December 10, 2011

The Political Matrix

The 12th Istanbul Biennial

September 17 - November 13

Curated by Jens Hoffmann and Adriana Pedrosa

Written by Paal Andreas Bøe

This year’s Istanbul Biennial deconstructs the idea of the art space architecturally, and simultaneously reclaims it as a pure function of the visitors’ bodily and intellectual possibilities of navigation.

This is also a rare and timely example of a biennial without comprehensive user manuals recommended by the curators in advance. Both in the exhibitions and in the text material (which almost entirely consists of the curators’ interviews with the artists who participate with solo shows) the biennial question and theoretical directions are so consequently absent that it is tempting to stamp it as a post-biennial where the curator’s death and the artist’s rebirth are proclaimed. Or rather, it is projected on a single artist figure as a thematic structuring principle in the exhibitions: the Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, of whom we do not find one single work, but who has in return inspired the title (Untitled) of the entire biennial, as well as the titles of its five group exhibitions: Untitled (History), Untitled (Death by Gun), Untitled (Abstraction), Untitled (Passport) and Untitled (Ross). The curators Jens Hoffmann and Adriano Pedrosa explain that they have primarily been inspired by Gonzalez-Torres’ combination of politically engaged and formally innovative art, and that they like him consider titles to be meaningless since meaning is aways changing in time and space. Gonzalez-Torres himself is often associated with an artistic expression in between post-minimalism and conceptualism, where he turns high-modernist and minimalist forms into expressions of pressing, personal and political agendas.

Apart from the 5 group exhibitions, the biennial consists of 50 solo exhibitions which develop and elaborate upon thematic and formal perspectives from the group exhibitions. Most directly inspired by the artist’s biography is the group exhibition Untitled (Ross), which takes its name from Gonzalez-Torres’ partner Ross Laycock, to whom he dedicated a number of works after he died of AIDS in 1991, 5 years before the artist himself. This part addresses the visual space of representation of homosexual forms of cohabitation and the possibility of representation in a heterosexual visual culture– both in a historic and a contemporary perspective. This is the case in, for instance, Elmgreen & Dragset’s The Black and White Diary, Fig. 5 (2009), which is a collection of 364 black and white photographs from domestic and informal settings, framed in white synthetic leather and exhibited on a long row of over-filled shelves. George Awde’s photographs of Libanese men, are taken in a hair dresser parlor and a pink living room, without any explicit ”explanation” to the relation between them. The room as a whole opens up a space in between the hegemonic heterosexual (and apparent for example in Awde’s works) western visual narratives about sexuality that the works respond to, and alternative possibilities of representation. In the neighboring space, we find a solo exhibition by South African Ardmore Ceramic Art Studio who use local traditions of ceramic sculpture and folk tales in Zulu culture to normalize the theme of AIDS, which in South Africa was an official taboo for a long time.

Rethinking abstraction

While Untitled (Ross) is the room which is most directly inspired by Gonzalez-Torres’ biography, Untitled (Abstraction) is the one which is most evidently inspired by his vision of art, his post-minimalist rethinking of abstraction, and most particularly, his questioning of the matrix as emblematic of what Rosalind Krauss called the will to silence and enmity towards narration in high modernism. Many of Gonzalez-Torres’ works characteristically ”infect” minimalist and abstract forms with personal and political questions, and dissolve the aesthetic autonomy of the matrix. One example is Untitled (Bloodwork – Steady Decline), a pure, classical matrix with a diagonal line stretching from the upper left to the lower right corner. The picture was presented as a representation of an HIV-infected person’s steadily deteriorating immune system.

The curators have made this tendency from Gonzalez-Torres the founding idea of an entire floor in one of the two exhibition buildings (Antrepo 5), Untitled (Abstraction), which is also the most tightly curated space of the biennial. The art-historical origin behind the rethinking of abstraction which Gonzalez-Torres’ post-minimalism represents, is particularly the Brazilian Neo-Concrete movement’s critique of institution art and of the Concrete movement’s emphasis on pure geometric shape which dominated Brazilian art in the 50s. The biennial presents many brazilian artists from the  movement, both front figures such as Lygia Clark and young successors such as Theo Craveiro. Formicary – Visible Idea (1956/2010) is an ant farm in glass where Craveiro repeats the pattern from a well-known abstract painting by the concretist Waldemar Cordeiro. I met Craveiro in the exhibition on the day before the opening, while he was working to improve the growth conditions of the ants using fruit and plants. He wanted the ants to exploit the glass frame as much as possible, but wasn’t particularly pleased with the activeness. Perhaps he dreamt that the ant society – a life form on which we often project our own rational models – sooner or later would occupy the box’, if not the entire biennial’s matrix?

movement, both front figures such as Lygia Clark and young successors such as Theo Craveiro. Formicary – Visible Idea (1956/2010) is an ant farm in glass where Craveiro repeats the pattern from a well-known abstract painting by the concretist Waldemar Cordeiro. I met Craveiro in the exhibition on the day before the opening, while he was working to improve the growth conditions of the ants using fruit and plants. He wanted the ants to exploit the glass frame as much as possible, but wasn’t particularly pleased with the activeness. Perhaps he dreamt that the ant society – a life form on which we often project our own rational models – sooner or later would occupy the box’, if not the entire biennial’s matrix?

The same deconstruction of the matrix is present in other nature-oriented works, such as Gabriel Sierra’s still life with fruit – meticulously bundled on a plate in between a matrix of rulers that seem ready to fall apart. Once again the matrix is revealed as a border phenomenon and intersection between the spheres of the human body, rationality and nature. The same is the case in Adriana Varejãos work Wall with Incisions à la Fontana, Istanbul (2011), where she recreates Lucio Fontana’s incisions as deep and bloody wounds in the matrix of the canvas.

However it can be discussed whether both the formally innovative and the explicit aspect is somewhat exaggerated in the curators’ claim that this biennial differentiates itself precisely by combining the formally innovative and the politically explicit. Measured against the level of ambition, but also generally, many single works leave a first impression of being, if not banal, then (too) easily readable and at times predictable in the context. On the other hand, the exhibition particularly succeeds in giving the visitor the feeling that perception and sensation is fundamentally political, as one moves through and between the exhibition spaces. Like in Untitled (Ross) this happens as the discrepancy between ”free subjectivity” and official, repressive narratives becomes highlighted as a space of possibilities for critique, bodily protest and experimental reconstitution of meaning.

The political space of the senses

Ryue Nishizawa’s exhibition architecture strongly contributes to this, by encapsulating all the walls of the rooms by the kind of metal walls that are  normally found at construction sites, and which create labyrinthic passages between the rooms, like the alleys in a city space – or, if one prefers, like an urban matrix. Despite the simplicity of the metaphor, the result is compelling in that it lets the visitors bodily acknowledge that the space is in essence a space to be constructed, and in which one is co-responsible for the production of meaning.

normally found at construction sites, and which create labyrinthic passages between the rooms, like the alleys in a city space – or, if one prefers, like an urban matrix. Despite the simplicity of the metaphor, the result is compelling in that it lets the visitors bodily acknowledge that the space is in essence a space to be constructed, and in which one is co-responsible for the production of meaning.

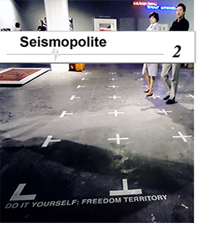

This appeal to bodily reconstitution of political space is noticeable both as an interplay between the works, and in the dynamics between the architecture and the works. Untitled (Passport) is a good example. This room deals with geographical borders, national and ethnic identities and challenges the hegemonic western definitions of the world. Immediately upon entering the room, the very question of freedom of movement becomes a direct physical barrier in Antonio Dias’ Do It Yourself Freedom Territory (1968), a white painted, interrupted matrix on the floor. While in Adriana Varejãos photography Contingent (2000), a hand crosses a light grey stone wall with a red line entitled ”equator”, also attributing the responsibility for a world of geographical possibilities and limitations to the human body, the hegemonic western worldview is literally reversed in Joaquin Torres Garcia’s América Invertida where the American continent is turned upside down while South America is twisted 180 degrees horizontally.

One is also compellingly reminded of the link between physical and abstract barriers, and the construction and administration of otherness, as one leaves behind Dias' open freedom matrix and walks over to a number of works which include passports and different forms and papers of identification. One example is Sue Williamson’s work For Thirty Years Next To His Heart (1990), where she has made a ”biography” from the ID cards which black South-Africans had to carry during apartheid.

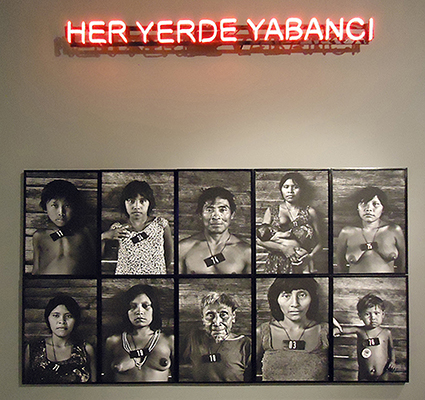

Claudia Andujar’s photographic project with Yanomami-indians from Roraima in Brazil (Marcados, 1981-83) repeats the method of identification which in the 19th century was used towards this group because they did not speak Portuguese: a necklace with a number badge around their neck.

The overall effect of making the political sensible is also forcefully present in the room Untitled (Death by Gun), which uses images and installations to repeat and distort well-known media depictions of violence and murder, but also exploits the large format of the exhibition to alienate the dimensional proportions between subject and object. A striking example is Mat Collishaw’s Bullet Hole (1988), in which 15 frames depict what appears to be a bullet hole in the back of a person’s head. The exaggerated dimensions of the work forces the perceiver into an ambiguous position, apt to create a physical discomfort and a critical distance to the trivialization of murders through the media. The effect is all the more stronger as the glass surfaces, reminiscent of church window panes, seem to invite a perverse religious worship of icons over the suffering of others.

Historical coups

Untitled (History) problematizes history writing as a cultural construction, appealing more to readability and less to displacement. Meanwhile, the room creates intimate experiences of the collision between subjective everyday experiences and official history writing. Jonathas de Andrade’s multimedial timeline of images and texts he has found in garbage in his hometown Recife, creates a complex urban fiction of forgotten elements and moves between personal and journalistic documentary of his hometown. Andrade says the project started when he became interested in the accellerated erosion that took place as increasing parts of the city, a ”failed project of modernism” according to him, was demolished to lay the ground ready for real estate speculation. The work makes visible the hidden lifeform and natural ”drive” of the city which always preserves its own tacit memory and personal histories, and survives all the attempts to invade it with short-sighted radical visions of urban renewal.

Untitled (History) problematizes history writing as a cultural construction, appealing more to readability and less to displacement. Meanwhile, the room creates intimate experiences of the collision between subjective everyday experiences and official history writing. Jonathas de Andrade’s multimedial timeline of images and texts he has found in garbage in his hometown Recife, creates a complex urban fiction of forgotten elements and moves between personal and journalistic documentary of his hometown. Andrade says the project started when he became interested in the accellerated erosion that took place as increasing parts of the city, a ”failed project of modernism” according to him, was demolished to lay the ground ready for real estate speculation. The work makes visible the hidden lifeform and natural ”drive” of the city which always preserves its own tacit memory and personal histories, and survives all the attempts to invade it with short-sighted radical visions of urban renewal.

From Andrade there goes a thread to Bisan Abu-Eisheh’s solo exhibition Playing House (2008-11). This is a collection of found objects and remains of Palestinian houses in Jerusalem that have been torn down by the Israeli government because they do not satisfy the requirements to obtain building permits. Such permits are so expensive that it becomes an impossibility to most people. They are forced to move, but also to cover the demolition expenses themselves.

In Aydan Murtezaoğlu’s work Blackboard (2010) we encounter the construction of both written history and the history of writing at the same time. Here she uses a school blackboard to refer to a famous photograph of Atatürk who teaches the latin alphabet which he introduced in 1928 – an ambiguous, subjective and critical response which also repeats the language it critiques; due to lack of alternatives and loss of cultural memory? one might ask. Other artists meet the problem of history through diverse experiments with the quantification and spatialization of time, like Cevdet Erdek’s rulers with inscribed years. In the work carrying the striking title Ruler Coup (2009) Erdek has inscribed the years of the inauguration of the Turkish Republic, the three military coups and the year the work was made – again, a self-referential gesture which shows that history is always a carrier of subjective meanings, but also a will and possibility for subjective distortions and protest – a “coup” against the official narrative.

The aesthetics of politics reframed

The idea behind this year’s masterfully curated Istanbul Bienial is to place formal innovation at the center of the political. This comes after a canon of political biennials all over the world where form and aesthetics has often been neglected. First and foremost this biennial succeeds as an exhibition architecture, by experimentally creating a subjective space where sensation and politics are reconciled – it thus also creates an outstanding point of departure for a political future of the classical exhibition format.