The Politics of 'Just Painting':

Engagement and Encounter in the Art of the East Kimberley

By Henry F. Skerritt

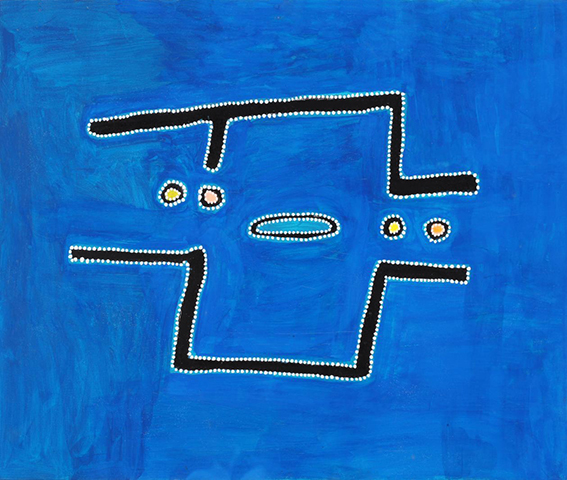

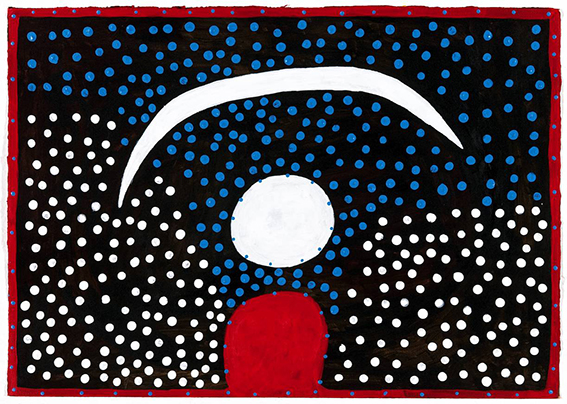

For several years, the artist Paddy Bedford had painted this site. It was a place of deep significance to his Gija people,[1] for it was here, during the ngarranggarni (creation time), that the ancestral Emu had separated day from night. But this landscape also bore the terrible weight of colonial history. Around 1924, its ridges had witnessed the murder of a large group of Bedford’s kinsmen, poisoned by station owners in retaliation for spearing cattle. In paintings like Emu 1999 [Art Gallery of New South Wales], the artist had tried to focus on the creation story associated with this place. But the darkness could only be held at bay for so long; to paint the Emu Dreaming site was necessarily to invoke these subsequent layers which combined to create the indelible meaning of this place. Thus, in 2000, Bedford and fellow Gija elder Timmy Timms resolved that it was time to resurrect the memory of this massacre, bringing it into stark, disquieting view in the exhibition Blood on the Spinifex at the Ian Potter Museum of Art at Melbourne University.[2]

The men called these stories “hard stories.” Their revelation was not a matter of political calculation, but practical necessity. Despite this, Blood on the Spinifex raised the ire of conservative historians Keith Windschuttle and Rod Moran who disputed the veracity of the Gija artists’ claims.[3] Beyond questions of truthfulness, however, the divide between these historians and the Gija artists was a cavernous gulf between two radically different conceptions of history. For Windschuttle and Moran, history was disconnected from the present, finished and done with, detached from the contemporary world. For the Gija, it was a continually unfolding process, requiring a constitutive act of remembering designed to make the past present. The resonance of the paintings in Blood on the Spinifex derived not merely from the horror of the stories or the power of their retelling but from the fact that these were history paintings that challenged the very nature of history, or at least the ephemeral nature of Eurocentric history set against the much longer forces of nature, time and being. In this conception, history is never resolved or complete, but constantly replayed and extended.

From its very beginning, Aboriginal art has had a political dimension. Forged in colonial subjugation, it is a potent and visible expression of identity and the will to self-determination. From the earliest bark paintings through to monumental works of acrylic on canvas, Aboriginal paintings are like stunning title deeds to ancestral lands. However, Édouard Glissant has noted, born from the long and painful quest to assert identity in “opposition to the processes of identification or annihilation triggered by these invaders,” the colonized identity is limited from the beginning by having to assume subject position made available only by the oppressor.[4] As a result, Indigenous art is often characterised in polar terms of resistance or submission to the dominant colonial power. And yet, the best Indigenous art has always transcended these narrow paradigms.

In part, this is due to the same temporal understanding of space that forced Bedford and Timms to recognise the colonial incursion in their paintings. For Gija, the landscape is mnemonic of both ancestral and historical events: a palimpsest in which each site registers the successive strata of memory, recording both its ancestral origins and the imprints of colonial incursion.[5] If, as Michael Dolk has suggested, “the relation between place and event is open to continual transformation,” there arises in turn a space for continual improvisation, as “each painting recreates place as a new event.[6] ”Unlike the ceremonial designs of Arnhem Land or the Central Desert, which are tightly restricted by religious law, gender and seniority, by the mid-1980s, when East Kimberley painting emerged, the space between law and painting had been largely safely negotiated. In 1993, the artist Janangoo Butcher Cherel would even declare that his paintings were about “life, not about law which is separate.”[7] According to Dolk, “By avoiding restricted designs, painting creates a space freed from symbolic restrictions of law . . . Technically a law-abiding form of ‘law-avoidance’ (beyond the reach of law), painting opens onto a realm of flux and indeterminacy, premised on exchange with outsiders.”[8]

By the time that Gija artists started painting for the market in the mid-1980s, they had over 100 years experience negotiating the boundaries of cross-cultural exchange. The pastoral frontier created an interzone that required creative forms of social performance in order to make the realities of the new order psychically cogent. Art was merely the latest incarnation of this cultural negotiation. In occupying this space of indeterminacy premised on exchange, it embodies what Glissant terms the “poetics of relation:” a realm premised on the recognition of infinite difference, but where diversity and coevality of difference in time and space is safeguarded by the opacity of the imaginary:

Every expression of the humanities opens onto the fluctuating complexity of the world. Here poetic thought safeguards the particular, since only the totality of truly secure particulars guarantees the energy of Diversity. But in every instance this particular sets about Relation in a completely intransitive manner, relating all that is, with the finally realized totality of all possible particulars.[9]

This is why Australian Indigenous art is so compellingly contemporary: it is able to be “pictured within the colonial, and at the same time, to picture the post-colonial;”[10] to express the coevality of difference, while maintaining its own identity; to recognise the existence of difference within a totality of relations that does not necessitate the fragmentation or erosion of one’s own identity; and in doing so, to reveal the connective fibres of relation that make the contemporary world comprehensible. This does not mean simply illustrating the presence of difference, but rather, revealing the very necessity of its coexistence.[11]

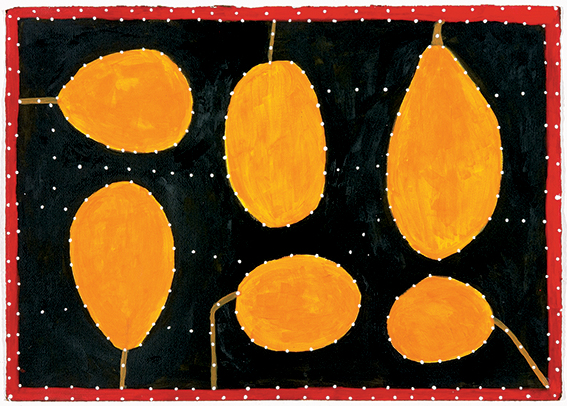

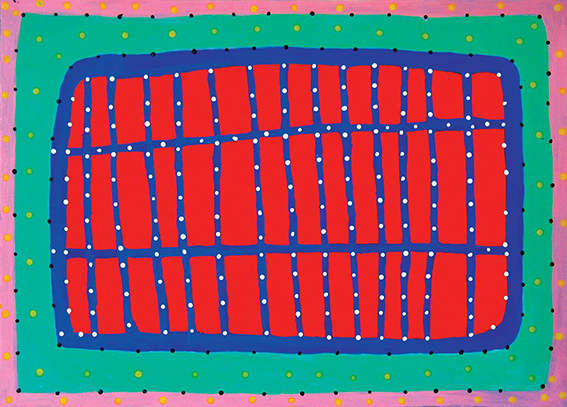

This space has opened Gija painting to an almost unlimited potential, allowing an extraordinary expansion in the field of what could constitute “Aboriginal art.” When asked to describe the meaning of one of his paintings, the senior Andinyin/Gija artist Ngarra replied, “I’m just fucking around to see what the idea looked like.”[12] Ngarra, Bedford and Cherel all concluded their careers painting with brightly coloured synthetic paints on paper. In their final years, these artists produced works that departed not only from the conventions of Gija art, but also from all of the formal characteristics that had come to be associated with “Aboriginal Art.” Recognizable totemic forms disappeared, the use of dotting became limited, and all three artists moved to high-keyed colouration. Bedford even made the provocative declaration that he had painted all of his mother’s country and all of his father’s country and now was “just painting.”[13]

Rather than seeing Bedford’s statement as a retreat into pure aesthetics, perhaps one might instead see it as divesting the dialogic burden of “Aboriginality” in favour of a border aesthetic based on cultural negotiation. Giving up the security of a unified identity can be a daunting prospect; as Bhabha notes, the fragile border between coherence and disintegration is a space marked by deep anxiety.[14] However, as Ulf Hannerz notes, the border is also a lively, lucid space, where there is scope for a renewed agency and performativity in the handling of culture.[15] This might explain the curious push-and-pull between tradition and innovation in these artists’ work, spectacularly illustrated in the paintings of Rammey Ramsey, which have swung wildly in style from neo-traditional to neo-expressionist before settling into a stately in-between space.

It is no surprise that the most adventurous explorers of these boundaries have also been the most senior artists – those most comfortable in their understanding of both the spiritual and material realms. According to Glissant, “culture today is the knowledge of the world. It’s recognising one’s own place and the place of one’s community in the world, recognizing the differences of others from oneself, and that these differences do not constitute borders.”[16] Here in the open space of the borderzone, free from the limiting paradigms of primitivism or authenticity, these works can finally speak authoritatively. As senior artists of the highest standing, Bedford, Cherel, Ngarra and Ramsey offer the landscape as a performative site of connectivity: a version of world picturing based on our shared contemporary experience of cross-cultural negotiation. At the same time, this is presented from within a defiantly Indigenous cosmology. In their paintings, both the landscape and the canvas are reimagined as sites for the successive accumulation of meaning, memory and place; conjured into being as the meeting place for our cultural communion. They show us what it means to be contemporary, and how to comprehend a world of accelerating multiplicity.

Henry Skerritt is an art historian, curator and songwriter hailing from Perth in Western Australia. He is currently undertaking PhD studies in the History of Art and Architecture Department at the University of Pittsburgh. From 2004 to 2009 he was manager of Mossenson Galleries in Melbourne, and in 2011 he curated the exhibition Experimental Gentlemen at the Ian Potter Museum of Art at University of Melbourne. He has written extensively on Aboriginal art and culture, and his writings have appeared in numerous publications, including Artlink, Art Guide Australia, Art Monthly and Meanjin.

---

1. “For Aboriginal people there is a common belief that people came from the land on which they live, and that they have occupied that land since the creation era known as the Dreaming. It is believed that during this time, spirit beings roamed across the land performing certain actions that modified or created natural features, made waterholes, springs and rivers, and filled the whole land with a spirituality that remains vitally potent to this day.

There is no, one Dreaming that is accepted by all Aboriginal people as the ‘creation story'. This concept is recognised by different names in different areas. The local Gija people refer to the concept as ‘Ngarranggarni'.

In the Ngarranggarni, Spirit Beings roamed across the land modifying or creating natural features: waterholes, springs, hills, rocks and rivers. These Beings, who are able to change between human forms, spirits, animals, plants and rocks, filled the land with a spirituality that remains vitally potent. Whilst the Ngarranggarni provides a framework for Gija people to explain and relate to times long ago or to the time of their grandparents, it also provides an important link to the present. Gija people do not think of the Ngarranggarni in the past tense, it is something that is, was, and will continue to be into the future.” Quote from the webpage of Warmun Art, Turkey Creek via Kununurra, Western Australia: http://www.warmunart.com/gija.htm

2. Curated by Tony Oliver, Blood on the Spinifex was held at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne from 14 December 2002 to 16 March 2003 and featured works by Goody Barrett, Paddy Bedford, Rameeka Nocketa, Lena Nyadbi, Peggy Patrick, Rusty Peters, Desma Sampi, Freddie Timms, Timmy Timms, and Phyllis Thomas. See Bala Starr (ed.), Blood on the Spinifex, exhib. cat. (Parkville: Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, 2002).

3. See Cathie Clement, “Mistake Creek,” in Robert Manne (ed.), Whitewash: On Keith Windschuttle’s Fabrication of Aboriginal History (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2003), 199-213, Peggy Patrick, “Statement of Peggy Patrick,” in Manne, Whitewash, 215-16, and Rod Moran, “Was there a Massacre at Bedford Downs?” Quadrant, 46:11 (November 2002), 48-51.

4. Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 17.

5. Wally Caruana, East Kimberley Painting Revisited, exhib. cat. (Sydney: Michael Reid at Elizabeth Bay, 2010), and Michael Dolk, “Are We Strangers in This Place?” in Russell Storer, Paddy Bedford, exhib. cat. (Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), 23.

6. Dolk, “Are We Strangers in This Place?” 40.

7. Judith Ryan, “Images of Dislocation,” in in Judith Ryan (ed.), Images of Power: Aboriginal Art of the Kimberley, exhib. cat. (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1993), 69.

8. Dolk, “Are We Strangers in This Place?” 25.

9. Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 32.

10. Terry Smith, Transformations in Australian Art: The Twentieth Century: Modernism and Aboriginality (Sydney: Craftsman House, 2002): 148.

11. Terry Smith, What is Contemporary Art? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009): 139.

12. Ngarra, artist statement for Mallewa, Minjuwarra and Whitefella Billycans: New Idea for a Painting, 2008 (synthetic polymer paint on paper, 35 x 50 cm). Courtesy Kevin Shaw and Mossenson Galleries, Perth, Western Australia.

13. Tony Oliver, “Preface,” in Storer, Paddy Bedford, 9.

14. Homi Bhabha, “Anxious Nations, Nervous States,” in Joan Copjec, (ed.), Supposing the Subject (London: Verso, 1994): 207.

15. Ulf Hannerz, “Flows, Boundaries and Hybrids: Keywords in Transnational Anthropology,” 1997. www.transcomm.ox.ac.uk/working%20papers/hannerz.pdf

16. Édouard Glissant and Manthia Diawara, “One World in Relation: Édouard Glissant in Conversation with Manthia Diawara,” Nka Journal of Contemporary Aftrican Art 28 (2011): 17.