value of the geography. In one example, two photographs are combined within a frame, divided by a clear separation. On the left part of the composite image, we gaze at the Akhurian river and the flatlands that surround it, perhaps through a window in one of the surrounding stone ruins. Mirrored or plunged into the river, the ruins of the bridge can also be seen. Imagination seems to ambiguously implant the physical scenery between memory and melancholia on the one hand (ruins of a civilization), and on the other, the flow of the river which connotes the continuation of life's flow. The image centers on the vertical displacement of the river, and its vanishing point. In the second part of the composite image, on a black background, we find an architectural drawing with light, colorful lines like stitches to close a wound across the gap where the river flows. These lines signify physical channels that are supposed to be cut off at the cliff on each side, stretching towards each other through invisible lines in the air, connecting the river banks. Future seems to become alive here, as part nature, part imagination.

Botanical regress

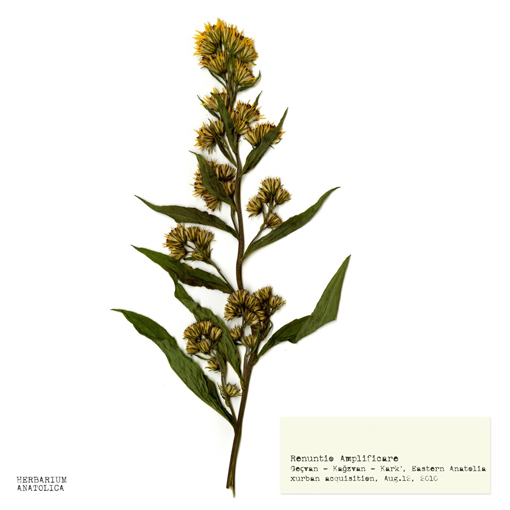

The second project concerning Anatolian geography consists of Botany Carcinoma and Building Blocks by Istanbul-based Xurban Collective. Hakan Topal, one of the artists in the collective elaborates on their presentation of images of Anatolian landscapes, which joins a large number of similar territorial investigations the collective has been involved in over the last 10 years, from Turkey and elsewhere: “I am not a historian. I feel closer to archaeology. Archaeologists analyze the objects of a locality (...). Looking at the landscape in Anatolia is a political act. Whatever you see is layers upon layers of unwritten history… where the earth becomes a sort of dissident too.” One of the projects, “Building Blocks”, examines remains of homes in ‘abandoned’ Anatolian villages to add a perspective to contemporary issues: “For me, the outcome of this project may be to understand the possibility of justice, or the impossibility of it. (...) Until recently large sections of Anatolian population were not being recognized as cultures or nations. Where are the people whose traces remain in these same landscapes that exist to this day? Why don’t professional archaeologists consider these remains in Anatolia worthy of study? Archaeology used to rely on creating a kind of “rupture” in the earth to uncover certain facts about the past. This type of work is now considered a criminal act in Turkey. Today, non-intrusive methods must be utilized. Our project for Blind Dates aims to look at things from a geological timeline in order to understand the Anatolian landscape in terms of its ruptures and fault lines” he explains.

In Botany Carcinoma the collective has taken a radical step back in geological history, which ironically demonstrates both the hope and hopeless conditions of writing a more recent history of the area. Adventuring through the area taking pictures of landscapes, nature, plants and flowers, they take as their “map” and point of departure the rudimentary descriptions of the geography made by Strabo of Amaseia about 2000 years ago, and combines this with an inspiration from the French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, who in 1701 traveled to North-Eastern Anatolia to collect samples for his herbarium at Jardin des Plantes in Paris, which he later scientifically named. In their own way, Xurban also names flowers and plants they find on their journey.

The procedure is rather ambiguous in itself as it can be called a simultaneous repetition and archeology of the act of producing history and geography; the act of description, scientific naming and division into meaningful categories pertaining to a certain era, flora and territory. Such acts, even though they may take their cues from site specific observations and names, are in Xurban's retroactive work linked to the multiple, original acts of creating scientific or political divisions in this landscape and between people. They point to the fact that such acts did not take into consideration the altogether different meaning attributed to nature and surroundings by people originally living in the area, and who were later alienated from each other in quite similar procedures, but on a larger scale.

The consequence they draw from today's locked history is a kind of willed oblivion, a return to pure sensation and errant travel experiences. The paradox of this radically experiential procedure, reminiscent of early modern travel journals into unrecorded territory, seems to lie in the combination of meaninglessness, as the perhaps impossible attempt to return to a pre-signifying stage, and at the same time meaningfullness, as a kind of hope, as a valuation of the unexaminable fullness of the geography which is revealed as preserving its own tacit memory in this journey.

The question remains whether this kind of blindness, of willed oblivion, has a future potential. The blindness of the Blind Dates Project also consists in being an unfinished project which has still not produced an ultimately coherent exhibition. As the project evolves after it started in Pratt Manhattan Gallery earlier this year, it will reach Yerevan and then Istanbul in the spring and summer of 2012, before it is planned to reappear in galleries across the US. In the meantime the contributions to the Blind Dates Project can potentially be read as unfinished signs hope.

For more information, the project home page can be visited at www.blinddatesproject.org