June 1, 2016

Wild plants.

Activism and autonomy in contemporary art.

Written by Christel Pedersen

In recent years a new form of practice has begun to sprout; a practice which connects to the sphere of art or to the poetic, but which at the same time employs or refers to activist strategies; which takes place in the public or semi-public sphere, addressing questions related to ecology. Contrary to the traditional, ontological understanding of art as something other than reality, that is merely an imitating, symbolic or referential way of relating to it, this new type of practice is so closely tied to reality that the difference is barely identifiable. Instead, it approaches activism, that to a far larger extent is associated with reality, and maybe even to a form of hyperrealism, through its radical presence or intervention in the sphere of reality. When its agents nevertheless keep insisting to inscribe themselves in an artistic frame of understanding, does this express a will to prioritize investigations that are purely aesthetic or internal to art, over art’s critical, reflexive content? Or rather, is it so that precisely the artistic narrative contains certain particularly subversive opportunities?

Thus, while from a strictly formal perspective it can be difficult to differentiate between art and activism, it seems all the more important to investigate which forms of space and contexts this new type of practice unfolds within. The project Banque du miel was realized by the french collective Parti Poétique, and has since 2009 expanded to encompass a steadily growing network of participants in France and several neighbouring countries. The collective, whose goal is to ”pollinate” urban environments, also calls their project an art project. It is open to everyone, but the number of accounts accessible for each honey bank is limited. When participants enrol in the project, they simultaneously open a savings account in the Honey Bank, and a bankbook is issued in their name, giving them the right to collect parts of the honey that is produced for their specific bank.

Just like serially produced artworks like lithographies and cast bronze sculptures, the bankbooks are printed in a limited, numbered edition. When opening an account, each participant deposits a minimum amount which contributes in financing the beekeeping. According to the Parti Poétique itself, the fundamental idea behind the project is to dematerialize the human-made economic capital by channelling it into a form of production that is not carried by speculation or intended to produce surplus value. With the name Honey Bank and the application of an economic teminology and world of concepts, the collective takes advantage of the reference to the established economic system, yet simultaneously tries to point out a new form of practical, natural capital as a replacement for abstract economic capital. Therefore, it is not a project which serioustly attempts to break up or reject what already exists, rather it works to unsettle and displace the attributions of value that are typical to the system. Even though its operational platform is public space, and despite the fact that it has obtained an extensive reach through its network structure, its sphere of action is also at the same time very much self-circumscribed. The purpose is not to make interventions, but to establish parallel, bubble-like rooms of action.

The Danish artist Camilla Berner works within a more site specific, local context, exploring the metaphorical potential of wild growing plants. From early spring to late autumn 2011, she was engaged daily in a transformation of the – at the time empty – construction site Krøyers Plads at Christianshavn in Copenhagen into an urban garden, Black Box Garden. The plot of land, which is one of the city’s most expensive, has remained a desolate and unused since 2004, because the original building project was rejected after a heated, public debate about its architectural qualities and integration into the environments. Camilla Berner did not bring her plants or material from outside, but instead took advantage of what she found on-site, divided the plants into sections and created a form of rhizomatic order. At the same time, she mapped the site’s diversity of species and kept a logbook over its history and specificity, and over the new field of possibilities that can suddenly appear once diverse, political and economic interests are temporarily suspended. Through her non-interventionist access, the artist reinvested in the site as autonomous, having a value in itself; precisely as an in-between. Black Box Gardenis closely related to the Austrian artist Lois Weinberger’s exploration of the border areas between natural and cultural spaces. Weinberger, one of the pionneers of ecological art, often establishes small, limited freezones for wild growing plants in public, urban contexts. In Salzburg as part of his work Burning and Walking from 1993, he broke up the asphalt into an 8 x 8 meter square, which he left to itself for an entire summer, and for Documenta X in Kassel in 1997 he planted neophytes from southern and southeastern Europe on a 100 meters long stretch of railroad, as a metaphor for contemporary migration.[1]

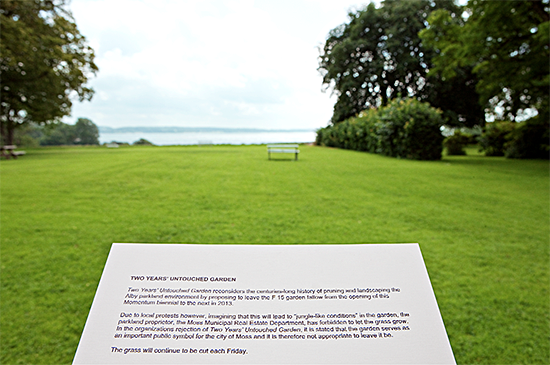

The examination of public space as a sphere of interest was also the starting point for the artist collective Wooloo’s contribution to The Momentum-Biennial in Moss, Norway in 2011. Two Years’ Untouched Garden, that the collective for their part had thought would become a ”sculptural intervention”, consisted in letting a pittoresque garden facing the Oslo-Fjord, located behind one of the biennial’s two venues, Gallery F15, remain untouched from the time of the biennial’s opening during the summer 2011, until the opening of the next exhibition two years later. The garden would be open for its normal use, however, one should not intervene in the natural surroundings; the grass and the trees should not be cut. According to the artists, this simple intervention was thought as a commentary to Norway’s double international engagement; on one side, a contributor to countries trying to reduce deforestation; on the other, as an oil exporting nation that exploits its own natural resources. At the same time, the work also had a more art internal, critical ambition, related to the exclusive nature of biennials and the global art economy.[2] The artists wanted to address the audience from an external position and create a work that did not cost anything to make. But already before the work was realized, the reactions to it had serious consequences, with regard to both form and content. Several local politicians found it inappropriate to transform a garden of local-historical importance into wilderness, and as a result, the municipalities decided to prohibit the artwork, and made an official regulation saying that the grass must be cut every Friday. Somewhat paradoxically the work, which precisely addressed non-intervention, itself became an object of local-political intervention. While the original work was never accomplished, its concept and history was instead explained on an information board that was mounted in the entrance to the garden. Hence, a discursive, conceptual work was developed, which just like Camilla Berner’s Black Box Garden revealed some of the underlying power structures and potential conflicts of interest, that are related to even apparently neutral zones in public and semi-public spaces. Both works were based on a form of non-intervention – or at least an intervention that is based on something that already exists, and which is barely changed or modified through some quite moderate approaches – and yet, with their wild growing plants and weed, they become powerful (imagined) images of protest and critical sensibility.

While Wooloo’s original project was prevented by a local-political aesthetic censorship, the municipal intervention into artistic freedom in another, specific context, is also the very starting point for the form of literary activism that the French author Nathalie Quintane represents. In her essayistic book Tomates from 2010, she republishes a recipe for a homemade nettle fertilizer that makes tomato plants grow into the sky. In France, however, it is illegal to sell or distribute recipes for organic fertilizer, which means that the publication of this recipe that the artist has herself received from her father, is an act of civil disobedience. The author takes advantage of literature as an established, legitimizing genre for orchestrating subversive actions, that address political questions with a reach that goes beyond ecology. In fact, it also connects to the polemic around the anti-capitalist manifesto L’insurrection qui vient [The coming insurrection], that was published in 2007 under the secret, collective writer-pseudonym Comité Invisible [“The Invisible Committee”]. The next year, 9 young people from the town of Tarnac were arrested during a large, nightly raid involving helicopters and dog patrols, under suspicion of conspiracy and relations with sabotage-raids against the French TGV-railway network. One of them, Julien Coupat, whom the government perceived as the group’s ideological leader and main author behind L’insurrection qui vient, was imprisoned for more than half a year. After his release, the people under charge were refused the right to assemble, a decision they declared, through a text they had written together, that they did not intend to respect. With her publication of the forbidden nettle fertilizer recipe, Quintane makes a new act of resistance with reference to the former, and thus indirectly challenges the criminalization of political-philosophical thought and the state power’s interventions in intellectual freedom.

In spite of the different methodic approaches that the mentioned works and projects demonstrate, what they have in common is their replacement of the materialized art object with a bodily and local rootedness within a specific sphere of operation. They represent what the American art theorist Hal Foster identifies as a change from qualitative – stylistically and historically determined – art internal affairs, to an «interested» art that challenges the borders of contemporary cultural thought and is occupied with discursive issues that are external to art; from ”medium-specific elaborations to debate-specific projects”.[3] These works and projects are inscribed in an artistic frame of understanding, either through the artists’ own communication about them, or through the context they take place in, and they thereby connect to a network of associations that stem from the avant-garde’s challenge to established socio-cultural and economic values. The unpredictability in the act of cultivating weed on empty plots can be reminiscent of the dadaists’ anarchistic worshipping of the fortuitous or of Fluxus art’s temporally extended, processual works and formal arbitrariness, that escape art’s traditional genres. Just like in intermedia art, focus is not directed at producing works with a finite and determined form, but rather at transitoriness and at the discursive communication or exchange; and hence at dissolving the borders between art and reality. On one hand, with its immaterial, interventionist form, eco-activist art could, in principle, be inscribed into several frames of understanding, but paradoxically, it thereby simultaneously establishes a connection to avant-garde anti-art-strategies, and hence also to art-historical discourse.

In the article ”Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces” the Belgian philosopher Chantal Mouffe argues that capitalism, with its conquering and neutralization of some of the archetypal counter-cultural strategies such as self-organization, search for authenticity and rejection of hierarchies, has expelled counter-culture from its own domain and necessitated a search for new aesthetic strategies for orchestrating resistance.[4] According to Mouffe, this search culminates in a new form of artistic activism, characterized by an agonistic approach. This activism challenges, within a public context, the current hegemonies, and aims to reveal disagreements and conflicting interests without seeking to reconcile them.[5] Several of the works described earlier relate, precisely, to the hegemonic discourse they are a part of, and seek to challenge its premises. Their success seems to be at its greatest, from an activist, subversive perspective, when they manage to establish a difference or ambivalence in relation to their point of departure.

Christel Pedersen is an art-historian, writer, lecturer, and curator, working as managing director of the Gallery of Danish Furniture Art in Paris, France, since 2010. Christel Pedersen holds the DEA-degree from Université Paris VIII and the Magister-degree from the University of Copenhagen.

[1] Neophytes = invasive alien species. According to wikipedia.no, ”An invasive alien species is a species appearing outside of its natural habitat and potential distribution. The normal understanding of the term is that the species was transported to a new place by human beings. Some invasive alien species represent a threat to the site-specific nature and economy.”

[2] See Jacquelyn Davis (2011)

[3] Foster (1996), p. xi

[4] Mouffe (2007), p. 3

[5] Mouffe (2007), p. 4

Bibliography

Jacquelyn Davis (2011), “Wooloo at the Sixth Momentum Biennial: Moss, Norway”, http://www.artwrit.com/article/wooloo-at-the-sixth-momentum-biennial/

Hal Foster (1996), Return of the Real, The MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, London, England

Chantal Mouffe (2007), « Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces », in Art & Research, A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods, vol. 1, no. 2, summer 2007

Nathalie Quintane (2010), Tomates, P.O.L, Paris