July 1, 2011

One day it will have to be over

Revisiting Art and Politics in Brazil

By Paal Andreas Bøe

One day it will have to be over is the second in a series of three exhibitions at Museo de Arte Contemporãnea in São Paulo (USP) which deal with the conditions of art in Brazil during the military dictatorship, covering three different periods: 1964-1968; 1969-1974 and 1975-1985. The periodization corresponds to the establishment, recrudescence and distention of the regime. During its reign, the newly founded USP was also the only art institution in the country that was able to continue its function as a meeting place for artists critical of the regime. Under such political conditions the museum managed to reinvent the whole idea of the modern art museum by turning it into a social space and tearing down the borders between inside and outside, much thanks to artists like Regina Vater, Constantino Ignacio Riemma and Gastão de Megalhães, among others. During the 6th Young Contemporary Art Show (1972) Megalhães dug up the lawn of the Museum garden and transported it inside, in a performance that became emblematic of this transformation. But also more generally, the 60s and 70s in Brazil were characterized by latent artistic discourses in which new, de-materialized strategies were set into life.

This period in Brazilian art history was remarkable because it represented a peculiar attentiveness to the question of the relation between art and society. Understandably the introduction of censorship, torture and persecution of dissidents under the new regime served as a catalyst for this attention. But the ground was also in a different sense prepared for it since the question had been at the center of artistic and intellectual debate at the very breakthrough of the coup of 1964, just a year after the establishment of USP. A search was already then going on for new ways of thinking art as politically and ethically significant, opposed to the ideological and nationalistic art that had been prescribed by the orthodox left. The artists and intellectuals representing this interest often found themselves rejected from both left and right.

Unavoidably, the following decades of dictatorship were marked by less predictable strategies of protest and new ways of cooperation. More than ever mail exchange became a privileged form of artistic collaboration over borders, particularly with Eastern European countries where artists found themselves in a similar situation of censorship. These networks existed without regard to the international art market and its cosmopolitan centers. National, public communication and circulation systems also became re-appropriated as means of artistic communication and expression.

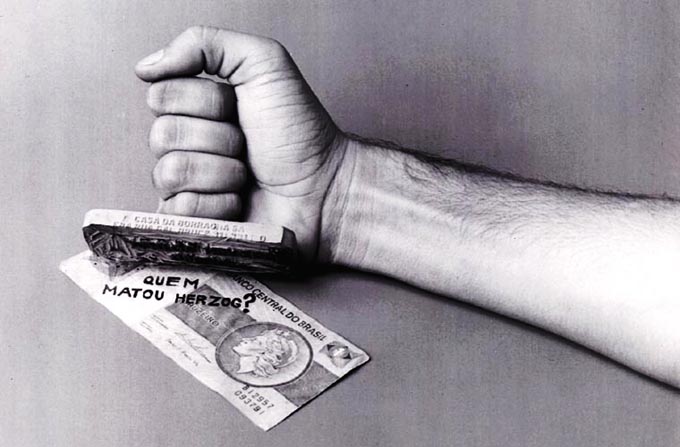

In Cildo Meireles' projects Inserções em circuitos ideológicos (Insertions in the Ideological Circuit), provocative phrases were stamped onto money notes that he released back into circulation, such as “Quem matou Herzog?” (“Who killed Herzog?”). This was after the death of the Brazilian journalist Wladimir Herzog, killed under torture by the military government, but officially proclaimed to have committed suicide. In another project Coca Cola bottles, the main symbol of American imperialism at the time, were imprinted with the words “Yankees go home”.

More than an efficient means of spreading various clandestine messages at a time when the artist-subject was forcefully erased as the artwork's intentional center, Meireles' works also became self-conscious goods and exchange values. As such, their function would have been strongly inhibited if isolated from a public, practical reality, in a local historical context. Yet paradoxically the very “protest” of recirculating them was a combined repetition and negation of their value at the same time. They became dualistic objects, self-reflexively manifesting the same violent discrepancies and tensions that they contributed in real life, between the abstract, intangible instruments of a CIA-endorsed militarist dictatorial power on one side, and its particular, human, situated consequences and possibilities of revolt on the other. As such, they mirrored a tension visibly residing within art itself, as posited in between free expression and ideology; between spontaneous, living expression and the expression of a totalitarian state and a blindly wounding capital.

Within the “Neo-concrete” movement which emerged from Rio de Janeiro, these new artistic tendencies were combined with an opposition to institution art and the rationalistic, technological, geometrically abstract approaches of the influential Sao Paulo-based Concrete movement. The Neo-Concrete manifesto, written by Ferreiro Gullar, was published on the 22nd of March 1959 in the Jornal do Brasil newspaper, signed by Amilcar de Castro, Franz Weissmann, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, Reynaldo Jardim and Theon Spanudis. A central postulate of the movement was that no theory could be prescribed for works of art – that theory could only be posterior to the act of creation. Particularly influenced by Merleau-Ponty, whom Gullar himself introduced, the group sought to overcome the barrier between art and life through subjective and expressive approaches in which the artist's and the spectator's bodily and sensory participation in the work of art was evoked, at the same time as the borders of the institution were challenged.

In all his idiosyncrasy Artur Barrio is somewhat exemplary of the phenomenological penchant of the movement. Among other things Barrio is famous for defamiliarizing and profoundly chaotic constellations of 'insignificant' everyday objects, smells and organic materials, often in an ephemeral state of transition such as the ”blood bundles”, cloth filled with parts of dead animals that he left in the streets of Rio de Janeiro to observe how passers-by reacted to them, or his less macabre yet also conspicuously left behind bundles of bread (...). Barrio's polymorphisms tend to resist objectification, involving instead the spectator in sensory encounters which suggest a primordial fullness of reality: ”What I look for is a contact with reality in its totality, everything that is rejected, everything that is set aside because of its contentious character. A contention that harbors a radical reality, because this reality exists, despite being dissimulated through symbols”, he explains. In the context of the 1960s his works were iconoclastic gestures targeting the reality-images of the ideological perception, hence their political significance resided in the very irreducibility of their reality shock.

However “Neo-Concretism”, while having a great impact on Brazilian art of the 60's and 70's, did not become the coordinated movement it might seem to be at first. Artists like Castro and Weissmann, because of their upheld interest in working with space through formal experiments, were seen as representing a peak of, rather than a break with concretism. To the surprise of many its founder, the poet and critic Ferreira Gullar, made an apparent u-turn by publishing the text “Questioning Culture” [...] in 1963, where he dismissed as bourgeois and elitist all art that valued aesthetic form over ideological content, thereby not only rejecting the group's initial “art before theory” postulate, but simultaneously also reinstating an ideological stance. At that moment, while Gullar had joined the Communist Party, the second main figure of Neo Concretist art Hélio Oiticica had become a dancer and joined the Samba School Estação Primeira da Mangueira. Far from a politically militant, suspicious of all kinds of organized groups, he was in several ways similar to his anarchist grandfather, the poet José Oiticica. He believed in art as a means of social change, and combined radical aesthetic experiments with a social and ethical interest. Oiticica managed to navigate between Mangueira Hill, one of the oldest shantytowns of Rio de Janeiro where he preferred to stay, and the lofty venues of the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro. However when he brought his dancing samba groups spontaneously into the museum wearing his famous parangolés, a kind of colourful cape that sometimes bore inscriptions, they were thrown out.