May 15, 2012

Lebanon in the Armenian Imaginary:

So Close with a Distance

By Neery Melkonian

This article deals with the works of artists of Armenian descent who were born in Lebanon but left for the US or Canada at different junctures as a result of the protracted civil war.

I have been following the works of contemporary Arab artists living in the West since the early 1990s. In various capacities I have engaged with by now better known artists including Mona Hatoum, Walid Raad, Jalal Toufic, Emily Jacir, Jayce Salloum, Jamalie Hassan and Mireille Kassar largely because of our shared affinities with the country and the region’s turbulent histories.

My own mother and siblings moved to Lebanon from Syria when pan Arabism made life difficult for minorities, even though Aleppo was considered a ‘safe haven’ for the countless Armenian refugees, among them my grandmother, who had survived horrendous atrocities at the turn of the last century during the breakup of the Ottoman Empire and the ensued ethnic cleansing of Armenians from their ancestral homeland, which gave birth to modern Turkey. To this day I regard Syria as the ‘Dark Middle Ages’ of my life, to borrow a term from art history. However, I spent my early teens growing up in Lebanon, and this remains the place where I first acquired ‘speech’ – began to write, question authority, encountered my first slow dance and romance – experienced my own little ‘renaissance’! My father having lost his farm to the Syrian state lived in Doha for over a decade to earn a living for his family based in Beirut. After my sister had been invited to pursue her studies in the US by my aunt, who had arrived to Ellis Island in the 1920s as a picture bride, my parents considered southern California as the place where our family could reunite. Still, it took me ten years to ‘get over’ the rich and colorful memories of my formative years in Lebanon. When adjusting to the ‘American Way’ got rough, at times I would blame my parents for taking me away from the sweet intimacies, choosing to forget the constraints, perversions and tensions that were also part of growing up in Beirut.

This text is a very modest attempt to gather anew perhaps – after several decades of neglect or interruptions – to take stock of the dispersed practices of several modern and contemporary artists. A sort of archiving if you like, within the platform I will call, for lack of a better term, the aesthetics of a diasporic cluster.

Being offshoots of conventional Diasporas, hence without the capital D, diasporic clusters carve out a more fluid or alternate path. While maintaining certain empathies with traditional Diasporas their identification also recalls the disposition of guests, strangers, exiles, travelers, queers etc. However, as the works discussed here indicate, diasporic clusters are not satisfied with mere deconstruction, tearing, displacing or fragmenting the past either (and by extension the sheer negating of master languages/narratives, homogenizing precepts of modernism, gender positioning, father figures, nation-states etc.).

Thrice removed from the notion/ reality of their ancestral homeland and displaced by a more recent experience of war and migration, these artists translate their multiple local affinities be them linguistic, geographic, cultural etc. - which are further complicated by the reemergence of the former soviet Republic of Armenia where at best they are expats - to transform the space-less-ness of the diasporic condition into a worldly visual encounter.

To bring some light to the cracks of art-history and to the slippages of politically correct mechanisms or the blind spots of representational trends has also been a concern of mine since graduate school. They say Diasporas operate within a different timeframe, that is until a cluster becomes visible, which means that the pursuit of idea(l)s gets deferred, aborted, even fails for this or that reason. The list of higher priorities and more important subjects on the agendas of cultural elites or institutional spaces that legitimize discourse is quite long, both within and beyond the Armenian sphere, particularly with the rise of corporate or neo-liberal interests that seem to have resurrected pre-modern alliances, practices and values when it comes to art/cultural patronage. In addition, the considerable presence of Lebanese-Armenian artists within the local/regional art scene of the pre war years has almost completely disappeared in a post war Lebanon that aspires for integration. These days the “Armenian” usually becomes visible as subject or reference through the works of contemporary artists, several of whom mentioned above.

Having said all the above, what follows is by no means a comprehensive study, and while visual art is the focus and primary concern of this text, it barely scratches the surface of a rich, nuanced and complex topic. Lacking similar reflections on literature, poetry, music, theatre etc., “Lebanon in the Armenian imaginary” will remain incomplete in several respects, even though in a neighborly manner all these disciplines inform the works discussed here, including this writing itself.

Seta Manoukian

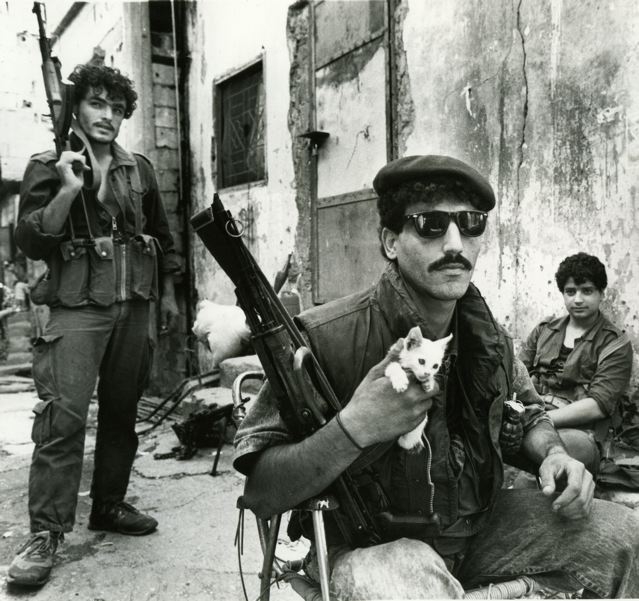

I’m sure there are others, and perhaps we won’t know better till the parallel histories of Lebanon’s international modernism in art becomes available, but I am not aware of another artist who has lived through the first decade of the Lebanese civil war, produced art books with and for children in Arab refugee camps, captured in her paintings so poignantly the fragility of a nation on the verge of going mad, participated in the 1978 “International Art Exhibition in Solidarity with Palestine” - an initiative inspired from the Salvador Allende Resistance Museum in Exile,

continued to teach art to a budding generation under increasingly intolerant circumstances, till threats on her life obliged her to leave the country she loved and often felt one with. Here, I am not referring to the remarkable practices of ‘the post civil war’ generation of Lebanese, mainly Arab, artists who have made it into the international art scene (mentioned earlier) especially since the aftermath of 9/11. I have in mind the generation who came to maturity in the 60s after the first -1958- civil war of Lebanon, and in the post cold war climate that seized the Middle East.

Through her more nuanced compositions Manoukian broke away from the appositional aesthetic paradigms prevalent at a time when either French figurative romanticism or American Cold War abstraction normalized universal depictions of victimhood or the erasure of the particular. At the same time her younger sister, Aline Manoukian, provided the world press with some of the most telling photographs of the Lebanese war.

I met Seta Manoukian in the late 1980s after she had relocated to Los Angeles, a place she gradually learned to also love but nevertheless felt less one  with for a long time. A few years later I exhibited her new series called “Balancing Imbalances” which dealt with not only her predicament as a politically engaged artist now in exile - at the time largely shunned or misunderstood by mainstream American culture - but also marked her estrangement from the dislocated culture of the Armenian community, many of whom were new arrivals from Lebanon. The latter added another layer not only to the older more ‘ethnicized’ culture of a community who had come to the US with the breakup of the Ottoman Empire, but also to the more recent influx of Armenians who escaped the political upheavals in Iran.

with for a long time. A few years later I exhibited her new series called “Balancing Imbalances” which dealt with not only her predicament as a politically engaged artist now in exile - at the time largely shunned or misunderstood by mainstream American culture - but also marked her estrangement from the dislocated culture of the Armenian community, many of whom were new arrivals from Lebanon. The latter added another layer not only to the older more ‘ethnicized’ culture of a community who had come to the US with the breakup of the Ottoman Empire, but also to the more recent influx of Armenians who escaped the political upheavals in Iran.

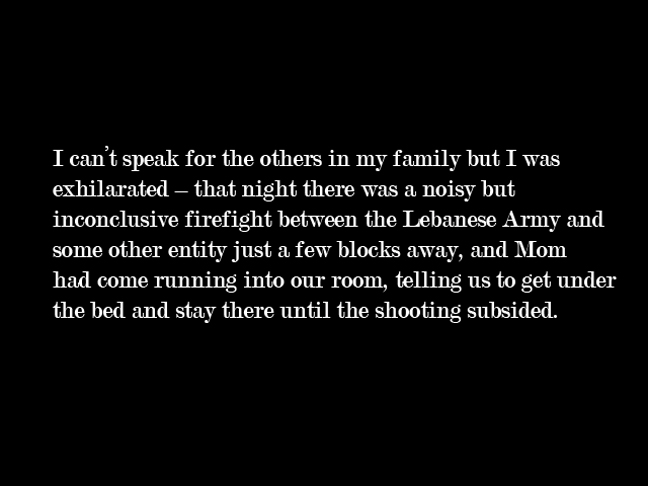

The centrality of the slippery grounds and tilted perspectives that carry enigmatic men within  Manoukian’s earlier Lebanese Civil War series (mentioned above) do not diminish her/ our empathy toward the humanity of the lone iconic female figure in this later composition which underlines a Beirut that has gone astray.

Manoukian’s earlier Lebanese Civil War series (mentioned above) do not diminish her/ our empathy toward the humanity of the lone iconic female figure in this later composition which underlines a Beirut that has gone astray.

In contrast to these, the paintings done when she is new to Los Angeles give prominence to people that form a horizontal/vertical relationship, pointing to a union destined not to meet. Instead they remain suspended in a void, together with neo-classical architectural fragments or pieces of faux furniture, expensive looking briefcases and porcelain-wares, which reinforce their un-deadness in an unsettled atmosphere of absent-presences.

Despite gaining recognition within the LA art scene, and after several years of making works influenced by her Buddhist meditation practices, Seta was eventually ordained as a Buddhist nun and says she no longer feels the need to make art.

Madeline Djerejian

The recollection of the evacuation of an expat community, and the events leading up to it on the eve of the Lebanese civil war in 1975, is the subject of a poignant single channel projection made in 2006 by New York based multi-media artist Madeline Djerejian. This twenty-two minutes long silent video entitled “The Last of Beirut” is comprised, in its entirety, of photo-text juxtapositions that attempt to reconstruct a story pieced together with the disjointed recounting of family members, friends and acquaintances who evacuated. The excerpts collected by the artist many years later re-inscribe meaning to a set of images taken by her father whose intention was to document his family’s ‘new life’ in Beirut.

All together the father took 28 photographs on the day of the evacuation which stop with their departure on a bus to the airport. As the responses she received from fellow evacuees varied in complexity and detail she noticed a contrast between what the parents and children re-member-ed. “The Last of Beirut” emphasizes this distinction by creating a filmic ‘meta-voice’ that thread disparate ‘voices’ to construct a collective story while disclosing the feeble nature of subjective recollections. To achieve this Djerejian slows down the pace between the shifting frames occasionally using details or close-ups of whole images that also remind us of the attentiveness needed at times of pending danger or threat. Only the opening and closing photos of “The Last of Beirut” give us the illusion of subtle moving images. For the rest of its duration as this incomplete story unfolds through long shots, freeze frames and jump cuts of still images (characteristics of avant-garde cinema) the viewer is absorbed by the concentration required to contemplate between acts of reading and looking, especially since the image/text pairings complement each other, only remotely.

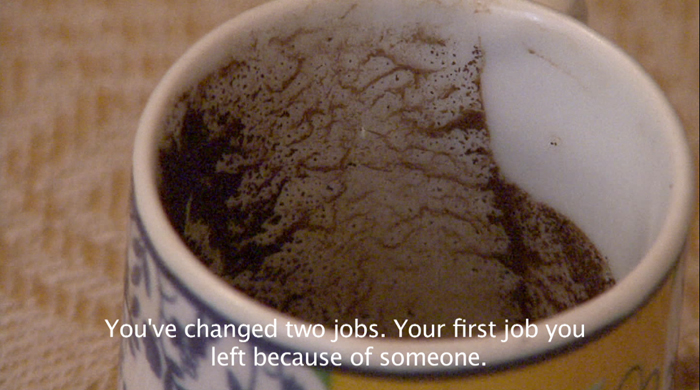

The moments that children remember include: collecting candies and comic book from the streets in the aftermath of a bomb that had recently hit the neighborhood supermarket; taking their last swim in the pool of their rooftop; crying for having to leave the dog behind; fantasizing about the adventurous nature that the evacuation might take, and watching the beautiful patterns left behind by the rockets on Beirut’s night sky. Parents on the other hand await for the smoke of the Druze bakery to signal the availability of bread for that day; avoid empty streets while driving through the city for their daily chores; wonder if the airport is open so that a child’s medicine would be delivered on time; ordering the kids who confuse the shelling with thunderstorm to hide under the bed, and packing light thinking they would be back once this ‘situation’ settles, like the ones in prior months.

The last excerpt of the video carries the ‘voice’ of a young man describing the moment he loses his naïve excitement about the idea of the evacuation when he begins to realize that the possibility of returning to the home and life he had before, as his innocence, just banished.

Hrayr Eulmessekian

Based on a selection of pre Lebanese civil war family photographs and randomly collected sounds, subsequently recorded in his San Francisco studio Hrayr Eulmessekian’s “Bruitage” is a 58 minute video shot at a painstakingly slow pace that stands as a transformative meditation on the interdiction of love, loss and mourning. As the camera zooms in and out of old black and white snapshots of unidentified rural and urban landscapes, at times further distanced by hard to hear audio, we are kept in a constant state of longing for a narrative. Despite the work’s refusal to trigger memories, its resistance to a single entry into a past and its insistence on the uncanny present, by the end we walk away with a semblance of a ‘plot’.

No sooner one begins to contemplate a possible meaning from the meager references the scene abruptly changes in “Bruitage.” An idyllic orchard dotted here and there with figures strolling recall the canvases of French Romanticism where the notions of a movement are left to the imagination of the viewer. In Bruitage however, not even a rooster’s call to rise to a new dawn affects the disquieting stillness, despite the camera’s failed desire for the contrary. This desperate attempt to bring to life recurs in a scene where the calming sounds of water that hit a sandy shore only reinforce the motionlessness of the pictured swimmers on a beach. In another scene the camera focuses on a grainy white wall then moves over a poster of horses merrily running through a pasture while chitchat, laughter and sparse sounds of musical instruments are heard in the background. Thirty some minute into the film we arrive to a block of concrete apartments with windows that look more like black holes while the whining, possibly Ottoman, music adds to an overall sense of confinement. What goes on beyond those windows remains inaccessible, like well kept secrets we are left to ponder the reach of their darkness. In another scene as the muezzin calls for prayer we almost feel the sweet sun of an afternoon resting on a number of people-less balconies while drawing attention to the grids created by their modernist architecture. This is followed by a picture of several kids sitting idly on a sidewalk of an unpaved street. And across the last image of Bruitage we can’t help but notice a crease, as if a silent lightning that signals a louder, more powerful thunderstorm on the horizon.

Can someone predict a catastrophe that has already past? Could the unrepeatable things one witnesses, or the identities that remain obscured and repressed in Bruitage be referring to a bloody civil war that has not yet happened, a violence that’s past and future at the same time? The artist seems to be telling us it is plausible. By working with a group of amateur and unrelated photographs some twenty years after he left Lebanon, Eulmessekian un-mutes their and his unbearable silence. Here, all that was once forbidden regains a native tongue, through which not only a mourning, necessary to overcome the trauma caused by the disasters of a war, becomes possible, but also; the suspension represented by a withdrawal from the tradition of artistic practice, one of the first and worst casualties of wars, becomes attainable - particularly the type that bypasses preservation ideologies along with the identity politics that ensues from them.

Greta Torossian

If Bruitage is about giving a poetic language to one’s endurance of a senseless war then Greta Torossian’s documentation of the massive post war reconstruction efforts of downtown Beirut restores humanity to the city’s inanimate architecture. The story of Beirut becoming one of the world’s largest construction sites is better recorded than what was erased in the process. A prime example of the transformation of a place overwhelmed with memory into a sedated space of neo-liberal aspirations, which have become a global phenomenon and a troubling mark of 21st century progress, and which in reality mark a regression to feudal systems.

The reconstruction of “old Beirut” along with the task of rebuilding destroyed infrastructure and creating new highways was entrusted to a private enterprise, with the country’s prime minister as a major shareholder. The state’s incapacity combined with outdated guidelines in city planning aided “Solider” to deliver its comprehensive and homogenous vision with no real civic debate on matters such as limits of densities, safeguarding historical monuments, public spaces or green parks. In order to expedite, the rightful owners of the properties were bought out, relocated or given shares in the transnational corporation that became the city’s new landlord.

With “Beirut 99: Real Vision” Greta Torossian emotively marks this unnatural absence of human involvement while also enabling the city’s ‘reincarnated souls’ to express themselves. The titles of her work speak for themselves: No Transition; Paradise; Terms of Life; Resurrection; Solitary Souls; Permit for the Future, Windows etc. Like photographs of people before and after major plastic surgery, the city’s old and new faces stand side by side (and without photoshop intervention) as if giving testimony to what they have been through and to make us ponder what destiny might hold for them.

Ironically the buildings that have undergone drastic ‘face-lifts’ look anesthetized in comparison to the old ones disfigured by numerous bullet holes and open wounds that convey the humiliation of an ousted regime. Just as man’s appetite to erase an undesirable past, tame chaos and reorganize environments, dates back centuries, Torossian’s photographs reveal the incongruous fantasies and ambivalence of producing a new reality by an emerging power. As the ruins of Roman baths pierce through one of the images we are left to wonder what Beirut’s new architecture would look like thousand years from now.

Ara Madzounian

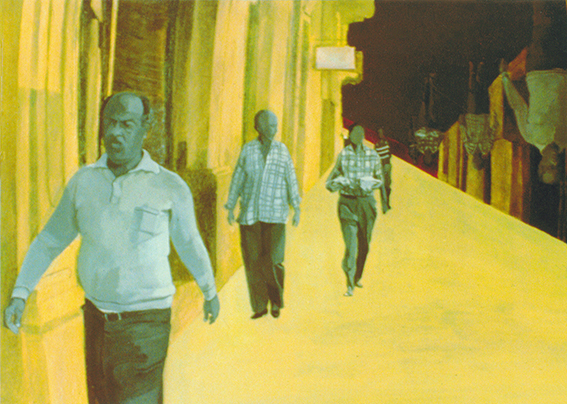

Viewing Ara Madzounian’s hundred plus photographs that document the ordinary lives of the inhabitants on the streets of Bourj Hammoud - Beirut’s Armenian enclave not far from downtown which has often been referred to as the Armenian Ghetto - one gets a radically different sense of a place. Depicted here are those who chose to stay, or did not have the means to leave. Shot by a pocket camera on strolls to reacquaint himself and process the encounter with his birthplace after being away for many years, Madzounian gives us sensitive glimpses of a community who, like Bourj Hammound itself, has endured plenty yet managed to survive the challenges of its eighty year existence.

A sense of the crowdedness, noise, smells and the hustle and bustle of Bourj Hammound comes through the collection. Like the image of intertwined electric and telephone wires that cross buildings and intersections; a highway that goes through and over a section of the neighborhood; cars parked on sidewalks of narrow streets; a storefront packed to the ceiling with washing machine parts; the knickknack vendor’s station wagon filled to the rim; alleys draped with laundry in the company of Armenia’s flag, and the basturma factory or lahmajoun and kebab kiosks that wet our appetites.

The slow-time of Bourj Hammoud also becomes evident in some of the photographs where we see people on a balcony savoring a cup of coffee and a bit of fortune telling during the midday siesta, or women and men who pause to light a candle at a stark-vaulted cemetery.

A considerable number of the photographs, however, are of elderly people patiently laboring as shoemakers, seamstresses or small shop keepers, as if oblivious or accustomed to the deteriorating conditions of their confined workplaces. Others break the routine of tending their street level stores with a game of backgammon or playing cards while a neighbor or a passerby stops to enjoy, maybe even try his luck by placing a bet. You can’t help but admire the artful life of the lean bird keeper in shorts and slippers sitting under the tin porch of his concrete rooftop, surrounded by a variety of cages and other bare essentials of his craft. Madzounian captures him at dawn and dusk dutifully flying his mates deep into the changing blue skies of Beirut, where they hover over the new high-rises that dwarf the old city and after their daily exercise and sense of autonomy is reassured they return for nourishment and to the habitual care of their keeper.

For those who are closely familiar with the history of this densely populated two-square mile suburb in northeast Beirut - like Madzounian who has returned to spend time with his terminally ill brother, himself once an amateur photographer who had given the artist his first camera and mentored him – these images also carry residues of different pasts, albeit intuitively.

Seeping through the walls, grounds and atmosphere of Bourj Hammound are the ghosts of its former identities: the swamp turned into a refugee camp while Lebanon was still part of the French Mandate; the slum that was transformed into the nucleus of, at times precariously dogmatic, nationalist revival of the Armenian Diaspora; the late 1950s Cold War site for inter-communal rivalry and violence; the internal displacement; heavy destruction and migration of thousands throughout the early civil war years in spite of the security provided by its own armed forces that created a relative safe haven, and the 1980s emergence of a sporadic underground movement for the liberation of the historical homeland.

In the last several years the survival mechanism that has managed to preserve the desired purity and insularity of this linguistic oasis is being challenged once again. This time with globalization as well as environmental degradation, as trendy shopping malls begin to alter the singular identity of this place and the unregulated dumping of toxins threatens its physical wellness, while migrant workers from Sri Lanka, Philippines and Kurds from Syria also consider Bourj Hammoud as their home away from home.

Given the above, the unsung heroes of Madzounian’s photographs prompt us to question: where are the new visions for Bourj Hammoud in a post civil war Lebanon as competing geopolitical interests are redefining it, and; whether the principles adopted over a century ago that perceived not only Bourj Hammoud but the Armenian Diaspora as a provisional space, till a return to ancestral homeland is made possible, have been reconsidered.

These photographs then invite a re-imagining that is different from the one put forth by a recent CNN clip which gives us an upbeat tour of a reconstructed block in Bourj Hammoud and introduces it as “Little Armenia” with its new generic boutiques, restaurants, an art gallery, a church, a bookstore etc. What’s disconcerting about the CNN clip is not its promotion of change but that the changes cited seem to be merely exterior.

Garine Torossian

“Noise of Time” a film by Garine Torossian perhaps best reveals how the above mentioned changes are not equal to altering Bourj Hammoud’s subterranean composition, with structural roots that date back to the Ottoman millett system including political parties, educational institutions etc. and where the dreams, hopes and aspirations of a new generation are abandoned, if not betrayed.

Torossian is known for her experimental films that deal with a search for clues about where she comes from often entangling us within a very subjective inner world. With this film, however, she is more like the camera behind the camera where she re-discovers herself, her art and the inhabitants of her birthplace which she left as a child when her family moved to Canada.

Part documentary and part fiction, the neighborhood and its streets named after the old country, becomes the artist’s source material as a cluster of characters from diverse backgrounds, some of whom act in the film, guide the narrative to tell the story of the place through their own lens. For instance the historian, whose face we never see because he is busy making amazing observations and commentaries through old maps of Beirut that he collects and has a passion for. Another character, an unemployed 40-something man who has resigned about the possibility of finding work and has a lot of time on his hands, laments the fact that he is not eligible financially or no woman will consider marrying him. Similarly, as the camera takes us through the streets and homes of Bourj Hammoud we get acquainted with the ordinary life of a 20-something woman also impacted by the war. Having lost another job recently Garine (the character who Garine filmmaker identifies with) is consumed by looking for love. During one of their outings, we see the character carefully listening to and naively seeking the advice of her customary coffee cup reader who plays the role of a therapist by telling her to ground herself in reality.

Trough Torossian’s richly layered cinematic technique that reveals a poetic of difference, what we see in the microcosm of Bourj Hammoud is how everyone and every story are connected. Not unlike the layout of the town itself which is a complex web of structures that connect with passageways and alleys that serpent through the place like a maze, or a work of embroidery - an art form still common among the older women in the community. With its fairytale quality, a signature style of Torossian, the film captures the melding of the old world with the modern exposing the contrasts between the generic shopping district Rue Arax and the poorer supposedly temporary slum areas. One of the features that stands out is how older economies of, say, artisans still form points of resistance to globalization and act as conveyers of cultural memory that are threatened to disappear.

Conclusion:

The notion of ‘a return’ forms a unifying thread of the artistic practices discussed above. Yet these returns are not to an originary homeland typical of classical definitions of Diasporas. Their returns to a more recent and actual place impacted by war are interested in states of being rather than the States that curtail the present. Their works forge a discursive space and invite critical inquiry to better understand the messiness of contemporary experience, without repeating a past trauma or an event. Their practices embrace the everyday by observing, strolling, conversing, questioning, remembering, experimenting, collaborating etc.

Since diasporic clusters meet and drift apart, depending on the frequency or intensity of the platforms that bring them together, they belong by not belonging to exhausted norms that have ceased to correspond to new realities. Energy, elements of surprise and chance encounters gravitate diasporic clusters. Their worldliness consider the transnational, international or national, without the ‘ists or isms’ associated with them. Despite the unstable or meager art economies they inhabit their works remain committed. And although provisional their activities root beyond horizontal/vertical time and space configurations.

The post script of the 1996 edition of a poem called the “Topography for a City being Destroyed” by Paris based author from Lebanon, Krikor Beledian, shares with us in Armenian his notes made within the margins of the original, 1976, manuscript. The first line of which poses the following question: “This writing was written but how, confronting what risks?”

Among the risks taken by the artists discussed above is in their resistance of apathy which in turn position them as a diasporic cluster - separated yet joint, close with a distance. At once local and polycentric. In some ways they are the 21st century heir of visionaries like Naregatsi, the medieval Armenian poet known for his book of lamentations, or Gregory the Illuminator who invented/designed the alphabet, a visual -script for what’s become a threatened language.

I end this article with a translated rephrasing of the rest of Beledian’s self-marginalized notes which registers yet another cluster of disaporic aesthetics.

“How to speak the event is an un-measurable, illicit, act, which brings me face to face with the unnamed and infinite stranger. To expose language to violence, with its probable risks, present the necessity to challenge poetry’s security and comfort. It’s not possible to be one with the event, to have it, control and inhabit it. As the exile of the event is the event, that which is to become and is not yet no/thing. We must always examine, terrorize the language, ‘to violate’ its grammar and ritual, to break down the logic of its unity. This is perhaps why a language appears foreign, an anti-language in a functioning language. What is the state of a disunited, migrating, wondering and dispersed word? Superficial writing, fragmented.” (1976)

Art historian by education Neery Melkonian is an independent researcher, lecturer and writer based in NYC. She is the founding external director and co-curator of Blind Dates: New Encounters from the Edges of a former Empire (ongoing) and Accented Feminism: Armenian Women and Art from Representation to Self-Representation (in progress).

Further reading:

Ohannes Geukjian, The Policy of Positive Neutrality of the Armenian Political Parties in Lebanon during the Civil War, 1975–90: A Critical Analysis, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 43, No. 1, 65 – 73, January 2007

Ara Sanjian, Limits of Conflict and Consensus among Lebanese-Armenian Political Factions in the Early 21st Century. Paper presented at the International Conference on the Armenian Diaspora, Boston University, February 13-14, 2010

Nizan Shaked, Something out of Nothing: Marcia Tucker, Jeffrey Deitch and the De-regulation of the Contemporary-Museum Model, in Art&Education

Khachig Tölölyan, Elites and Institutions in the Armenian Transnation, Paper given to the conference on Transnational Migration: Comparative Perspectives. Princeton University, 30 June-1 July 2001. This paper has been published in Diaspora (Vol 9, No.1). Further details can be found on the Diaspora journal website www.utpjournals.com/diaspora

and Cultural Narrative and the Motivation of the Terrorist, Journal of Strategic Studies, Volume 10, Issue 4, 12, 1987, pp 217-233

Art related:

Walid Raad, Miraculous Beginnings http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/walid-raad-miraculous-beginnings/

Jalal Toufic, The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster. Forthcoming Books, 2009. http://www.jalaltoufic.com/downloads.htm

On the International Art Exhibition in Solidarity with Palestine, Beirut Arab University, 1978 see http://www.cda-projects.com/projects-grant.asp

On contemporary Lebanese artists referencing Armenian themes see Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige Lebanese Rocket Society which question images, archives and the particular history of the region - focusing on the period of the 1960's at the time of the "great Arab dream".

Other:

Mona Fawaz and Isabelle Peillen, On Lebanon’s Slums, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and AUB Department of Architecture http://www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu-projects/Global_Report/cities/beirut.htm

Aline-Sophia HirselandTimes are Changing in Bourj Hammoud, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Local-News/Mar/14/Times-are-changing-in-Bourj-Hammoud.ashx#axzz1tvPOdJGQ