June 1, 2016

Will Wilson and Jetsonorama: Confronting Resource Extraction in the Navajo Nation

Written by Michaela Rife

Two men stare into the photographer’s lens, locking eyes with the viewer. They stand back to back, both turning their faces toward us in three quarter profile. Both wear white collared shirts, with beaded necklaces visible around their necks. Both men have a caked yellow substance dripping down their faces, past their bloodshot eyes. The ominous presence of gas masks emphasizes the apparently toxic nature of the environment. The sky behind the men is heavy with dark clouds, obscuring distant mountains and casting a grey light on the low-lying water behind them. The water, or liquid if it is not water, lies still, nearly covering a ground that includes fence posts, implying that this was not a space intending for flooding, small tufts of shrubbery and patches of dirt disrupt its surface. (fig. 1) This image is one of Diné artist Will Wilson’s Auto Immune Response (AIR) series, ten archival pigment prints that have been digitally constructed by Wilson, who places his figures (the artist himself, sometimes doubled or tripled) in a composite setting. Begun in 2005, Wilson describes the series’ subject as “the quixotic relationship between a post-apocalyptic Diné (Navajo) man and the devastatingly beautiful, but toxic environment he inhabits.”[1] To confront Wilson’s work is to contend with the phrase “toxic environment” and to attempt to offer some definitions and histories for both words in this context.

We can take environment to encompass not only the politically designated area of the Navajo Nation, but also the much larger Navajo Homeland, Dinétah. Toxic, to a large degree, refers to the history of colonial resource extraction in this area. The story of resource extraction in Dinétah is one of both sudden devastation, like the 1979 explosion of a dam near Church Rock, New Mexico that sent uranium mining waste coursing through the water system, more devastating but far less known than Three Mile Island. It is a story of devastation that fits into Rob Nixon’s now oft-invoked theorization of “slow violence,” the kind of devastation that sees Navajo miners working in the uranium mines without any protective equipment and living in houses constructed from contaminated material. The kind of devastation that sees cancer rates sore amongst those that live in the area where radioactive dust blows on the wind.[2] This essay will examine some of the histories that have led to this violence and devastation but, taking a lead from Wilson’s invocation of “response” in his series title, it will focus on artistic projects (both his own and those of Navajo Nation-based artist Jetsonorama) that work to reclaim agency by visualizing, reacting and responding, despite seemingly insurmountable contamination.

First it is useful to explain both terms and history. Diné literally means “the people” in the Navajo language, and is a term of self-identification. The term “Navajo” comes from an early Spanish colonial attribution. I will use both terms, in keeping with the cited source. It is also important to emphasize that the “Navajo Nation” refers to the legal boundaries of the U.S. Government defined reservation, a region that has expanded and contracted with treaties and legislation. Today the borders of the Navajo Nation lie in the Four Corners area of the United States, though the land area is smaller than Dinétah, which includes portions of what is now defined as southern Colorado.[3] Diné land includes protected sites, including cinematic synecdoche of the imagined Old West, Monument Valley.[4] The Grand Canyon lies within Dinétah. Further, it is important to note that this is not simply a story of exploitation, rather it is a story of exploitation that has been facilitated by Western land values, which have held that one area can be preserved while another is used. To be clear, this is not to imply that preservation cannot also be a form of exploitation. Rebecca Solnit has written of the violence that accompanied the path to “preserving” Yosemite Valley, including the forced removal of the Ahwahneechee. But as she explains, the histories that insist on seeing them as “extinct” so that a now unpeopled landscape can be preserved as wild, rely on a notions of culture as blood quantums, as in the story of Toruya (Maria Lebrado) “the last full-blooded Ahwahneechee,” who died in 1931.[5] In this binary understanding you are either “pure and preserved” or “contaminated and extinct.” Kim Tallbear has written extensively on the implications of DNA testing for tribal enrollment purposes and notes the connection between how indigenous peoples and land have been framed for “preservation.”

A shared narrative, that of the vanishing or dying Native, has framed the response to multiple literal and figurative bodies—indigenous bodies, the land, and the indigenous body politic—by the state. Like bioscientists in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries with their imperative to bleed indigenous peoples before it was too late, a nineteenth-century Euro-American painter and early twentieth-century geologists and government agents saw the place where the red stone [Pipestone in Minnesota] lies as an artifact of a waning culture and time. They produced a “National Monument” to conserve it.[6]

As with all of Native America, some lands have been partitioned as worth preserving, in many cases at the expense of those that call these areas home, while others have been given over as environmental sacrifice zones. In large part this separation has been allowed by shifting western land values, as Tallbear notes by referencing these “painters and geologists.”

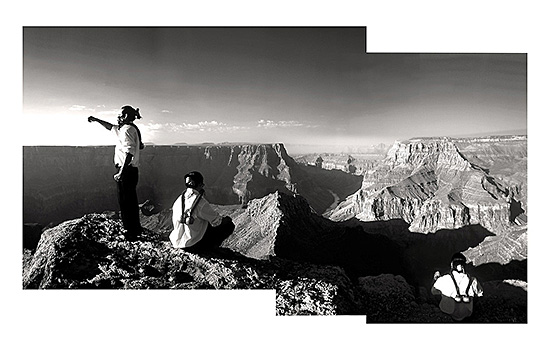

This false binary of pure and magnificent, or contaminated and expendable plays out in Wilson’s work, where some images show landscapes traditionally coded as sublime, while others show the seemingly barren landscapes that were unappreciated for most of the nineteenth century.[7] (figs. 2 and 3) Historian Martha Sandweiss has explained how early photographs of the arid Southwest “resisted easy incorporation into the national myth of manifest destiny that emphasized economic growth and political expansion. Photographs of treeless prairies and waterless deserts...had the unsettling potential to suggest that the arid West lacked the necessities of settled life.”[8] This is to say, they seemed to lack the potential for agriculture. The history of the United States government and its agents in Dinetah is one of shifting land values, from “useful” to “worthless” and back again. Wilson’s character resists arbitrary borders by existing in both, and yet his ever-present gas mask demonstrates that environmental contamination also ignores arbitrary borders.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the North American West was rapidly seized and transformed into the western United States. It was in this period that Federal Indian Policy shifted from one of pushing native peoples into uncolonized territory to one of containment on reservations, in service of the droves of settler-colonists and land spectators overrunning the West.[9] The US targeted different tribes for different reasons, for the Navajo a dominant factor was their geographic location on the route to the California gold mines.[10] In the years following the “official” ceding of Navajo land to the United States from Mexico, with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the United States went on the offensive through a slate of treaties and military actions, culminating in the tragic Long Walk, or more accurately a series of forced marches from August of 1863 to the end of 1866, out of Dinétah to the intended reservation of Bosque Redondo and Fort Sumner in present-day southeastern New Mexico. Though this component of the Federal Indian Policy sought to “civilize the Indian” on reservations, the more lucrative purpose was a land grab, for either mineral resources or agriculture.[11]

The Diné were unusual among Native groups in that, in 1868 they were allowed to return to some portion of their homeland, though to a reservation with much smaller borders. The reasons for this are complex but include Diné resistance from within Bosque Redondo.Ironically for the topic at hand, a dominant reason for this apparent concession was the fact that Western land was at a premium and the reservation portion of Dinétah seemed to hold none of its suspected mineral riches.[12] Every step of this history reinforces the idea that land can hold vastly different values. For the US government it was first valuable as a route to minerals, then as potentially mineral-rich itself, then abandoned when found to be apparently barren. For the early years of the Navajo Nation, the value assigned to it by the United States government was merely as a place to contain a Native population. Of course the value given the land by the Diné was, and is, its status as a homeland, not to mention the ability to exist with the land in good health.

The health of Dinétah arguably received its largest blow when uranium mining began in the twentieth century. Initially dependent on foreign sourced uranium ore, with the arrival of the Cold War the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission announced in 1948 that they would act as the sole purchaser, and guarantee the price for all uranium mined in the United States. This precipitated a mining boom on the Colorado Plateau and the Navajo Nation.The post-war period saw many Navajo men return from military service, looking for work and finding that Uranium mining provided an opportunity, typically the only opportunity, to work close to home. According to the important 2006 study by Brugge, Benally and Yazzie-Lewis, for many families this represented “first contact with the broader U.S. wage economy. These Navajo families were thankful at the time that they had employment.”[13] Throughout the mining boom Navajo men held positions in the mines, earning minimum wage or less, whilst their foreman and bosses were typically white.[14] Widows tell of their miner husbands washing in basins after a day’s work and the water turning yellow, a story that makes it hard to read the liquid visibly dripping from Wilson’s face in AIR 5 and 6 as anything but poisonous. The Navajo population now suffers disproportionately from autoimmune diseases, lung cancer and other health effects, not just from their years in the mines but also from the radiation that permeated daily life. Brugge et al. explain that the Navajo language has no word for radiation, and that the population “was isolated from the general flow of knowledge about radiation and its hazards by geography, language, and literacy level.”[15] This general flow of knowledge refers to the fact that by the late 1930s, there was no remaining scientific doubt surrounding uranium mining and high rates of lung cancer, and yet only in the 1950s did some federal government officials and scientists began to advocate ventilation as a preventative measure in stemming disease, and still the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) stood in the way. The government’s response was to encourage states and mine owners to improve conditions of their own volition, rather than introduce regulation.

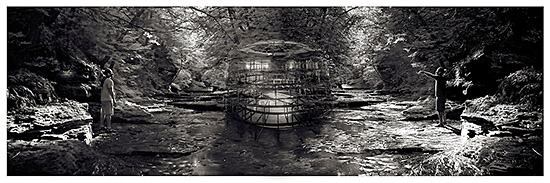

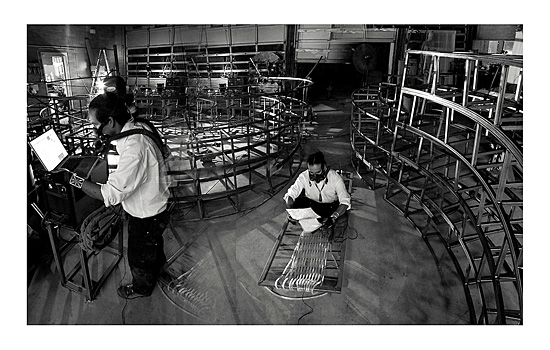

In addition to their failure to act on industry regulation, Brugge et al identify the Federal Government’s role in the tragic history of public health in the Navajo nation, where through the Second World War, government healthcare attempted to eradicate traditional sources of health knowledge, mirroring a lack of interest in native sources of land knowledge. For example, Diné cosmology says that when the Diné emerged into the fourth and present world, they were given the choice between two yellow materials, the yellow dust that came from rocks (uranium) or yellow corn pollen. In choosing the corn pollen they were warned that removing the yellow rock from the ground would bring evil.[16] For the Navajo, the value of uranium was derived from leaving it in the ground. Though it was not left in the ground, it is still to Diné cosmology that Wilson turns, to the traditional hogan. (figs. 4 and 5) Wilson explains that his character in the series turns his hogans into greenhouses, which have been installed with the photographs in later iterations at venues such as the Denver Botanic Gardens (2011) and at the Wheelwright Museum, Santa Fe (2014-2015). Both hogans, in illustration and in exhibition, serve to further the idea of response. Both facilitate the cultivation of indigenous food plants, illuminating a path of resilience and perhaps ecological healing. Wilson describes the structures as “a place to ride out the apocalypse and develop strategies for survival.”[17]

Traci Brynne Voyles, author of the recent study Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium in Navajo Country, explains that the Diné and residents of the Navajo Nation have not simply accepted the pollution of resource extraction, have not capitulated to its daunting effects. Due to the efforts of citizen activists, the Navajo Nation placed a moratorium on uranium mining in Navajo country, and yet it should be noted, contestations over boundaries remain with mining companies and though they have not fared well under the Obama administration, Voyles writes that they mass at the borders, waiting to charge.[18] Furthermore, residents of Navajo Nation must contend with mines that were never cleared and so-called zombie mines, which were decommissioned but not destroyed and are waiting to be reopened. “The notion that the uranium industry could be seen as zombie-like—as undead—provides a compelling metaphor that suggests connections to larger systems of the threat and promise of environmental and social ruin in an increasingly toxic world.”[19] Describing Wilson’s work, Jessica Horton and Janet Catherine Berlo explain that uranium, in Diné thought, is sometimes personified as a monster or snake, positing that “the character in the photographs refuses to fall victim to toxic agents. In an act better characterized as philosophical reckoning than pragmatic response, he draws upon the timeless precepts governing Dinétah to battle the awakened monster.”[20] In fact, as Wilson explains, the two figures staring into the camera in AIR 5 are “a reference to the Diné hero twins that defeated the monsters making this world habitable.”[21] If we concentrate on Wilson’s title for the series “Auto Immune Response,” and look at his character building and researching, it is easy to question this assertion of reckoning not response. I contend that it is both: a “philosophical reckoning” coupled with a refusal to accept radioactivity as insurmountable for “pragmatic responses,” like the cultivation of indigenous food plants. And yet, in learning the stark realities of uranium extraction, it becomes difficult to read these images without a feeling of futility, of fatality. Are not the materials of the Hogan poisoned as well? And as Voyles notes: “Studies have also found that uranium has genotoxic and mutagenic effects; that is, uranium poisoning can change the genetic material of a chronically exposed population, even further expanding uranium’s influence on future populations in ways that are yet unknown.”[22]

On this bleak thought it is instructive to turn to Giovanna Di Chiro’s discussion of environmental justice, a field that addresses environmental racism (the disproportionate effects of environmentally harmful practices on populations of color). De Chiro necessarily reconsiders conceptions of “environment”, noting that when the term is conflated with wilderness preservation (think National Parks) concerns of human health and wellbeing are not attended to.[23] Environmental racism works here on two main levels, where the health and well-being of a predominantly Native American population is deemed an acceptable sacrifice in the quest for nuclear power, and where an already degraded landscape is placed outside of wildland status and thus not worthy of saving, a theme that continues our discussion of dichotomous land values. As Di Chiro explains:

The discourse that opposes an Edenic or sublime nature to a fallen culture either categorizes people of colour as identical with nature, as in the case of indigenous peoples or Third World natives …or classifies them as people who are anti-nature, impure, and even toxic, as in the case of poor communities of colour living in contaminated and blighted inner cities or in the surrounding rural wastelands....Wilderness or Eden must be located where these “toxic” or “fallen” people are not.[24]

Wilson’s work forces us to ask if the places that we assume to be Eden and the ones we assume to be toxic might not be so different, and to see that neither category can be adequate. His Responses offer one way to confront the very present legacies and realities of resource extraction, Jetsonorama’s murals offer another.

Jetsonorama is the artistic moniker of Chip Thomas, a black physician who has been living and working with rural populations in the Navajo Nation for decades. His projects, including large photographs of friends and patients wheatpasted on roadside stands and murals produced through collaborations with artists and locals through his Painted Desert Project, have strategically appeared in the Western Agency of the Navajo Nation which, though rural, is highly trafficked due to its proximity to the Grand Canyon and Monument Valley, among other tourist attractions. But as demonstrated this same land is home to uranium. Lately, Jetsonorama has looked to the realities of resource extraction, from the uranium industry to the complex relationship with coal. In a case that can be read as a response to the problem Di Chiro presents, Jetsonorama depicts Lola. (figs. 6 and 7) The story is that she is a sheepdog, who has apparently been drinking from water contaminated by a uranium mine. Her radioactivity has made her something of a local legend, where other flocks have three or four sheepdogs Lola manages her own, and coyotes purportedly do not attempt to steal from hers. Jetsonorama transforms this narrative of contamination from the rhetoric of zombie to one of superhero, where Lola is the Super Atomic sheepdog.[25] In another potential response to Di Chiro’s dichotomy, theorist Karen Barad, writing on the labeling of monstrosity, notes that it “cuts both ways. It can serve to demonize, dehumanize, and demoralize. It can also be a source of political agency. It can empower and radicalize.”[26] Jetsonorama presents a creature that falls into the later categories, Lola’s contamination is empowering, not in the way that it excuses or forgives environmental contamination, but in the way that she refuses to be demonized or denaturalized.

Uranium mining and the lack of clean-up is a relatively clear case study of environmental racism. But it is important to note that while uranium extraction has been banned, we hope for good, resource extraction remains a massive, often toxic industry. Voyles writes that the United States has disproportionately relied on resources, like coal and oil pulled from indigenous lands, while “Native people often benefit the least in terms of economic and cheap energy.”[27] The story of the Black Mesa coal mine, yet another case study in environmental injustice, demonstrates the complexities of resource extraction within the Navajo Nation, where the mine became a symbol of Native exploitation and served solely to power the metropolises of the Southwest and Southern California. But while the 2006 shutdown of the Black Mesa mine (located in the Hopi and Navajo Joint Use Area) was an environmental victory, it cost the Navajo 15 percent of their tribal revenue and the Hopi 33 percent, and it was devastating for local employment.[28] But, as Jetsonorama’s work makes visible, extraction continues across the Navajo Nation. In an eerie series commissioned by the environmental organization 350.org, Jetsonorama features a photograph of JC, the child of his friends and patients, with a massive chunk of coal hanging like a black cloud over her head. The artist describes the complicated relationship of the Navajo and coal, where it is both source of employment and source of energy. In fact the coal in the photograph comes from the Kayenta mine, a Peabody Energy property still producing unlike Black Mesa. Jetsonorama explains that many households burn coal directly to heat their homes, as it is more cost effective than prohibitively expensive firewood, a practice that only serves to further the health crisis that the artist knows all too well through his medical practice.[29] Coal is now commonly known to contribute to climate change, but in Jetsonorama’s work it functions on multiple levels, as planetary disaster and as an extremely local, extremely complicated substance.

As noted, the location of Jetsonorama’s work along frequently travelled tourist routes, is important. But his use of Kayenta coal points to the fact that these massive mines share the same space as the wilderness preserved portions Dinétah. Berlo has emphasized that the Diné homeland is itself conceptualized as a hogan, based around the four sacred mountains: “European concepts such as wilderness and landscape make no sense in a system in which, at every level, one is within the safety of home.”[30] Jetsonorama’s placement of murals, from populated areas to the underpass of a coal train abutment, demonstrate the hypocrisy of a tourist economy built on the celebration, bordering worship, of certain spaces while neighboring environments are destroyed at very real human and ecological expense, ironically to power Western metropolises like Phoenix, Las Vegas and Los Angeles. His work, echoing Wilson’s, reveals all of the Navajo Nation to be home, with no place for arbitrary divisions between “preserved” and “destroyed” spaces. But like Wilson’s work, they move beyond depictions of the scourge of resource extraction to function as responses to this industry and its effects.

Michaela Rife is a Doctoral Student in Art History at the University of Toronto. She researches visual representations of land use in the American West across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She has presented widely on the intersections of artistic practice and land use in Canada and the United States. Her writing on Wyoming art and resource extraction can be found online at the Nevada Museum of Art’s Center for Art + Environment. In 2014 she curated the exhibition Dust on the Lens for Vancouver’s Or Gallery, which considered contemporary photographic responses to the American desert.

[1] Will Wilson, http://willwilson.photoshelter.com/#!/about

[2 ] Traci Brynne Voyles, Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 4-6; 139-140.

[3] Peter Iverson, Diné: A History of the Navajos (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002), 11.

[4] In fact as Monument Valley’s popularity as a tourist attraction coincided with its own postwar uranium boom. Voyles,Wastelanding, 105.

[5] Rebecca Solnit, Savage Dreams: A Journey into the Landscape Wars of the American West (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 273-276.

[6] Kim TallBear, “An Indigenous Reflection on Working Beyond the Human/Not Human,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21 (2015): 232-233.

[7] AIR 2 is located at the confluence of the Little Colorado and Colorado rivers, near Wilson’s family’s winter sheep camp. Recently the area has been the subject of the “Save the Confluence” campaign as developers look to build a resort complex known as the “Grand Canyon Escalade.” AIR 6 is located on the playas of southern New Mexico, the dry desert lakebeds that have been historically difficult for Anglo-Americans to appreciate aesthetically. See William L. Fox, Playa Works: The Myth of the Empty(Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2002).

[8] Martha A. Sandweiss, “Dry Light: Photographic Books and the Arid West,” in Perpetual Mirage: Photographic Narratives of the Desert West, ed. May Castleberry (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1996), 22.

[9] Klara B. Kelley, Navajo Land Use: An Ethnoarchaeological Study (Orlando: Academic Press, 1986), 7.

[10] Kelley, Navajo Land Use, 7.

[11] Iverson, Diné, 50.

[12] Kelley, Navajo Land Use, 7.

[13] Doug Brugge, Timothy Benally, and Ester Yazzie-Lewis, The Navajo People and Uranium Mining (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 2006), 28-29.

[14] Brugge, Benally, Yazzie-Lewis, The Navajo People and Uranium Mining, 29.

[15] Brugge, Benally, Yazzie-Lewis, The Navajo People and Uranium Mining, 30.

[16] Brugge, Benally, Yazzie-Lewis, The Navajo People and Uranium Mining, 105.

[17] Email to author. April 27, 2016.

[18] Voyles, Wastelanding, 214.

[19] Voyles, Wastelanding, 215.

[20] Janet Catherine Berlo and Jessica L. Horton, “Beyond the Mirror: Indigenous Ecologies and ‘New Materialisms’ in Contemporary Art”, Third Text 27 (January 2013): 25.

[21] Will Wilson, Email to author. April 27, 2016.

[22] Voyles, Wastelanding, 4.

[23] Giovanna Di Chiro, “Nature as Community: The Convergence of Environmental and Social Justice”, in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, ed. William Cronon (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1995): 300-301

[24] Di Chiro, “Nature as Community”, 311.

[25]Brooklyn Street Art, “Lola, Atomic Sheep Dog Drinking from the Uranium Mine per Jetsonorama,” July 14, 2015.http://www.brooklynstreetart.com/theblog/2015/07/14/lola-atomic-sheep-dog-drinking-from-the-uranium-mine-per-jetsonorama/#.Vxzo6T8i5Y4

[26] Karen Barad, “TransMaterialities: Trans*/Matter/Realities and Queer Politican Imaginings,” GLQ: Queer Inhumanisms. 21:2-3 (2015): 392.

[27] Voyles, Wastelanding, 9.

[28] Sherry L Smith and Brian Frehner, Indians & Energy: Exploitation and Opportunity in the American Southwest. (Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research, 2010), 12.

[29] “Jetsonorama for 350.org,” September 21, 2011. http://www.speakingloudandsayingnothing.blogspot.ca/2011_09_01_archive.html

[30] “Geographically the area is circumscribed by four sacred mountains: Mount Blanca in Colorado (east), Mount Taylor west of Albuquerque (south), the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff (the west), and Mount Hesperus in Colorado (the north), forming a parallelogram.” Janet Catherine Berlo, “Alberta Thomas, Navajo Pictorial Arts and Ecocrisis in Dinétah.” In Alan C Braddock and Cristoph Irmscher, eds. A Keener Perception: EcoCritical Studies in American Art History, 237-253. (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2009), 240.