June 1, 2016

Toxic Sublime and the Dilemma of the Documentary

Written by Meghan Bissonnette

For photographers interested in capturing the effects of environmental degradation, there is a fine line between documenting and aestheticizing the human impact on our planet. Over the last two decades, a group of photographers has emerged who document, through large-scale, aerial photographs, mining and oil industries, waste, pollution, and the aftermath of nuclear and environmental disasters. Their works have been labeled sublime, surreal, and even beautiful.[1] Many of these photographers aim to raise awareness of environmental issues, but the unease and ambivalence surrounding this work calls its potential to effect change into question.

Edward Burtynsky, J. Henry Fair, and David Maisel are not the only photographers working in this genre, but they are three of the more prominent.[2] Burtynsky documents, in works that are ambitious in both size and scope, industrial sites, desecrated landscapes, and the consumption that drives environmental degradation. His recent project on oil took him to several continents to capture everything from extraction and refinement, to car manufacturing, American suburbs, and shipbreaking yards in Bangladesh.[3] Fair also documents impacted landscapes; series often focus on specific industries and sites, such as coal mining in Appalachia. With both photographers, accompanying descriptive texts are necessary to understand the significance of individual photographs.[4]

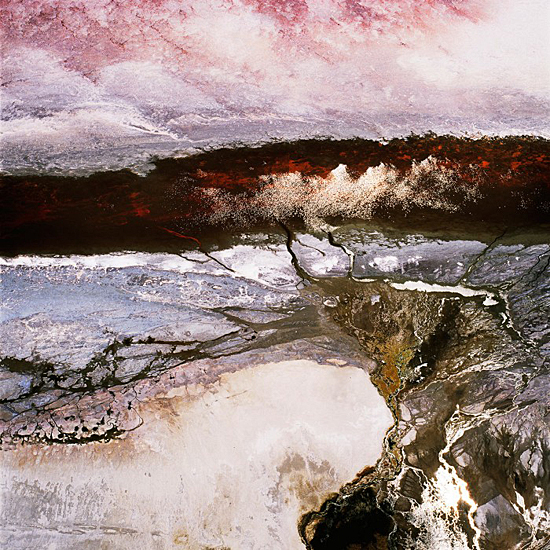

Maisel captures the abstracted and formal patterns in sites shaped by detritus, ruin and neglect. The Lake Project series, for example, documents a dry lake in the middle of California, which has caused pollution due to winds and the high levels of cadmium, chromium and arsenic at the site. However, these facts are obscured by the hauntingly beautiful patterns, textures, and gradations of blues, greys, reds, and violets, which conjure associations with Abstract Expressionist painting.

Both Burtynsky and Fair use beauty deliberately to spark the viewer’s interest, in order to create a dialogue. Fair has stated: “My goal is to produce beautiful images that stimulate an aesthetic response, and therefore a curiosity in the viewer about the causes and, hopefully, their personal involvement.”[5] Likewise, Burtynsky explains, “You don’t want to develop a dialogue by saying to somebody ‘That is very ugly.’ In a way that doesn’t open a dialogue. It actually closes it.”[6] Maisel’s work functions in a similar manner, although he hasn’t explicitly stated so. All three take photographs that function as works of art by emphasizing aesthetically pleasing and arresting arrangements of formal and visual elements.

Why are we so fascinated by the beauty created by the destruction of the landscape? Within architecture, the tradition of ruin lust helps to explain the fascination with architectural ruins. But no such tradition exists for images of the ruined landscape. Ruin lust, or the pleasure taken in images of ruins, dates to the eighteenth century with Piranesi’s prints of Roman ruins.[7] Ruin lust reached its apogee in the nineteenth century with Romanticism; for example, J.M.W. Turner and John Constable’s paintings of Roman and medieval ruins scattered around the English countryside. These ruins, overtaken by moss, ivy, and other natural elements, provided artistic inspiration for contemplating the passage of time, death, and decay. Ruin lust continues to shape recent images of industrial ruins, such as Camilo José Vergara’s studies of the decline of American urban environments and the fascination with the so-called “ruin porn” of Andrew Moore, Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre. Even the proliferation of post-apocalyptic films can be attributed to the continued influence of ruin lust.

Ruin lust helps to explain the appeal of images by Burtynsky, Maisel and Fair, but it also helps to explain the dilemma with this genre of photography. Historically, ruin lust provided a means to contemplate the transience of human endeavors, death and decay, and the fall of empires. Contemporary ruin lust—whether it is images of Detroit by Vergara, Moore, and others; post-apocalyptic films; or photographs by Burtynsky, Maisel and Fair—provides an aestheticized and detached view of destruction. Burtynsky’s manufactured landscapes, Fair’s surreal view of coal ash, and Maisel’s dried depleted lakes are hauntingly beautiful. Despite their desire to raise awareness for environmental issues, these images evoke the detached gaze of contemporary ruin porn.

The distanced, aerial view contributes to the aesthetics of these images. Without specific details, the patterns and colors created by the flow of coal ash, or the accumulation of toxic elements, provokes comparisons to art. These images must be contextualized to be effective in instigating a dialogue. When Shipbreaking #13 is viewed in the context of Burtynsky’s oil project, the scale of our dependence on oil is evident. Likewise, understanding Maisel’s work requires information on Owen Lake. When taken out of context, and put in exhibitions or glossy coffee table books, they become beautiful images, examples of ruin lust.

Furthermore, the absence of any human element provides a detached, aestheticized view of environmental degradation. In Maisel’s photographs, there is a noticeable absence of people. Burtynsky and Fair only rarely include people, and when they do, they are tiny and insignificant. The minimal traces of human life, the lack of context, and the distanced view, result in photographs that are ambivalent, even malleable in meaning. Critics have noted that Burtynsky’s work appeals to both environmentalists and industrialists. But these works also fail to show us the perpetrators or the victims of this “slow violence.”[8] With greater attention in recent years to economic inequality and how climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels disproportionately impacts the poor, the absence of victims cannot be ignored.

Can photographers address current environmental issues without falling into the trap of ruin lust? Perhaps what is needed are images that reject the spectacular and sublime. For instance, photographs of the Detroit public school system surfaced recently on Twitter.[9] These amateur cell phone pictures revealed mold growing in classrooms, broken plumbing, and unsanitary conditions that were undoubtedly shocking. They also acknowledged the victims of economic inequality that are often erased from ruin porn. The verdict is still out regarding their impact in bringing necessary changes to Detroit’s grossly underfunded school system. But they contradict statements by Fair and Burtynsky that beauty is necessary to start a dialogue.

Alternative approaches are seen in Yao Lu and David T. Hanson’s use of documentary photography to address environmental concerns. Yao Lu combines images that recall traditional Chinese landscape painting with photographs taken of dumps and construction sites. The green tarps are used at construction sites to keep detritus from blowing away. These works speak to the industrialization of China, but they also point to what is being lost with China’s push to modernize. Like historical forms of ruin lust, his landscapes allow the viewer to contemplate the passing of time and the transience of human endeavors.

The influence of conceptual art and its use of text and data is seen in Hanson’s Waste Land series, which documents sites on the EPA National Priorities List—sites that pose a risk to health or environment. Hanson’s aerial photograph of the site is accompanied by a U.S. Geological Survey topographic map that has been modified to indicate the location, as well as the official EPA text that details the hazards of the area.[10] Now thirty years old, these works still have potential to educate audiences. However, an updated version is needed, one that examines the conditions that shape the environmental crisis today.

Works by Burtysky, Maisel and Fair are ambivalent in meaning. Critics have expressed their discomfort with Burtynsky’s works, yet his photographs, and those of Maisel and Fair, continue to enjoy popular appeal. They promote a detached, aestheticized view of environmental degradation that makes them problematic as a form of critique. With increasing attention to the impact of climate change on the poor, and on developing nations, documentary photography can play a pivotal role. Yet new models are needed. The works of Yao Lu, David T. Hanson, and anonymous amateur photographers are just three alternatives proposed here.

Meghan Bissonnette is a Lecturer of modern and contemporary art at Valdosta State University in Valdosta, Georgia. She was awarded her PhD in Art History and Visual Culture from York University in 2014 with a dissertation on David Smith. Her current research interests include 1950s metal sculpture, apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic visual culture, and the legacy of ruin lust.

[1] The term “toxic sublime” has been used on several occasions to describe Edward Burtynsky’s work, and has inspired the title for this article.

[2] All three were included in the recent book Landmark: The Fields of Landscape Photography, while Maisel and Burtynsky were included in the influential exhibition Imaging a Shattering Earth: Contemporary Photography and the Environmental Debate (Meadow Brook Art Gallery, 2005). See William A. Ewing, Landmark: The Fields of Landscape Photography (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2014).

[3] Edward Burtynsky, et. al., Burtynsky: Oil (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2009).

[4] Fair provides descriptive captions to his photographs on his website, http://www.jhenryfair.com, while both photographers include essays by scientists and environmentalists in book collections of their work. Fair's latest book, Industrial Scars: The Hidden Costs of Consumption (2016), will be published this fall by Papadakis.

[5] J. Henry Fair, “Statement,” in Landmark: The Fields of Landscape Photography by William A. Ewing (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2014), 247.

[6] John K. Grande, “Beauty Going Nowhere,” Art Papers 28:6 (Nov./Dec. 2004): 26.

[7] I’ve borrowed the term “ruin lust” from the exhibition Ruin Lust held at the Tate Britain (March 4 – May 18, 2014). A pivotal source on ruins in art and literature is Christopher Woodward, In Ruins: A Journey Through History, Art, and Literature (New York: Vintage Books, 2001).

[8] Rob Nixon uses the term “slow violence” to describe environmental destruction which is incremental and slowly unfolding, rather than sudden or spectacular. See Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2011).

[9] Dylan Hock, “Detroit’s Teachers Want You to See These Disturbing Photos of Their Toxic Schools,”U.S. Uncut, January 17, 2016, accessed May 8, 2016, http://usuncut.com/class-war/detroit-teachers-want-you-to-see-these-disturbing-photos/ More photos can be seen on Twitter: https://twitter.com/teachDetroit

[10] David T. Hanson, “Introduction,” in Waste Land: Meditations on a Ravaged Landscape (New York: Aperture, 1997), 6.