December 10, 2011

Details on contemporary fascism

Bergen Kunsthall September 9-October 30 2011

Curated by What, How and for Whom

Written by Paal Andreas Bøe

The exhibition Details at Bergen Kunsthall focuses on the political potential in art as an archaeology of the politics of perception: it specifically inquires about everyday repositories of contemporary fascism. But just how specific can we actually be in addressing such an issue today, and how can something like art play a role in this? What does such an exhibition mean in the current Norwegian, Scandinavian and Western European contexts?

Rasko Mocnik: capitalism as the turbine of European neo-fascism

In these days when instead of capitalism’s threats to civil society and global solidarity, the “battle of civilizations” has become the central political agenda and driving force in Western media, and also taken for granted as a part of everyday life; when the media in nearly all Western countries can (temporarily) get away with reducing the “Occupy Wall Street” movement to “youth racket” which they only mention once in a while to assure us that “police has now taken care of it” (by brutally attacking peaceful protesters, that is); at a time, also, when systematic secrecy redeems itself as a legitimate part of democratic nations, by boring us with its play of hide-and-seek – this small constellation of artworks provides a salient example of how artistic endeavors can be a tool, albeit limited, of analysis and critique. The exhibition takes its point of departure in the texts by Slovenian sociologist and activist Rasko Mocnik, who tied the conflicts and outbursts of fascism and nationalism in areas of the European periphery (from the Adriatic Sea to Siberia) in the 1990s, to the new introduction of a “peripheral capitalism”. Mocnik pointed out how racist cultural policies accompanied the new nation-building as a solution to the instabilities posed by the new economic order, and how "depoliticization", also in the form of “anti-anti-fascism” was a part of how public spaces were planned in the neo-liberal landscape.

This unsettling form of invisibility echoes in Milica Tomićs “One Day, instead of one night, a burst of machine-gun fire will flash, if light cannot come otherwise” (2009) which stages the annexation of public space and the current limitations to the rights to civil disobedience in Beograd. The work documents a number of strolls she made in 2009 to forgotten places in the city where anti-fascist protests were held during the World War II, the memory of which has largely been erased. In this video the artist carries a shopping bag and a machine gun as she walks through the streets; no-one reacting to it. The voiceover is a combination of interviews Tomić made with heroes from the anti-fascist movement in Beograd who took part in the historic events at the places she visits, and creates a grim contrast to the contemporary apathetic atmosphere caught on film. Her work is dedicated to a group of young members of the Anarchist-Syndicalist Initiative that during the days of recording were charged for international terrorism because they made protests in front of the Greek embassy, in solidarity with demonstrations in Greece.

Administered details – or the banality of fascism

By distorting and recontextualizing everyday perceptual phenomena from Israel, Serbia, Denmark, Turkey, Norway and the US into the hypothetical space of the gallery, the exhibition generally highlights how trivial “details” that appear uncoupled from ideology and political consequences, may in reality be fatally naturalized. At the same time it disquietingly reminds us of how the tendencies Mocnik pointed to have now taken a stronghold in a number of Western European countries, and of the invisible, administrative discipline and coding of life under neo-liberalism in general, which silently disarms any challenges to the status quo. Well helped by the media, the discourse of national security – in which the threats to our economic order are projected on the cultural other and fused with the terrorist threat – has gained the status as an absolute, and our prime political concern.

With a reference to the situation in France, Jaques Rancière recently pointed out that the racism we are facing today is not primarily a passion in certain parts of the population, but in the state apparatus – a “passion from above”. He points out the double agenda and rhetorical game of the state which pretends to be preventing the spread of racism from “irrational parts of the population” who react to crime and other nuisances caused by immigrants. The strategy exploits the myth stating that racism is a product of the working class, “badly educated” and irrational people. The solution is to reinforce law and order. The state uses precisely this rhetorics as an excuse for increased "identity management" – to continuously redefine the cultural identities of its citizens and reconsider which parts of the population are the “real French”. Unwanted groups are then deprived of their civil rights as European citizens and deported, or they end up with a precarious status meaning that deportation may become their fate sometime in the future.

This is a reminder of how racism can be camouflaged as a pragmatic, necessary administrative part of our social democracies, by politicians who, with good help from the media, construct enemy scenarios to pull our attention away from the damage caused by the economic order under which we live. At the same time they show off their responsibility by making security policies, administration of human groups and identities their main field of action. To supplement Rancière’s analysis of a “racism from above”, arguably the combination of the lack of political agency with regard to steering the global market economy, the focus on ”problem groups”, and on economic and security threats to the ”nation”, may contribute to precisely the kind of powerlessness concerning political representation, which fascism feeds on: with good help from the media, this may create a climate for secondary forms of racism and neo-fascist gestures to regain control over a fear-infused, overcomplicated reality.

Distortions of contemporary barriers: between consumerism and "passive" political violence

In various ways the artworks at Bergen Kunsthall distort and recombine everyday phenomena, making them conspicuously self-reflexive and apt to highlight the apparatuses – economic, political, technological, medial – through which everyday phenomena are normally conceived. The Turkish artist Burak Delier explores the hidden disciplining of citizens through consumer culture – for instance how research and marketing surveys are designed to exploit people’s desires to be able to steer our attention and lay a pressure on us which derails the formation of political opinion, and makes us accept the reduction of public city spaces to shopping malls, financial buildings and motorways. We are reminded of this in the video installation ”The Feasibility Research” (2010) which consists of marketing survey interviews with various marginalized members of Turkish society (Kurds, transsexuals, woman activists, left-oriented students). Bergen Kunsthall also displays products from his fictional company Tersyön (“Reverse Direction”), which is a company working against the damages of neoliberalism, to “protect those who want to defend their subjective and local values and those who attempt to write history in reverse against the clandestine and open violence of the consumption-focused pseudo-democracy of neoliberalism and nationalism.” The fictional company not only reveals the political advantage in consumer culture, but also parodies and distorts it into a counter strategy: the company produces equipment to protect citizens against the damaging effects of the neoliberal order, like equipment for civil disobedience; functional jackets for protesters with pocket for spray paint, handouts and newspapers, blow resistant hoods etc.

Avi Mograbi’s videos, the title work Details (2003-2011), are subjective acts to reappropriate both public space and technologies of representation, where the video camera becomes a civic, pacifist weapon. He documents the status quo of Israeli violations of civil rights and public power abuse that has since long become predictably unpredictable to a point of absurdity. In one of the videos, for instance, he confronts a group of soldiers who have barred a gate for the passage of a group of school children, claiming that they do not have to provide the reason for it, and without telling when it will be open even though their job is to keep the door open at scheduled times. This kind of “accidental” transgression of civic rights is just one example of the systemically implemented passive violence that Palestinians go through on a daily basis. Mograbi not only confronts the soldiers telling them to do their duty as public servants, and documents their actions and reaction to his defense of the right to keep the camera rolling until they can provide legal documentation to stop him, but he also uses the camera as his “weapon” to appeal to the human decency of the soldiers. We are obviously talking about a use of the media that is quite different from the majority of international news coverage.

Contemporary nationalism in Scandinavia

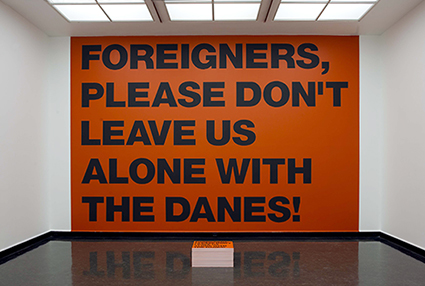

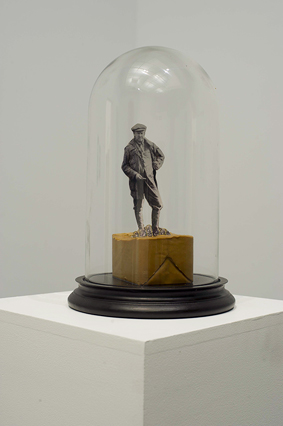

Against a red background Superflex’ monumental sign with black letters states: “Foreigners, please don’t leave us alone with the Danes”. It raises yet another blind spot to visibility: the situation of immigrants in Denmark, who over the two last decades have had no choice, but to try and survive under an increasingly accepted racist and nationalistic, xenophobic political leadership and public sphere. In this context Lene Berg’s combined “national monument” to Vidkun Quisling and Norwegian brown goat cheese (”Norwegian Products (Quisling and brown cheese in a glass container)”, 2010) – another revealing distortion – reminds us of how the Norwegian public and political sphere has become equally contaminated by an overtly racist and nationalistic discourse over the last decades, even though Denmark has managed to gain a larger reputation for it.

According to a fresh statistics 25 % of the population in Norway considers there to be too many Muslims in the country, and sees Islam as a threat to Norwegian culture. A couple of days ago, PST (The Security Services of the Police) proclaimed that the largest threat to national security was still Muslim extremists, and not the likes of Anders Behring Breivik, who for months has filled the major Norwegian newspapers with his carefully stylized images of himself as the stoic, triumphant warrior in a Lacoste outfit. This is not least the case for Norway's second biggest newspaper Dagbladet, which in addition to years of uncritical speculation in the fact that xenophobia sells newspapers, permits anonymous commentaries in their online edition that come close to neo nazi propaganda - no less after July 22.

Since the late 80’s when Carl I. Hagen launched an aggressive anti-immigration campaign based on a forged letter from Mohammad Mustafa stating that Muslims were ready to take over the country, the Norwegian right-wing party FrP (Progress Party), for which Carl I. Hagen was the chairman, has grown steadily and gained its highest position ever under the last parliamentary elections (2009), retaining 23% of the votes and becoming the second largest party after the Labor Party (AP). Its grim success in the most recent years has been largely built on the “euphemistically” (in comparison to its Danish sister party Dansk Folkeparti, which has lately been more explicitly racist) patronizing and resentful discourse towards the multicultural minorities.

Some fearing the implications of FrP rule, but everyone realizing the instrumental advantage of this strategy, parties from left to right began a competition race for the anti-immigrant vote under the flag of a “responsible immigration policy” in which FrP’s directly hostile outbursts towards “foreigners” was replaced by a rhetorics of pedantry towards the unassimilable (reluctant) other, whose “cultures” and “traditions” were to be taken seriously primarily as a disciplinary challenge (so-called integration), rather than a question of understanding and communication. Politicians had had enough of seeing FrP in the front seat, and saw the need to “responsibly” confront the “real issues” related to immigration: women’s rights, education, language etc. While in some aspects this untethering of what had until then been largely a taboo to the parties of the Left, made it possible to shed light on real challenges to integration, the product of the politicians’ new spectacle of responsibility has nonetheless been a reinforcement of prejudices concerning entire groups, and as such contributed to the legitimacy of an attitude that immigration rules need to be kept tight and merciless.

It would be very misguided to blame the rise of xenophobia entirely on FrP, even though this party triggered and has played a key role in it. Neither is it sufficient to blame it on the short-sightedness of the citizens who voted for them. The underlying reasons lie elsewhere. Meanwhile, the media and other parties definitely share a large part of the responsibility for letting FrP lay the premises for the political landscape in Norway. This has become a landscape in which politics has steadily been cast to suit Scandinavian neo-liberalism; the privatized and fragmented consumer-reality of isolated, ultra-rich countries in which we “shouldn’t really have to bother about anything”, and in which politics is about generating rage towards singular exceptions and more or (often) less serious threats to our national privilege of individual comfort – and most effectively, as everywhere in Scandinavia and Western Europe, towards “security threats” represented by abstract “alien elements”, irrationally projected on the “shockwave” of asylum seekers, or the “hidden darkness” of the culture and religion of the Muslim communities.

This is also strikingly reminiscent of the situation Rancière points out in France: the spectacle of responsibility pretends to defend the “fundamental values and laws” of our social democracy, with which duties and rights follow, yet it also forcefully evicts anyone not fitting the politically changing identities administered by the faceless, slow-pace bureaucratic machinery to which “responsibility” has been delegated, no matter how long some people may have lived temporarily in the country to wait for the final answer, to know whether they have the right to stay or not (we’re talking up to many years), and often despite well documented probability of imprisonment without trial and torture being the consequence for people that are deported. Norwegian authorities have also been severely criticized by the UN High Commisiononer of Refugees (UNHCR), for breaching the UN Convention of Refugees. Presumably, this is to discourage anyone from “trying the same luck”, but it is also an efficient way of redirecting our focus at a time when politicians do not wish to (or do not have to, as long as oil money keeps flowing in) address the real flaws of our economic system, that if taken seriously, would not just reveal political helplessness and lack of real representation, but ought also incite a hitherto inexperienced international solidarity.

In the meantime, the ruthlessness of the “preventive” anti-immigration measures appears justified by the “disciplinary challenge” posed by larger segments of the immigrant population who have managed to obtain a citizenship. Never has the hypocrisy in the politically opportune “integration efforts” been more completely evident than during a televised debate about radicalism in Muslim youth communities last winter, when the full spectrum of high-level representatives from the largest political parties in Norway had the chance to face leaders and workers from multi-cultural youth organizations and field volunteers to talk about factual challenges to integration, as these people experienced them in the everyday life. One should perhaps not be astonished, but during the 60 minutes of the program there was not one single, serious effort to listen and communicate – only the usual spectacle of responsibility: “do your duties, get your rights – and remember we do not tolerate the repressive traits of your culture. What have you done to fight terrorism?”.

In this context, Lene Berg’s work is a trivial, minimalist wake-up call for our national history: as mentioned it insists on the relation between two “Norwegian products” – the national symbol of the brown goat cheese, and a paper figure of the leader of the nazi government (NS) during occupation, Vidkun Quisling – by letting Quisling throne on the cheese inside a fully closed glass cylinder. A second part of the work juxtaposes two framed “announcements”, the first stating that “All cinemas will be closed tonight due to Vidkun Quisling’s speech at the University Square” and the second, a commercial for Norwegian brown goat cheese: “Brown cheese is what makes us Norwegians Norwegians”.

At first glance, the work makes a simple rhetorical point of questioning the idea of a national narrative and its day-to-day functioning; how our fixation with symbols effectively dissimulates failure and dark parts of our history that are not compatible with an official version, at the same time as it generates unfounded national myths and cultural prejudices. At the same time, the dialogue between the different modes of presentation of the two parts of the work, also questions the form of latency of fascist outbursts and the difficulty posed by modes of representation: it surfaces how consensually accepted forms of historical narrative may in themselves serve to conceal, if not trivialize fascism’s roots and even create a climate for a new brooding, depending on the circumstances. As far as Norway’s concerned, the oil pumped into our national narrative since the 1970s founded the fiction of a new “national adventure” which has been an effective means of forgetting and gradually alienating the rationality of international solidarity and cooperation. And even if our situation with nation state turbo-capitalism and battle of civilizations flagged under the banner of social democracy is very far from direct fascist rule, a by-product of this situation may be to generate feelings of chaos, powerlessness and lack of participation and easily manageable cultural representation that are more violently projected on “invading forces”. It may generate kinds of desperate gestures to regain cultural and political power and control by imposing new forms of uniformity and hierarchy, similar to the horrific events in Oslo this summer.

The politics of vision

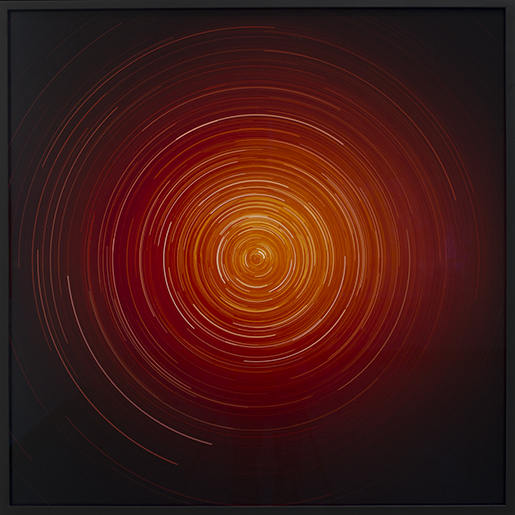

Hidden control mechanisms are addressed in a different light by Trevor Paglen, who has for years spent time regularly in a desert valley on the northern shore of California’s Mono Lake, where he has photographed the nearly two hundred US reconnaissance satellites whose existence is unacknowledged by the US military, but whose position he has been able to predict with the help of amateur astronomers. His works are remarkable in that they demonstrate how contemporary fascism is not necessarily about negative forces which can be localized, but also to a large extent employs its own pan-optics; ways of seeing that are remarkably integrated in, produced and distributed by the technologies of vision.

Paglen sees himself strangely related to the American frontier photographers of the 19th century. He says that spending so much time in desert valleys gave him an opportunity to think about the geographical history (Paglen has a PhD in Geography from Berkeley, where he normally works as a researcher) of these “blank spot” territories as they were formerly represented by photographers such as Timothy O’Sullivan and Carleton Watkins in joint mission with scientists and government surveyors as part of a process of mapping, settlement and exploitation, and hence also: the creation of a pan-iconography of the American landscape. As Paglen states in an interview [i], photography thus became intimately linked with the colonization process, in a historical development that is directly linked to today’s regime of covert satellite systems and secret operations that are not external to, but precisely part of, the empire: “Ideologically and technologically, today’s military and reconnaissance spacecraft are directly descended from the men who once roamed America’s deserts and mountains photographing blank spots on the map”. In Paglen’s photography, however, these blank spots have become the unofficial satellites and spacecraft – the colonizers themselves.

Fundamental to the aesthetics of frontier photography was an idea of the sublime, in which the pioneer photographers drew heavily on the history of painting, like the metaphysically suggestive depictions of the maritime sublime. Paglen combines this tradition with references to Stieglitz’ use of clouds, in which the sublime was, in a different technology, to make the insensible perceptually sensible, and hence to suggest the unmapped spaces of subjective, imaginative freedom. This combination constitutes a self-reflexive strategy, an ironic deployment of the aesthetics of the sublime, highlighting survey photography as a geographic imagination of otherness in which feelings of fear, pleasure and the will to colonize were enticed and made to interact exponentially. It evokes how photography, both as pictorialist aesthetics and as an act, became a tool of mastery, orientalist pleasure and symbolic violence through mapping and documentation.

In the quoted interview, Paglen also reminds us of how the intimate link between photographic documentation and warfare became grimly explicit in Harold Eugene “Doc” Edgerton’s development of a technique, based on Muybridge’s motion studies, to photograph nuclear explosions with light-speed strobe cameras. Realizing that the technical difference between documenting the explosions and triggering them directly was very small, Edgerton transformed his enterprise into an advanced photographic detonating system and became a major US military contractor. This violent combination of aesthetic perception and technology - also a prolongation of the aesthetics of the American survey photographers - was the epitome of a different, “technological sublime” in the cold war-era: a technologically inflated and transfigured imagery of power and will to destruction of an earthly enemy. At the same time this aesthetics, which evoked unbearable fears of world-annihilating war, found a balance in the cosmic fantasies of triumphant colonization: a sublime dream "made real" both scientifically, optically and politically by the moon landing.

Paglen’s work is not primarily about the fact of mutual surveillance, neither about the link between photography and warfare per se. First and foremost, the photographs are a mise-en-scène of the technological sublime, presented as an ironic relation within its own perceptual-political tradition. However, the originality of Paglen's approach is not the least how he implicates the viewer in this way of seeing, which once iconified the orientalism towards the imperial other (Indians) in sublime terms, and which has now withdrawn into this same sublime opacity through which it once projected its own fears and longings for mastery. Paglen reinserts the viewer as the master of this perceptual technology, and thus forces him to encounter the history of his own gaze in the American night sky, and to ambivalently acknowledge the potential destructiveness embedded in the gaze. Yet crucially also, he visualizes the potential for a critical reappropriation of optics, and a redistribution of vision and space. It is in this sense also that Paglen conceives the productiveness of his work as art, because “If human activities are inextricably spatial, then new forms of freedom and democracy can only emerge in dialectical relation to the production of new spaces.”

The art gallery as a laboratory for the politics of perception

To follow up Paglen’s thoughts, it can also be claimed that much of the political potential in the art gallery today is to be a microlab for different types of experimentation with our habitual perceptual and spatial concepts, something Bergen Kunsthall also follows up. In many ways Bergen Kunsthall makes the art gallery’s contextlessness suspicious – in the way it has been naturalized by the contemporary art economy, and turned into yet another apolitical part of the neoliberal public sphere, one might add – but first and foremost the “contextless” everyday details that are distorted and combined into a productive speculation. However, the exhibition could to a larger extent and more directly have challenged the visitors’ bodily presence through experiments with the political perception of space, since precisely the depoliticized space is such a central theme in the exhibition. Artists like Paglen and Mograbi, who so originally and emphatically politicize the technologies of vision, could for instance have been supplemented with curatorial steps to address the body’s spatial existence as a basis for the politics of everyday perception. The closest one gets to such a confrontation are Burak Delier’s jackets, but in this context the potential is somehow unfulfilled. The exhibition is more like a catalog of artistic political strategies, which refer to and supplement each other.

However, a perhaps paradoxical strength in this exhibition is the fact that it may just as well be conceived as too speculative and not enough speculative. This provokes an experience of ”bothersome in-betweens” which is definitely fruitful: it appeals to contextualization of everyday details, across constructed geographical distances, cultural and political separation lines, and it not least questions such separation lines in themselves – the nation state par excellence: its ability to camouflage the damages caused by neoliberalism beneath the production of new, politically advantageous enemy scenarios and conflicts.

[i] See Artforum March 2009, pp 225-229